The Story of WordPress - Part 1

1. Hello World

It was February, 2002 and Matt Mullenweg (matt) was in Houston, Texas, home from school. Sitting at his homemade PC, surrounded by posters of his favorite jazz musicians, he downloaded a copy of Movable Type, installed it on a web server, and published his first blog post.

I suppose it was just a matter of time before my egotist tendencies combined with my inherit (sic) geekiness to create some sort of blog. I’ve had an unhealthy amount of fun setting this up. This will be a nexus where I talk about and comment on things that interest me, like music, technology, politics, etc. etc.A few months later, and nearly five thousand miles away in Stockport, England, Mike Little (mikelittle) sat in the converted cellar that served as his home office. Surrounded by hundreds of books and CDs, he sat at a desk swamped by a 17" CRT monitor and spent his Sunday installing a free and open source blogging platform called b2. His first post is similar to Matt’s. Mike tells the world about his blogging platform and his plans for his blog: "There will either be nothing here," he wrote, "or a collection of random thoughts and links. Nothing too exciting. But then again I'm not an exciting person."

These two unremarkable blog posts, testing new system and welcome, are like hundreds of first blog posts before them -- a tentative first step, a software test, a pronouncement “I am here” with a promise of writing to come. What sets these two posts apart, is that they don’t just mark the beginning of two blogs, but a blogging platform that supports a community and an economy, that enables millions worldwide to write their “hello world” posts, too, and publish online.

Matt and Mike published their first posts at a time when more and more people were getting online and using the internet to express themselves. Blogging, while not quite in its infancy, was still maturing. A few years earlier, in 1998, there had only been a handful of weblogs. These early blogs were often curated collections of links accompanied by snarky or sarcastic commentary. These collections were web filters; the author surfed the web for readers who could then browse through links on weblogs they trusted. One of the earliest bloggers, Justin Hall, collected links to some of the darkest corners of the internet, but in addition to sharing the weird things he found, Hall poured his personal life online, and was a key figure in the transition from link log to personal diary.

As Rebecca Blood noted in 2000, blogs evolved from “a list of links with commentary and personal asides to a website...updated frequently, with new material posted at the top of the page.” It was this type of blog that brought Mike and Matt online, a format with established conventions that we’re familiar with today. Blogging software publishes content with the most recent post at the top of the page -- the first thing a visitor sees after landing on a site. This self-publishing premise has been a blogging feature from the earliest online diaries, to weblogs, to tumblogs, and even microblogging sites such as Twitter.

Many of the first bloggers were those already involved with the web: software developers like Dave Winer, designers like Jeffrey Zeldman, and technologists like Anil Dash. As a result, much of the earliest blog content was about the web and technology, interspersed with more diffuse thoughts and commentary about a blogger's life. With this tendency toward meta-commentary, bloggers wrote about the tools used to publish their blogs and the improvements they made to their sites. While blogging grew steadily, the community was still considered geeky and insular. Journalists disparaged bloggers, and rarely took their reporting seriously.

In 2001, blogging started to permeate the public consciousness. American political blogs became popular in the wake of the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Blogs such as Instapundit and The Daily Dish saw a massive surge in popularity. Andrew Sullivan, the blogger behind The Daily Dish, said that people didn't come to his blog just for news; "They were hungry for communication, for checking their gut against someone they had come to know, for emotional support and psychological bonding."

This was one of the first indications of the power of blogging -- it gave people a voice online, providing a platform where people could come together to grieve. In his book Say Everything: How Blogging Began, What It’s Becoming, and Why it Matters, Scott Rosenberg talks of how, despite the dot-com bubble burst, blogging increased in the last quarter of 2001. “Something strange and novel had landed on the doorstep,” Rosenberg writes in his introduction, “the latest monster baby from the Net. Newspapers and radio and cable news began to take note and tell people about it. That in turn sent more visitors to the bloggers’ sites, and inspired a whole new wave of bloggers to begin posting.” Since that time, blogging -- and later social media -- has played a pivotal role in politics, public life, and even revolutions.

As blogging evolved, so did blogging tools. Services like Geocities and Tripod allowed anyone to create a website, but these sites had little in common with the dynamic stream of content on a blog. The earliest blogs were manual, using HTML and FTP. On his blog, Justin Hall had a page titled Publish Yo' Self, which taught people how to write HTML and publish online, claiming that "HTML is easy as hell!" But writing and publishing HTML got in the way of the actual writing process; the dream was to create a tool for writing content and publishing it to the web with one click. Dave Winer, whose popular Scripting News was one of the earliest blogs, set up UserLand Software, which developed Frontier NewsPage, a tool that enabled people to create news-oriented websites like Scripting News.

In 1998, Open Diary, a community where people wrote diaries online and communicated with other diarists, launched. Then came LiveJournal, Xanga, and Pitas.com in 1999. In the same year, Pyra Labs launched Blogger, the tool often credited with popularizing blogging. Blogger automated publishing a blog to a web server: the user wrote their content, and Blogger uploaded the page to the server after each post.

Movable Type, the platform which, at one time, was one of WordPress' biggest competitors, launched in 2001. As with so many popular platforms, Moveable Type came about as a result of developers scratching their own itch. While Blogger was easy to use, it was limited in its functionality -- it lacked post titles, rich text editing, and categories. For reasons like these, Ben and Mena Trott created something different for Mena's blog. When they launched Movable Type in October 2001, it quickly became the most popular blogging platform, used by many of the major blogs at the time, including Instapundit, Wonkette, and Boing Boing. In many ways, Movable Type raised the bar for blogging platforms. It was not simply a publishing platform, but a publishing platform that people wanted to use. “I thought it was beautiful. I think in a lot of ways it foreshadowed the web 2.0, not the gradients and things, but the beauty and the white space," recalls Anil Dash. Now, “all of a sudden my blog posts had titles and I could have comments and I could archive things by month and I could do all manner of really interesting things. And all mostly with just HTML. Pretty much as easily as Blogger, but with just so much more power."

The tools got better. Soon publishing content wasn’t enough. Communities grew around different types of blogs. An author’s blog became a way for them to connect with people around the world. A blogger’s first, lone “hello world” quickly evolved into a series of posts that interlinked with other bloggers across the internet. Sidebars were embellished with “blogrolls,” lists of blogs that gave “link love” to favorite sites. Movable Type created Trackbacks to allow bloggers to track discussion on their articles across the internet.

It was into this arena that the nascent WordPress platform first said “hello world.” It did so quietly, not in Texas, nor in Stockport, but in the French island of Corsica. It appeared, first of all, not even as WordPress at all. In June 2001, months before Mike or Matt had even published their first blog posts, a developer in Corsica created his own blogging platform. He touted it as a "PHP+MySQL alternative to Blogger and Greymatter.” He called his PHP blogging platform b2.

2. The Only Blogger In Corsica

It was late 2000, and Michel Valdrighi (michelv) was writing a blog post in his small apartment above a bar in Corsica. The "only blogger in Corsica" used a creaking dial-up AOL connection that disconnected every thirty minutes. He shared his apartment with two cats, No Name and Gribouille, who perched on a windowsill overlooking a high drop.

Like many bloggers, Michel experimented with different web publishing platforms, and started out with HTML before moving to Blogger. But he discovered that Blogger wasn’t as fully-featured as he'd wanted. For example, it didn’t have a built-in comment system. This was at a time when bloggers could sign up for external commenting services that were often unreliable and unstable. Michel signed up for two different commenting services -- both of which disappeared, along with all of the comments and discussions. Blogger was also plagued by stability issues, and users sometimes joked that the platform was “sometimes up.”

Michel was learning the server-side scripting language PHP. Unlike a language like Perl, PHP is relatively easy to learn, making it a useful tool for people who want to start hacking on software. One of Michel’s first PHP projects was a Corsican-language dictionary: this experience taught him that he could use PHP to manipulate data, inspiring him to create his own blogging script. In June 2001, Michel started developing b2, fn-1 a "PHP+MySQL alternative to Blogger and Greymatter." He wrote:

Not much new ideas in it, but it will feature stuff like a built-in comment system, good users management (with complete profile etc), user-avatars (got piccies ?), multiple ways of archiving your blog (even post by post if you like to do a kind of journal) (sic).The installation will be easy, just edit a config file, upload everything and launch the install script. And there you go, but you’d like an admin control panel? It will be there, packed with options.

The PHP and MySQL combination was a good alternative to other contemporary blogging platforms. PHP is suited to the dynamic nature of a blog, in which an author regularly posts content and readers regularly return to read it. Movable Type used Perl, which rebuilt the page every time someone left a comment or edited the page, often making for slow page-load times. As a result, b2 was touted as an easy-to-use, speedy blogging tool. "You type something and hit 'blog this' and in the next second it's on your page(s)," boasts the sidebar of cafelog.com. "Pages are generated dynamically from the MySQL database, so no clumsy 'rebuilding' is involved. It also means faster search/display capabilities, and the ability to serve your news in different 'templates' without any hassle."

These features attracted Matt, Mike, and many other bloggers. But Michel admits to being a novice developer, learning PHP and MySQL while building the precursor to one of the most widely-used blogging and CMS platforms in use today. He recalls that as a fledgling PHP developer, he didn’t always do things correctly:

When you look at WordPress' code and think 'Wow, that's weird, why did they do that this way?', well often that's because they kept doing things the way they were done in b2, and I sucked at PHP.

Like other early blog software developers, Michel was "scratching his own itch" -- a familiar phrase in free software development. This means creating the tools you need, whether that's a blogging platform, a text editor, or an operating system. In his book, The Cathedral and the Bazaar, Eric Raymond writes, “every good work of software starts by scratching a developer's personal itch.” If a developer has a problem, she can write software to solve that problem, and then distribute it so that others can use it too. Many blogging platforms, including Blogger, b2, Moveable Type, and WordPress, started life in this way.

By being both the software developer and its user, the developer knows whether the tools she creates meet her real needs. When developers write code, they use it just as any user would. They know what works and what doesn't. Scratching an itch gives the developer a closer relationship with the software's users -- it’s grass-roots development that's bottom-up as opposed to top-down.

Michel wanted a blogging tool, not a CMS, so early b2 features were focused on creating a frictionless way to blog. Early enhancements made writing easier. For example, AutoBR was included to add a <br/> tag to create a new line every time a writer hit enter. As Michel’s, and later the community’s needs changed, improvements included a basic templating system, an options page, archives, an option to allow users to set their own timezone, and comments.

Michel believed that any layperson should be able to easily publish on their blog with b2. This "making software easy for everyone" ideal permeated the b2 community and would eventually become a core ideal in WordPress’ own philosophy.

By the end of June 2001, Michel was ready to say goodbye to Blogger and move his blog to b2. His blog was the first website to run on the code that would become WordPress, grandfather to millions of websites and blogs. A few days later, Michel set up a website called cafelog.com, and released the first version of b2. The software was quickly picked up. The second site running b2, the personal weblog of a schoolboy named Russell, was published in July 2001.

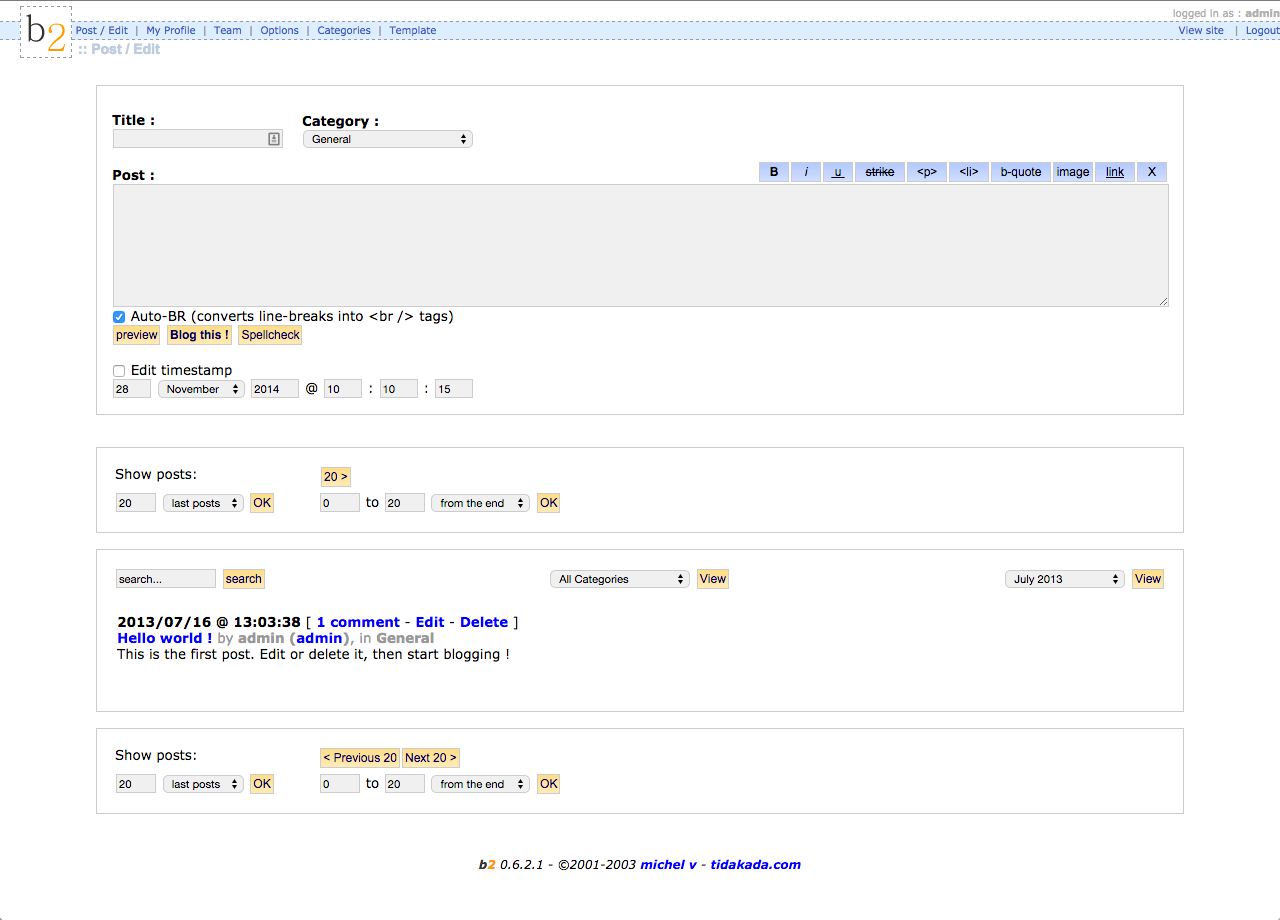

The b2 user interface

Development didn’t always go smoothly, although solving problems inevitably led to platform refinements. Brigitte Eaton, who ran a site called Eatonweb, was the first prominent b2 user. Eatonweb was a hand-maintained list of blogs, a go-to place for discovering new blogs until the number of blogs exploded and hand-maintained lists became untenable. It was superseded by the ubiquitous blogroll and services like Technorati, which started ranking blogs according to incoming links. Brigitte Eaton published regularly, and when she imported her blog into b2 she found that the more posts she added, the slower the blog loaded. This was because Michel didn't know how to write code for retrieving months of content from the archives. His code parsed every post on the blog to query whether the post had changed and then displayed it. For blogs with many posts, this meant a huge server workload, which quickly slowed the website. Solving this problem meant improvements for all b2 users.

Although b2 did not have an established developer infrastructure, it was open for contributions. The first major code contribution to the project was pingback functionality, from developer Axis Thoreau, who went by the handle Mort. fn-2 Movable Type had a similar linkback feature called trackback; Michel added a version of it to b2. Trackback is a ping sent from the original author’s site to a site they reference with a link. Unlike pingbacks, trackbacks are manual so the original author has to choose to send the trackback, and can edit the excerpt sent. Trackbacks are much more susceptible to spam than pingbacks; fn-3 whereas pingbacks ping back to the original site to verify that it is not spam, trackbacks do not carry out the same checks.

With users and developers frequenting b2's forums, a community quickly formed. The forums were a haven for people who needed help with the software. The most popular were the installation, templating, and how-to discussion forums, but there were also forums just for general chatter about the software and about blogging. Developers helped each other out with hacks for b2, and it was on the forums that the early WordPress developers first met.

Outside the b2 community, the software was criticized. Michel's lack of coding experience showed, especially to experienced developers. Blogger Jim Reverend wrote a post titled, "Cafelog: A Look at Bad Code." In it, Jim bemoans poor code quality in publicly released software -- particularly b2 -- and criticizes the software for its lack of features fn-4 and poor coding practices.

Michel's lack of PHP experience meant that he wrote inefficient code and used techniques counter-intuitive to a more experienced coder. Rather than taking a modular approach to solve a logic problem, the code grew organically, written as Michel thought about it -- a sort of stream-of-consciousness approach to coding. Code wasn't so much a tool to solve a problem, but a tool to get the newest feature on the screen. This created multiple code interdependencies, which caused problems for developers new to the project. A line of code would change and break something that appeared unrelated. For Reverend, this type of "dirty code" was unforgivable. "What I do have a problem with," he wrote, "is my inability to use his code (without extensive reading and rewriting) to implement my own features." Writing extensible code is a fundamental principle of free software. If code is written in a stream-of-consciousness fashion outside best practices, it becomes difficult for other developers to extend.

It wasn't all bad. In a follow-up article, Reverend concedes that there are benefits to poorly written code:

While programmers like myself start convulsing when we have to wade through such code, less experienced programmers actually like it, because it is easier for them to work with. Because the "template functions" are in the global namespace, they work anywhere. Because the data returned by the database is in a global variable, you don’t have to use any tricks to get at it. It makes extending, enhancing, and modifying the code easier for newbies.Michel's inexperience gave the code a level of simplicity that made it easy for other novice developers to understand. "In a way it was beautiful because it was so simple," says developer Alex King, (alexkingorg). "It wasn't elegant but it was straightforward and accessible. For someone who didn't have a lot of development experience coming in -- like me -- it was very comfortable understanding what was going on."

The article also highlights something important: people liked using b2. With b2 they could publish without hassle. "If you are a user of this product," writes Reverend, "please don’t tell me about how cool it is, or about how well it works. If you read a site powered by this engine, please don’t tell me about how easy you find it to use."

But people did find it easy to use. To users, it didn't matter what was going on under the hood. It may have had its problems, but it was a friction-free way to get content online. Where users went, developers followed; even better if those users were novice developers themselves, fumbling at the edges of PHP, learning what they could do with code, which new features they could add to their website and share with other users. Even in these very early days, a schism started to open between developer-focused development and user-focused development. On the one hand, there was a focus on logical, beautifully written code, and on the other, a focus on features users wanted.

Despite having distributed b2, Michel hesistated over his choice of license. The free software movement was relatively young, and many large projects had their own licensing terms (such as Apache, PHP, and X.Org). Until he chose a license, Michel distributed b2 with his copyright.

On the b2 blog, you can follow the events leading to b2’s distribution with a GPL license. In August 2001, Michel made a brief statement on cafelog.com, telling people that they could use his code provided he was given credit for it, stating explicitly that "b2 isn't released under the GPL yet." People were taking notice of b2 and some passed it off as their own. In October 2001, a Norwegian agency claimed to own the copyright to b2 and Michel was forced to contact the Norwegian copyright agency. In the discussion around this incident, Michel made a statement that came as close to a license as he'd had so far:

You can use b2 for free, even if your site is of commercial nature. You're welcomed to buy me items from my Amazon.com wishlist if you're going to make much money from your b2-powered site or if you just like b2.You can edit b2's source code.

You can re-distribute a modified or original version of b2. In no way your modifications make you author or co-author of the modified version, I'll remain b2's sole author and copyright holder. (sic)

Any help is welcomed. Feel free to submit fixes and enhancements, they might get in b2's code and your name or email address will be there as credit in the source code.

I guess this makes a b2 license for now.

Michel released b2 under this slapdash license until he realized that b2 needed an official license and started looking in earnest. It was important to Michel that b2 remain free, even if he stopped working on the project. He also wanted his code to remain free if other developers took it and used it in their own project. He recalls now that "at the end of that elimination process, GPL remained. It helped that there were already some projects using it, as I didn't want the code to end up abandoned and forgotten because of the choice of an exotic license."

Michel's choice of license was prescient. Under a GPL license, software can be forked, modified, and redistributed. If development stops (as it did with b2), the ability to fork, modify, and redistribute can prevent software from becoming vaporware.

All was going well until May, 2002 when Michel lost his job. In the months following, he continued to develop b2, but he wrestled with depression and health issues. His electricity was cut off, he moved, and struggled to find a job. With so much going on in his life, Michel eventually disappeared. He posted about spam in December, 2002 but didn’t post on his personal blog in 2003.

The users of b2 had no lead developer. There was no one to steer the project, fix bugs, apply patches, or add new features. People were concerned about Michel -- they liked him and were worried about what had happened to him. In March 2003, a thread on cafelog.com discussed Michel’s whereabouts. Michel’s sister, Senia, posted that he was well and that he was looking for a job, and promised to ask him to connect to IRC and MSN. The responses to Senia were mixed.

One commenter said:

Please pass on to Michel that not only has he created a really nice piece of software, but he has also inadvertently built a community […] of people, a sort of commonwealth on the blogosphere. I don't know him the slightest bit, but I wish him well and hope that any soul searching or vision quest (or vision exodus?!) he has embarked on helps him find what he needs. Yet also allows him to tie up any loose ends that he leaves behind.Others had concerns about their own projects:

Anyone heard from Michel yet? His last post was 6 weeks ago. I want to install and promote b2 in two projects (one affiliated with a UN women's project).. but I am nervous about doing so if there will be no developer support available. I am sure he knows that b2 is including (sic) in the Fantastico auto-installer bundled with the cPanel virtual hosting tool. I want to write an blogging article for hosting clients. Michel? You going to be around?Michel never went back to b2 with the same gusto with which he had started. Eventually, the stagnation made the software unusable. Software needs to be maintained -- bugs need to be fixed, security issues patched, new features need to be added. Blogging software needs to evolve with a fast-moving internet. It wasn’t just the software that was on the verge of becoming vaporware -- the community was adrift too. In the free software world, the community is as important as the software. The community is the garden in which the software grows and matures. Community members submit patches, fix issues, support users, and write documentation to help a free software project flourish. But every project needs a person, or group of people, to commit patches, create new features, and steer the project. When the lead developer disappears without a trace, community members can play around the edges, help out with support and hacks, but, without someone to step up and take the lead's place, the community dissolves. People move on to other projects, or start their own. After all, if the person who owns the project shows no commitment, how can commitment be expected from anyone else?

But the GPL license meant that neither the code nor the community had to disappear. Developers -- familiar names from the b2 community forums -- forked the software. While b2 itself did not continue, it was the platform that connected Mike and Matt, and the software that would provide the foundation for WordPress. With its simple PHP and focus on usability and ease of use, b2 contained the rudimentary ideals that would form the heart of WordPress. But first, the software had to be forked, and, as bloggers are wont to do, they took to their blogs to do it.

3. The Blogging Software Dilemma

The internet brings people from different backgrounds, countries, and cultures together around shared interests. On a small corner of the internet, b2 was forming one such community. People supported one another because they were interested in two things: blogging and blogging software.

The founders of WordPress were among those drawn into the b2 community. They were from very different backgrounds, but free software formed their common ground. In Houston, Matt Mullenweg wrote about politics, economics, technology, and his passions for jazz music and photography. Mike Little, from Stockport, wrote about blogging technology, the books he read, and his family.

Matt and Mike had very different entries into computing: Matt's father was a computer programmer, and Matt started tinkering with computers at an early age. Mike, who was 22 years older than Matt, had his first computer experiences at school cut short when a teacher caught him and his friends smoking in the paper room.

A shared passion for music drew them both deeper into programming. Mike was involved in the Manchester music scene in the 1980s, working at a record shop and handing out ‘zines for nightclub manager and record label owner Tony Wilson. He lived with a local glam rock band, and it was through the band that computing came back into his life. The lead singer thought it would be cool to have stacks of televisions with graphics on either side of the stage. Mike borrowed a ZX Spectrum and used a couple of programs from computing magazines: one of them bounced objects around the screen, the second created 3D text. He hacked on them until the words he wanted bounced around a screen, but the plan fell flat when they couldn’t figure out how to output the program to multiple screens at the same time. Despite not being a total success, this incident further cemented his reputation for being the go-to guy for all things computing and music.

By the time he arrived at b2, Mike had nearly twenty years of programming experience. That first faltering step with the ZX Spectrum had started a love affair with coding, which took him on a route through Basic, 6502 Assembler, Pascal, and C. He learned PHP during the transition between PHP versions one and two.

In Houston, Matt set up his first business while studying at the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts (HSPVA). While Mike’s music passion was post-punk, for Matt it was jazz. He built computers and websites for his music teachers, including his saxophone teacher, David Caceres. He also used the internet to connect other music fans in the Houston area, setting up a forum on David Caceres' website. Matt used the forum software phpBB -- his first taste of using PHP -- to create a dynamic website.

With experience in PHP, b2 was the perfect platform for Matt and Mike to publish their content and to let their hacker tendencies loose. Matt experimented with other platforms, including Movable Type, but at the time, it didn’t have pingbacks and comments were in pop-ups, as opposed to being inline. Movable Type was written in Perl with a DBD database, which meant that customizing Movable Type was more difficult than a PHP platform.

PHP and MySQL allowed Mike and Matt to scratch their blogging and hacking itches. They hacked on their websites and customized as they saw fit, and shared those hacks and improvements with the community. Their first discussion was around the gallery software Matt used on his blog. Other developers had their own itches to scratch: developers were talking about building their own platforms; others, in the absence of Michel, were considering a fork.

As free software licensed under the GPL, it meant anyone could fork b2 and use it, provided their fork retained the GPL license. By early 2003, it was clear that Michel would not be back. No one was maintaining b2 or fixing security issues. The blogging software at the core of the growing community was no longer evolving. The web, and blogging, was moving forward, but b2 had lost its driving force. In France, François Planque forked b2 to create b2evolution. The lack of b2 development frustrated François and he wanted to continue to develop b2 for his own needs.

In Cork, on the west coast of Ireland, Donncha Ó Caoimh, (donncha), forked b2 to create b2++, a multi-user blog platform. Donncha discovered b2 while searching for a platform to create a blog network for his Linux user group. He found b2 small, basic, and easy to modify. However, he made major modifications to create blogs.linux.ie. The templating system for b2++ used Smarty, which separated code and presentation, making it easier for users on the network to change their site's design. Donncha didn't consider b2++ a fork of b2. "A fork gives the impression that it was competing -- it wasn't competing because most of what it did was add multi-user aspects to the project." While b2 was a platform aimed at individual bloggers, everything that Donncha did in b2++ created a better multi-user environment.

On his blog, Matt wrote a post called "The Blogging Software Dilemma," in which he proposes forking b2. He wrote:

b2/cafelog is GPL, which means that I could use the existing codebase to create a fork, integrating all the cool stuff that Michel would be working on right now if only he was around. The work would never be lost, as if I fell of the face of the planet a year from now, whatever code I made would be free to the world, and if someone else wanted to pick it up they could. I've decided that this (sic) the course of action I'd like to go in, now all I need is a name. What should it do? Well, it would be nice to have the flexibility of Movable Type, the parsing of Textpattern, the hackability of b2, and the ease of setup of Blogger. Someday, right?The next day, from Stockport, Mike Little responded:

If you're serious about forking b2 I would be interested in contributing. I'm sure there are one or two others in the community who would be too. Perhaps a post to the b2 forum, suggesting a fork would be a good starting point.Today, the post that started WordPress gets a lot of traffic when people link to it on the software’s anniversary. But for more than a year, that post sat there with just one comment, a marker of the very early days of the project, when for a few months, just Matt and Mike, in their homes at opposite sides of the Atlantic, started creating WordPress. At the beginning, it was just two developers working on a small script to make their blogs better. By forking b2, they could continue to use the software, develop it for their own needs, and scratch their own itches. At that moment, in a small pocket of the internet, the right people connected. They may have been from completely different backgrounds, but a shared love of creating tools, playing with code, and publishing online brought them together.

On April 1, 2003, Matt created a new branch of b2 on SourceForge, and, with the name coined by his friend Christine Tremoulet, called it WordPress.

fn-1 The name b2 is a combination of the word “blog” and “Song 2” by the British band Blur, which Michel had been listening to regularly at that time. He combined them to make “blog2,” then “blogger2,” until he arrived at b2. b2 was also known as Cafelog, which was the name Michel had planned to give to the 1.0 series as no b2 domains were available, and the name was too short for a project on SourceForge.

fn-2 Pingback is a linkback method which authors use to request notifications when someone links to their website. An author writes a post on their blog that links to a post elsewhere. The original site sends an XML-RPC request and when the mentioned site receives the notification signal, it goes back to the original site to check for the link. If it exists, then the pingback is recorded. A blogging system can then automatically publish a list of links in the comment section of the post, or wherever the developer chooses to place it.

fn-3 Spam pings are pings sent from spam blogs to get links on other websites.

fn-4 Particular problems that the article calls out include the fact that b2 didn't cache calls to the database. So when there was a new visit from a user, the page had to be loaded from the database and server, slowing the website. The article also criticized the lack of flexibility in the templating system and the absence of cruft-free URLs (known in WordPress lingo now as "pretty permalinks").