The Story of WordPress - Part 3

You are reading the third part of the series, find the whole series at series/wpbook.

12. Themes

Templating was the next area ripe for improvement -- users could extend their blog and have it in their own language, but there wasn't yet an easy way to change their site’s design. Even in the b2 forums, many support questions were about changing a website’s design. A blog is a visual representation of the author, their tastes, and their interests -- a blog is a home on the internet, and, just as with any home, owners decorate it according to their tastes. To change the look of a b2 or early WordPress blog, the user had to create a CSS stylesheet. This changed the colors and layout on the front end. However, it didn’t offer any real flexibility in site design; a robust templating system was needed. Michel had looked into creating a templating system for b2, but it was not until the transition between WordPress 1.2 and 1.5 that WordPress got its theme system.

A lot of research went into finding the best approach to templating. Smarty templates came up again and again. Smarty is a PHP templating system that allows the user to change the front end independently from the back end. The user can change their site's design without having to worry about the rest of the application. There are a number of posts on the WordPress.org development blog discussing Smarty's merits. Donncha even imported it to the repository (his first commit to the project). But, despite sharing PHP with WordPress, Smarty had a difficult syntax to learn. In the end, it was rejected for being too complicated. What WordPress needed was a system as easy to use as the software itself.

While templating system discussions continued, WordPress users got creative with CSS stylesheets. To make switching designs easy, Alex King wrote a CSS Style Switcher hack, which came with three CSS stylesheets. Not everyone who had a WordPress blog wanted to create their own stylesheet, and many didn’t know how. Users needed a pool of stylesheets to choose from. To grow the number of stylesheets available, Alex ran a WordPress CSS Style competition. Prizes, donated by members of the community, were offered for the top three stylesheets; 35, and $10, respectively.

Creating a resource similar to the popular CSS Zen Garden was the secondary aim of the stylesheet competition. Just as the CSS Zen Garden showed off CSS' flexibility, a CSS stylesheet repository would show off WordPress' flexibility.

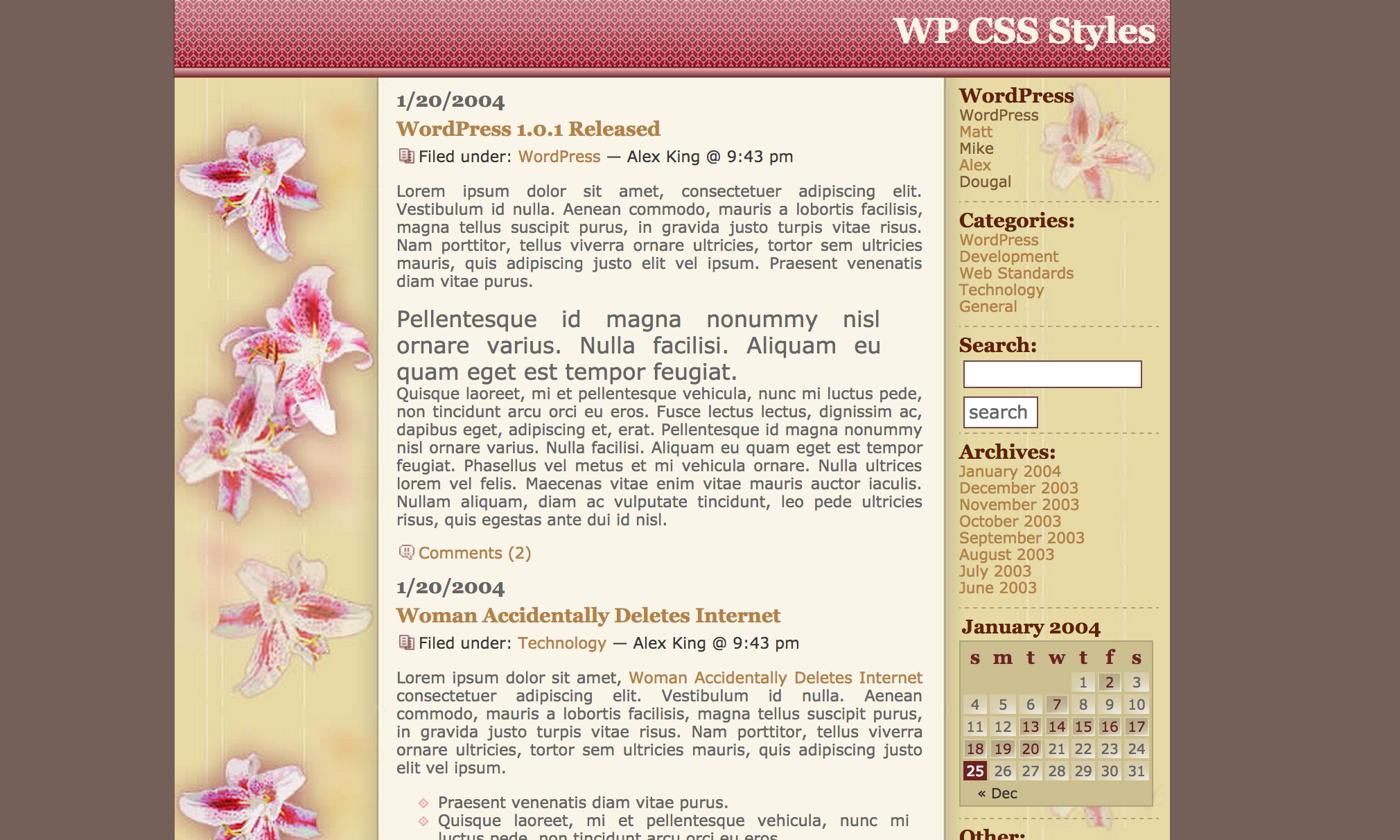

The competition created buzz in the community. In total, there were 38 submissions. Naoko Takano won the first competition with her entry, Pink Lillies:

The Pink Lillies design, by Naoko Takano

The competition successfully widened the pool of available stylesheets, increasing the number from seven to 45. On his website, Alex launched a style browser to allow visitors to view the different stylesheets. The competition ran again in 2005, this time receiving more than a hundred submissions.

By the second competition, the theme system was in place and designers had more tools to design and build their theme. Alex’s experience in the second competition, however, foreshadowed problems that would dog the community in later years. In hosting 138 themes on his site, Alex had to review all of the code to make sure there was nothing malicious, and to ensure that each theme used coding best practices. He decided not to host the competition again in 2006 due to the sheer amount of work it required. WordPress’ growth meant there would be even more submissions, far too many for one person to review. This problem persisted as the project grew: how does one balance a low barrier to entry with achieving good code quality, particularly in third-party plugins and themes?

Still, the 2005 competition showed off the flexibility of the brand new theme system, which appeared in February 2005, in WordPress 1.5. [fn^1] In the end, the theme system was built using PHP, which is a templating language itself, after all. Using a PHP template tag system was fast and easy, particularly for WordPress developers and designers who were learning PHP. It was "cheap and easy, and well-known and portable," says Ryan. The theme system breaks a theme down into its component parts -- header, footer, and sidebar, for example. Each part is an individual file that a designer can customize. Designers use template tags to call different elements to display on the front end. This bundle of files is a WordPress theme. A native WordPress theme system, as opposed to a templating system such as Smarty, meant that designers could design and build themes without learning an entirely new syntax.

Bundled with WordPress 1.5 was a new default theme -- an adapted version of Michael Heilemann’s Kubrick. While some welcomed the new theme, others were unhappy that it was chosen:

The Kubrick Theme, which was WordPress' default theme until 2010

One of the problems with Kubrick was that it contained images; if a user wanted to change their theme they had to use an external image editor. Some felt that users should not be expected to download additional software just to change their site’s design. Others thought Kubrick too complex; it had .htaccess issues, and that other (better) default theme choices existed. The thread on the forums reached five pages with substantial flaming.

These types of fires ignite quickly in bazaar-style development. They can get out of hand as people take their opinions to blogs and social media. As with many debates in free software communities, the Kubrick debate burned ferociously for a short time before fizzling out. But the brief outbreak portended later debates about WordPress themes. There’s something about themes that ignites passions more than other aspects of WordPress.

Still, by the release of WordPress 1.5, the software had two elements that define the project and the community: themes and plugins. These two improvements transformed WordPress from stand-alone software into an extensible platform. Extensibility creates the right conditions for an ecosystem to flourish. If a product is solid and attracts users, then developers will follow, extending the software and building tools for it. The theme and plugin systems made this possible, in both features and design.

[fn^1] WordPress versions were skipped between 1.2 and 1.5. This was due to the length of time between the two releases.

13. Development in a Funnel

Following WordPress 1.5, the software development process changed, precipitated by a version control system shift from CVS to a more modern version control system, Subversion (SVN). fn-1 The most active contributors at that time were Ryan and Matt, and when the move was made, none of the other original developers had their commit access renewed.

A committer is someone who can use the commit command to make changes to the group’s central repository. The number of people who can do this on a project varies, with projects deciding on the number of committers depending on their own structure and philosophies. The question of who should have commit access to the WordPress repository comes up again and again. There are regular threads requesting that more people be given commit access.

The move from CVS to Subversion marked a long period in which WordPress development operated through a funnel. Contributors created a patch, uploaded it to Mosquito (and later trac), fn-2 and it was reviewed by one of the committers who committed the code to the main repository. Over time, the funnel narrowed as Matt’s focus went elsewhere and Ryan drove development. This "funnel" development style has advantages and disadvantages, and it was frequently the subject of discussion among the community, particularly on wp-hackers. The advantage of a funnelling process is that disagreements about code happen on the mailing list, before a change lands in the repository. The disadvantage is that one person has to review every patch, which frustrates developers waiting for their patches to be committed.

As WordPress began to take shape as a recognized free software project, with a defined development process and proper developer infrastructure, Ryan’s previous experience guided many of these changes. WordPress differed in that Linux has only one committer -- project founder Linus Torvalds -- whereas WordPress had two in Matt and Ryan. Over the years this opened up to more and more committers. The other difference is that Linux has "maintainers" who maintain different subsystems before pushing patches upstream. This means that Torvalds doesn’t review the thousands of patches that go into the kernel. He reviews a fraction of them and delegates review to trusted subsystem maintainers. Although WordPress in the future would move toward component maintainers, it never followed Linux in this manner.

There are a number of reasons that people request commit access: to speed up development, to prevent situations in which patches wait months for a review, to acknowledge the contributions of project regulars, to create a more egalitarian project structure. Adding a new committer to a project became a major decision and the project’s approach changed dramatically from the wild west days of coding in WordPress 0.7. When the project started, anyone who demonstrated some technical expertise and minimal dedication got commit access. All of those developers could commit code to the repository whenever they wanted. But as the project and the number of users grew, it became more important to have some sort of filtering mechanism. A committer is the filter through which the code is passed. When someone is given commit access to the repository, it demonstrates a level of trust. It signifies that a contributor is trusted to know which code should make it into WordPress.

Karl Fogel describes committers as “the only formally distinct class of people found in all open source projects.” “Committers are an unavoidable concession to discrimination in a system which is otherwise as non-discriminatory as possible,” he writes. As much as one tries to maintain that commit is a functional role, commit access is a symbol of trust, both in terms of coding skills and in a person’s adherence to the project’s core beliefs and ethos. A power dynamic exists between those who have commit access and those who don’t.

Committers provide quality control. To decide who to give commit access to, a project maintainer has to first find people who not only write good code, but who are good at reviewing other people’s code. This means being good at recognizing places in which code can be improved and providing constructive feedback. But there are other social skills that go along with being a committer. For one, the person needs to adhere to a project’s ideals. Within WordPress, this means being fully committed to the project’s user-first approach. Committers also need to “play well in the sandbox.” Someone may write flawless code, but if they are unable to work with others they aren’t going to make a wonderful committer. It’s important to make good choices about who gets commit access because once it's been given, it's difficult to take away.

In an attempt to avoid an “us and them” mentality in which committers have higher status than everyone else, the WordPress project had only two committers. This meant that everyone was subject to the same review process and the same rules. Opening it up to more people may have created dissatisfaction among those who didn’t have commit access. But by not opening it up at all, developers who felt that they could never progress within the current project structure became frustrated. So few committers in a growing project also meant a mounting number of patches that languished on trac as they awaited review.

There is a perennial tug-of-war between those who contribute to the project and those who maintain it, and even among the project leaders themselves. Who gets commit access and for how long? What sort of status is attached to commit? Should only lead developers be committers? What is a "lead developer" anyway? Over the coming years these questions play out at various stages in the project’s development.

14. A New Logo

As development progressed, WordPress’ design and branding took shape. Some of the first lengthy discussions about WordPress' look and feel happened on the wp-design mailing list. This was a private mailing list of designers and developers interested in crafting WordPress’ aesthetic. Michael Heilemann (michael), Khaled Abou Alfa (khaled), Joen Asmussen (joen), Chris Davis (chrisjdavis), Joshua Sigar (alphaoide), and Matt composed the main group.

The first focused design discussion was about WordPress’ logo. Matt designed the original logo; it was simply the word "WordPress" in the Dante font:

The original WordPress logo.

Since the project was so small, community members had fun on the homepage, riffing on the logo with versions for seasonal holidays, birthdays, and other events.

Logos that were created for WordPress.org for special occasions.

Eventually, WordPress needed a professional logo. Usage was growing and WordPress needed a logo that properly represented it. As a free software project, the community was the first place to look for a logo. Community suggestions were solicited. A mixed set of results came back, which were shared with the wp-design group for feedback.

The first suggestions were from Andreas Kwiatkowski:

WordPress logo suggestions from Andreas Kwiatkowski.

A second batch came from Denis Radenkovic:

WordPress logo suggestions from Denis Radenkovic.

Logo feedback was mostly lukewarm, though some of the designers liked Radenkovic's heart logos, describing them as "instantly recognizable."

The heart logo was iterated on, with another version posted to the design mailing list:

Joen Asmussen's iteration of the heart logo.

A version of the admin screen with it in situ was produced.

Joen Asmussen's admin design with the heart logo in situ.

Community members weren't the only ones tackling the logo. In March, Matt met Jason Santa Maria at South by South West and asked him to try redesigning the WordPress logo. They shared ideas about what they thought the logo should be: "the things that kept coming up were not only the idea of publishing but the idea of having a personal journal and a personal thing that might have some sort of tactile overtones," Jason says. "We were making links to things like letterpress and journaling and any sort of older representations of what it meant to publish something in a physical form." In April 2005, some of the early versions were shared with the wp-design group:

The first logo ideas sketched by Jason Santa Maria.

There were a number of responses from the designers on the mailing list: "a little too aristocratic" was one of the comments. The designers felt that Denis Radenkovic's design was more in line with WordPress' brand.

More designs were posted to the group:

Further iterations on the logo design from Jason Santa Maria.

The members of the mailing list didn’t seem to agree on WordPress’ aesthetic. On one hand, there were people who felt that the logo should represent warmth and community, and on the other hand, something classic and elegant. To reach a consensus, discussions happened offline. Khaled reported back:

WordPress is meant to be the Jaguar or Aston Martin of Blogging tools. [...] that line sets the stage for what the design of the branding should be. Elegance, polished, and impecably [sic] designed is where we should be aiming.The logo was finally decided on May 15th, when Matt sent an email to the mailing list with the subject "I think this is it." Matt's message contained just one image:

The final design for the WordPress logo.

The major change to the logo, other than the new typeface, was the mark. The creation of a mark gave WordPress a stand-alone element of the logo which, over time, would be recognizable even without the word beside it. This could and would be used in icons, branding, and t-shirts. It’s become instantly recognizable, helped by its appearance on WordCamp t-shirts the world over.

15. WordPress Incorporated

As the number of people using WordPress grew steadily, more and more needed to get done. Matt took a job at CNET, which allowed him to work on WordPress alongside his day job. Ryan was working at Cisco, often 60 or 80 hours a week; he would come home to work on his hobby, WordPress. Apart from time spent on the project, there are all sorts of associated costs that come with running a growing project. Server costs, for example, that increase as the project's popularity grows.

At the start of March 2005, WordPress 1.5 had seen 50,000 downloads. Just three weeks later, the number doubled to 100,000. To celebrate the landmark, there was a 100K party in San Francisco. On March 22, a group of WordPressers got together at the Odeon Bar in San Francisco.

Jonas Luster (jluster) was at the party. Jonas was an employee at Collabnet, the company behind Subversion. He and Matt had been talking about what a company built around free software should look like. Matt had an idea for an organization called Automattic: an umbrella company that would include several WordPress organizations. The first of these was WordPress Incorporated. At the party, Matt asked Jonas if he'd like to be involved. Jonas said yes.

Shortly afterward, Matt jumped on stage to announce WordPress Inc. -- with Jonas Luster as employee number one. By the following morning, a couple of blogs had covered the announcement. A few days later, Matt went on holiday leaving WordPress' very first employee in charge.

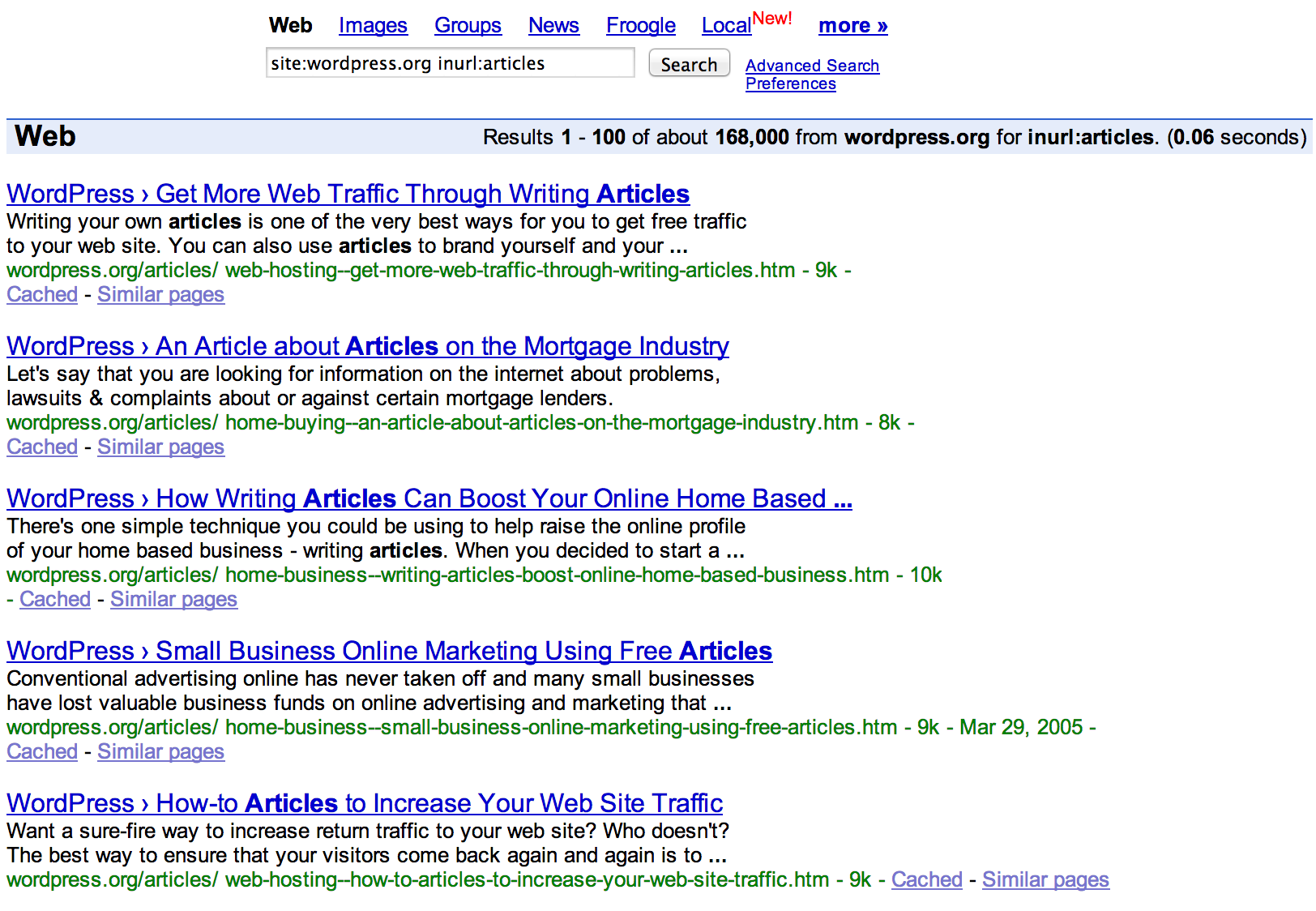

Even as the party was going on, trouble was brewing. In February, a user posted to the WordPress.org support forums asking about hundreds of articles hosted at wordpress.org/articles/. The articles were about everything from credit and healthcare to web hosting. The thread was closed by a forum moderator. Blogger Andy Baio discovered the thread. He contacted Matt to ask about what was going on.

The Google search results that show the articles hosted on WordPress.org. (Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.)

Matt explained to Andy that he was being paid by a company called Hot Nacho to host the articles on WordPress.org and that he was using the money to cover WordPress' costs. "The /articles thing isn't something I want to do long-term," he told Andy, "but if it can help bootstrap something nice for the community, I'm willing to let it run for a little while." In addition to responding to Andy, Matt re-opened the support forum thread and left a response:

The content in /articles is essentially advertising by a third party that we host for a flat fee. I'm not sure if we're going to continue it much longer, but we're committed to this month at least, it was basically an experiment. However around the beginning of Feburary [sic] donations were going down as expenses were ramping up, so it seemed like a good way to cover everything. The adsense on those pages is not ours and I have no idea what they get on it, we just get a flat fee. The money is used just like donations but more specifically it's been going to the business/trademark expenses so it's not entirely out of my pocket anymore.

On March 30, while Matt was in Italy, Andy published an article about it on his blog. The reaction from bloggers was bad: no matter what Matt's intentions, people saw the articles as a shady SEO tactic. A free software project should know better than to work with article spammers. Not only was WordPress.org hosting the spammy articles, CSS had been used to cloak them. If everything was above board, why not do it out in the open? The articles also had an influence on WordPress.org’s hosts, TextDrive, who hosted WordPress for free on a server along with apps such as Ruby on Rails. Their servers were overloaded with hits from the links in the Hot Nacho articles.

With Matt out of town, Jonas dealt with the fallout from Andy Baio's article on Waxy.org. It wasn't clear where the line between WordPress.org and WordPress Inc. lay, but Jonas was the only official-sounding person. He fielded the tech community's ire and spent the next few days putting out fires. Jonas posted on his blog asking for calm, and that Matt be given the benefit of the doubt.

The Hot Nacho articles were perceived as the first move by WordPress Inc. to make money -- an indication that Matt and Jonas were't going to monetize WordPress in an ethical manner. Jonas stressed that the articles had nothing to do with WordPress Inc., but since it wasn’t clear at that time what WordPress Inc. actually was, people naturally lumped them together. By the next day, Andy had updated his post to report that WordPress' PageRank had dropped to 0/0. WordPress.org had been removed from Google's search engine results.

The story escalated as major tech resources like The Register, Slashdot, and Ars Technica picked it up. On March 31, Matt posted briefly on his blog to say that he had just learned of what had happened and that he would get online to address the questions as soon as possible. The comments are littered with messages of support from people who would later be central to the project and even from Matt's rival. Matt also received support on WordPress' support forums. On April 1, Matt issued a full response. In it, Matt explains that he was struggling to find a way to support the free software project, and that he felt that his options were limited:

To thrive as an independent project WordPress needs to be self-sufficient. There are several avenues this could go, all of which I've given a lot of thought to. One route that would be very easy to go in today's environment is to take VC funding for a few million and build a big company, fast. Another way would be to be absorbed by an already big company. I don't think either is the best route for the long-term health of the community. (None of these are hypothetical, they've all come up before.) There are a number of things the software could do to nag people for donations, but I'm very hesitant to do anything that degrades the user experience. Finally we could use the blessing and burden of the traffic to wordpress.org to create a sustainable stream of income that can fund WP activities.

Hosting the articles on WordPress.org attempted to mitigate the free software project's costs. For many people, Matt's response satisfied their concerns and questions. But for others, it wasn't enough. If a free software project has to resort to turning its highly ranking website into a link farm, what is the future viability of that project? Aren’t there other ways to support it? Matt had been at the web spam summit in February, which had specifically addressed "comment spam, link spam, TrackBack spam, tag spam, and fake weblogs." Hadn't he, at that point, realized that there might be something dubious?

As with most storms on the internet, once the articles were removed and Matt had apologized, the anger subsided. It did, however, have a lasting influence. The experience changed Matt's thinking about spam. Instead of viewing it purely as something that appears in an email inbox, he now saw it as web spam, which can quickly pollute the web. This influenced his thinking when developing Akismet, Automattic's anti-spam plugin. And while Matt had learned a harsh lesson about ethical ways to make money on the web, it would return to haunt him again and again. Any time WordPress.org clamped down on search engine optimization tactics, in themes for example, irate community members would bring up Hot Nacho.

Jonas' first few weeks at WordPress Inc. got off to an explosive start, and over the next few months he continued to work unpaid as WordPress Inc.'s only employee. He got in touch with major web hosts and created partnerships so that WordPress.org could make money by recommending hosting companies. He met with venture capitalists to talk about where WordPress was going.

At an IRC Meetup in August 2005, Matt discussed some of the ways he wanted to see the project supported. Instead of fundraising, he wanted to see a company that could generate revenue. He said that "the goal, eventually, is for it to be the biggest contributor someday, supporting community members to work on WP full-time." To protect the project from company liabilities, donations would be kept separate. This would ensure that if the company was sold, the project would be safe. In this chat, the "inc." that Matt refers to isn't WordPress Inc., but the as-yet-unannounced Automattic. When asked about employees, he said that the only one was Donncha, with Ryan Boren planned for the future. WordPress Inc. itself petered out, disappearing with much less fanfare than when it arrived. There wasn't money available in WordPress Inc. to pay Jonas a salary, especially when Matt was using his own salary from his job at CNET to pay Donncha to work on WordPress.com.

The wider community was confused about what had happened with WordPress Inc., especially those who had watched Matt announce the company's launch on stage. In response, Matt posted a page on the WordPress Codex, explaining what had happened:

At the WordPress 100k party in March 2005, I talked about the formation of a "WordPress Inc." with Jonas Luster as the first employee. That never really got off the ground, I continued my job at CNET and Jonas (who I couldn't afford to pay a salary) ended up going to work for Technorati. It wasn't even planned to be announced at the party (since it wasn't clear logistically how it would happen) but everyone was really excited about it and I had an extra G&T (or two), we all got carried away.

The first movement toward making money to support WordPress was more of a stumble than a step. It did produce some important lessons, however, about how to run a business alongside a free software project. In any attempt to run a business based on a free software project, the company is beholden to two players: the company itself and the community. In terms of the company, investors have to be kept happy and employees have to be looked after. The company needs to make money. On the other hand, it is the community that is invested in growing the free software project, and assuring its integrity and independence. Walking the line between the two can be difficult for any community member, but particularly for a project founder or lead who has multiple reasons for securing the future of both.

16. WordPress.com

As WordPress Incorporated fizzled, Matt pitched a WordPress-based blogging network to his employers at CNET. Many major internet companies had blogging networks including Google, Blogger, Yahoo 360, and Microsoft Spaces. CNET also owned several domains, like online.com, that seemed perfect for a blogging network.

CNET decided against it, but the idea didn’t disappear. Matt decided to build a blogging network himself. fn-3

First, he needed the WordPress.com domain name. At the time, it was owned by Open Domain, an organization that registered domains and gave projects permission to use them in return for acknowledgement. It was unclear whether Open Domain was squatting on domains, or genuinely trying to help free software communities. (They'd also registered Drupal.com, then donated it to Drupal without incident). The WordPress community was understandably perturbed by the idea of someone squatting on WordPress.com. Owning the domain was key; there was little security in a blogging network without control of its own name.

After months of wrangling, Matt acquired the WordPress.com domain and work began. Donncha, as the developer of WPMU, was a perfect candidate -- and fortuitously, was looking for new work opportunities. When Matt emailed the WordPress security mailing list to see if anyone was interested, Donncha got in touch.

The new WordPress.com ran WPMU trunk. Development was fast. Donncha worked on two servers and live-edited code. Without users to worry about, he moved quickly. He improved user-focused functionality and built network administration tools. The WPMU community helped, submitting patches to clean up admin screens. Features like domain mapping and tags, which didn’t sit well in WPMU, went into plugins.

Andy Skelton (skeltoac) was WordPress.com's second employee -- and first acquisition. Andy had developed Blogs of the Day, a self-hosted stats plugin that produced a list of each day's most popular blogs. After meeting him in Seattle, Matt brought Andy on board to create a stats plugin for WordPress.com based on Blogs of the Day which, for a number of years, was featured on WordPress.com's home page.

WordPress.com opened to signups in August 2005, by invitation only, to control user growth on untested servers. Many who were involved with the WordPress project got WordPress.com blogs, including Lorelle VanFossen and Mark Riley. Every new WordPress.com member also got one invite to share.

People could also join by downloading the Flock browser, a browser with built-in social networking tools. “I thought Flock was the future,” says Matt. “First we did invites, and then we thought well, we’ll allow you to bypass an invite if you’re using Flock because then we’ll know that you’re kind of a social, in-the-know person.” Flock integrated with WordPress.com, and users could use it to post straight to their blogs.

Both of these measures -- invites and Flock -- allowed WordPress.com to grow in a steady and sustainable way. Putting in sign-up barriers controlled the flow of people and helped ensure scalability. Nevertheless, demand quickly outstripped supply; one invite even landed on eBay. The influx of new bloggers also brought demands for support. Without a clear distinction between WordPress.com and WordPress.org, many bloggers made their way to the WordPress.org forums looking for help. This caused some discontent among WordPress.org forum volunteers, who felt that they were doing free work for a service that would eventually become commercial.

The first attempt at WordPress.com-specific support was an email address. Developers responded to the messages, diverting their attention from writing code. “I found that I would spend half my day replying to users,” recalls Donncha “and then being completely wrecked in that your mind is completely taken off programming new features, or improving things, fixing bugs, just because this whole thing is so tiring.” Plan B was a mailing list, followed by WordPress.com-specific community support forums.

Eventually, support moved to a ticketing system led by Mark Riley, a veteran of the WordPress.org support forums who became WordPress.com's sixth full-time employee. For a long time, he was solely responsible for support, closing nearly 50,000 requests on his own. The next support person joined in 2008; today, WordPress.com users have a robust community on their own forums and a huge team of "Happiness Engineers" supporting them. (Although it's still not unusual for WordPress.com users to land on the WordPress.org forums.)

Creating a user-focused blogging platform like WordPress.com made sense in the context of the WordPress project: WordPress has always been focused on its users, on people who might not understand the mechanics of a server, but still want a website. WordPress.com took this accessibility to the next level, letting people fill out a form to get a blog with the power of WordPress. Still, WordPress.com is a balancing act, trying to satisfy those who want a simple website builder, with those who want the flexibility and power of the core WordPress software, and providing a middle ground for people who want a website without building one from scratch.

However, a hosted service like WordPress.com needs a revenue stream to pay for server costs, run the software, provide support, and pay staff. The free software project, with its haphazard donations and income from hosting companies, couldn't maintain such a network on a wide scale. WordPress.com needed a supporting business focused on WordPress’ main audience: software users.

While the business end was coming together around the developers who had built WordPress.com, Matt was working on another product that would influence the WordPress community, an anti-spam plugin called Akismet.

17. Akismet

Online spam is the old annoyance of unsolicited mail, writ large and filling digital inboxes worldwide. Initially limited to email, it quickly became a blog issue: blog comment forms allow anyone to enter data, and any opportunity for data entry is a doorway for spam. WordPress, like every other blogging platform, is susceptible. Developers were working on anti-spam solutions as early as 2005, with plugins like Spam Karma and Bad Behavior.

Matt was also working on an anti-spam solution. His first attempt was a JavaScript-based plugin that modified the comment form to hide fields. Spammers downloaded it, picked it apart, and learned to bypass it within hours of launch. This is a common pitfall for anti-spam plugins; any widely-adopted plugin quickly attracts spammer attention, and a work-around soon follows. Regrouping, he tried a new tactic: crowd-sourced spam reporting. In late 2005 Matt launched the Akismet plugin for WordPress. Akismet -- short for "Automattic kismet" -- used the power of the community to create a plugin that evolved alongside spammer tactics.

Each time someone comments on a website running Akismet, Akismet checks the comment against all the spam in its database. If the comment is identified as spam, it's deleted. When spam comments inevitably get through, a site owner can mark them as spam to remove them and add them to the database. This means that as all the site owners using Akismet report spam, the pool of spam comments in the database grows, making Akismet more and more effective over time. “It’s like all the kids on the playground ganging up against a bully.” says Matt, “Collectively we all have the data and the information to stop spammers, certainly before they’re able to have a big impact.”

In November 2005, the wp-hackers mailing list discussed plugins to bundle with WordPress core, and an anti-spam solution topped the wish list. Akismet came up, though not everyone was comfortable using a plugin with a commercial element; Akismet is only free for non-commercial use. (Payment is based on an honor system that asks commercial users to self-report.) Some questioned Akismet's data collection and storage methods. Akismet had one other significant shortcoming: it required a WordPress.com account, and WordPress.com hadn’t officially launched. Using Akismet meant using WordPress.com, which meant finagling an invitation or downloading the Flock browser.

Despite the pushback, there was an equal amount of support. Some didn't find the pay-what-you-want system jarring, arguing that Akismet has server costs to cover. When WordPress 2.0 beta came out that month, it was bundled with Akismet. WordPress.com opened to the public two days later, making both services available to anyone.

Concerns that a money-making plugin ships with WordPress continue. Discussions about Akismet surface perennially in the community, including among core developers and at core team meetups. "It seems an unfair advantage (for Automattic) and it cuts against WordPress' goal of openness," says Mark Jaquith (MarkJaquith). "That being said, spam is still a huge problem and Akismet is still the leading product, even though there are now alternatives."

The public nature of WordPress development makes it difficult to develop a widely-adopted anti-spam tool. Dealing with spam via a service means that the plugin code itself can be open source, while the algorithms for identifying spam remain private. While there are often discussions about recommending a selection of anti-spam options rather than bundling Akismet with WordPress core, this isn't yet viable. "The moment we recommend five plugins," says Andrew Nacin (nacin), "the spammers will all target the other four that don’t have the ability to evolve and learn like Akismet does."

The problem of spam highlights the challenging intersection between business and free software: including a freemium plugin with WordPress doesn't gel with the software's openness goals, but removing it would have a detrimental effect on users, contravening the project's user-first principles. Akismet is still bundled with core, and the debates continue.

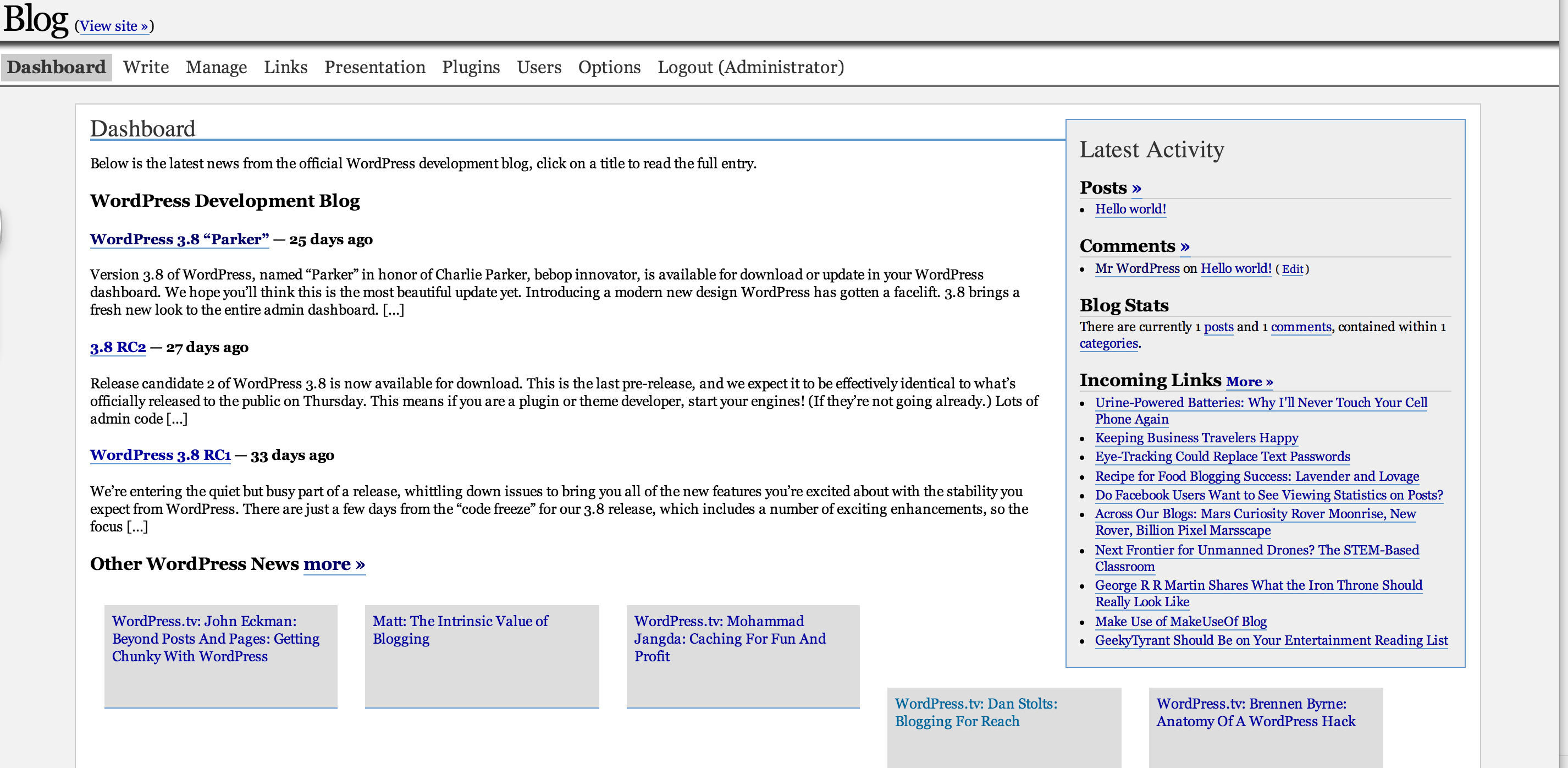

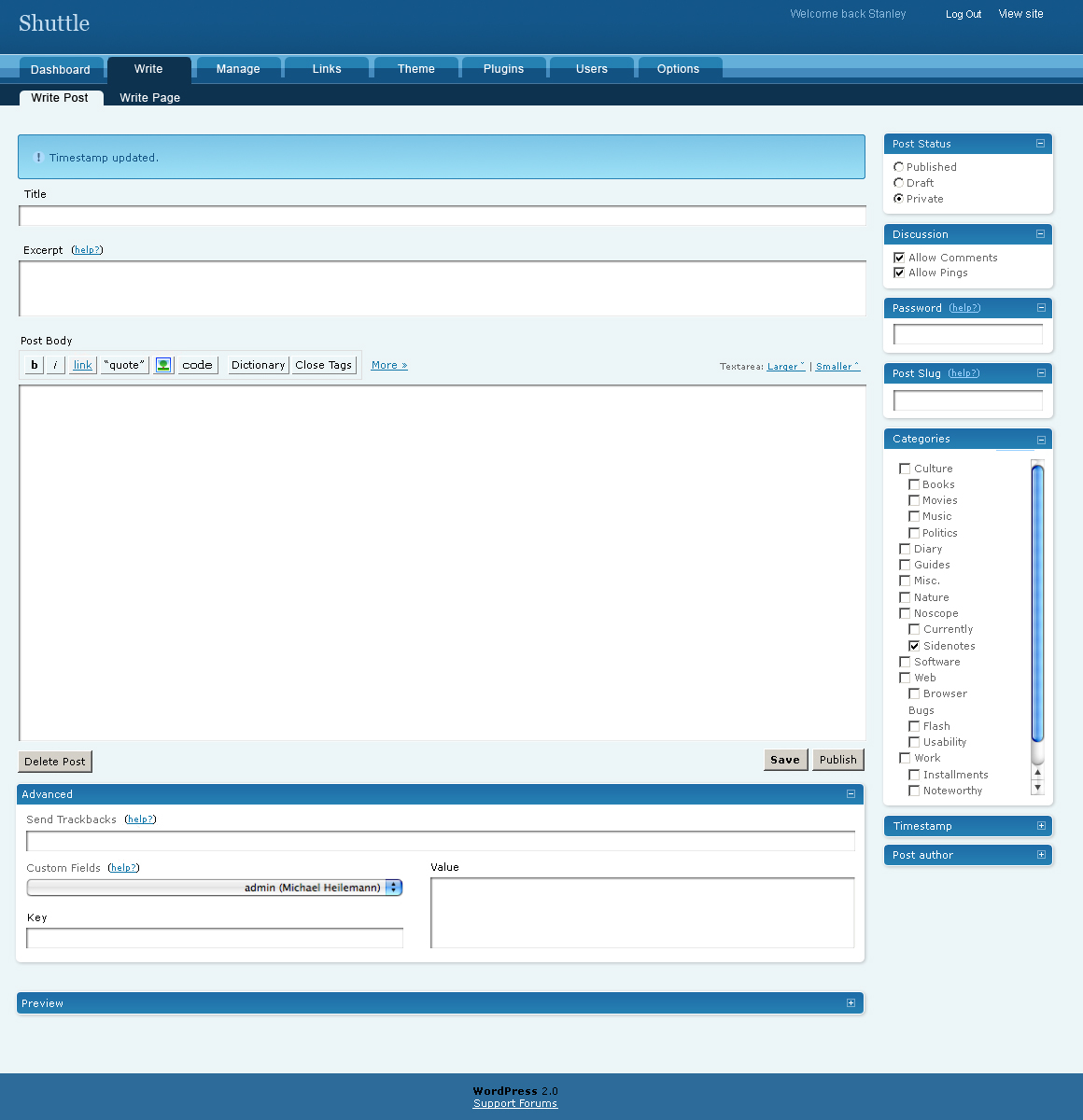

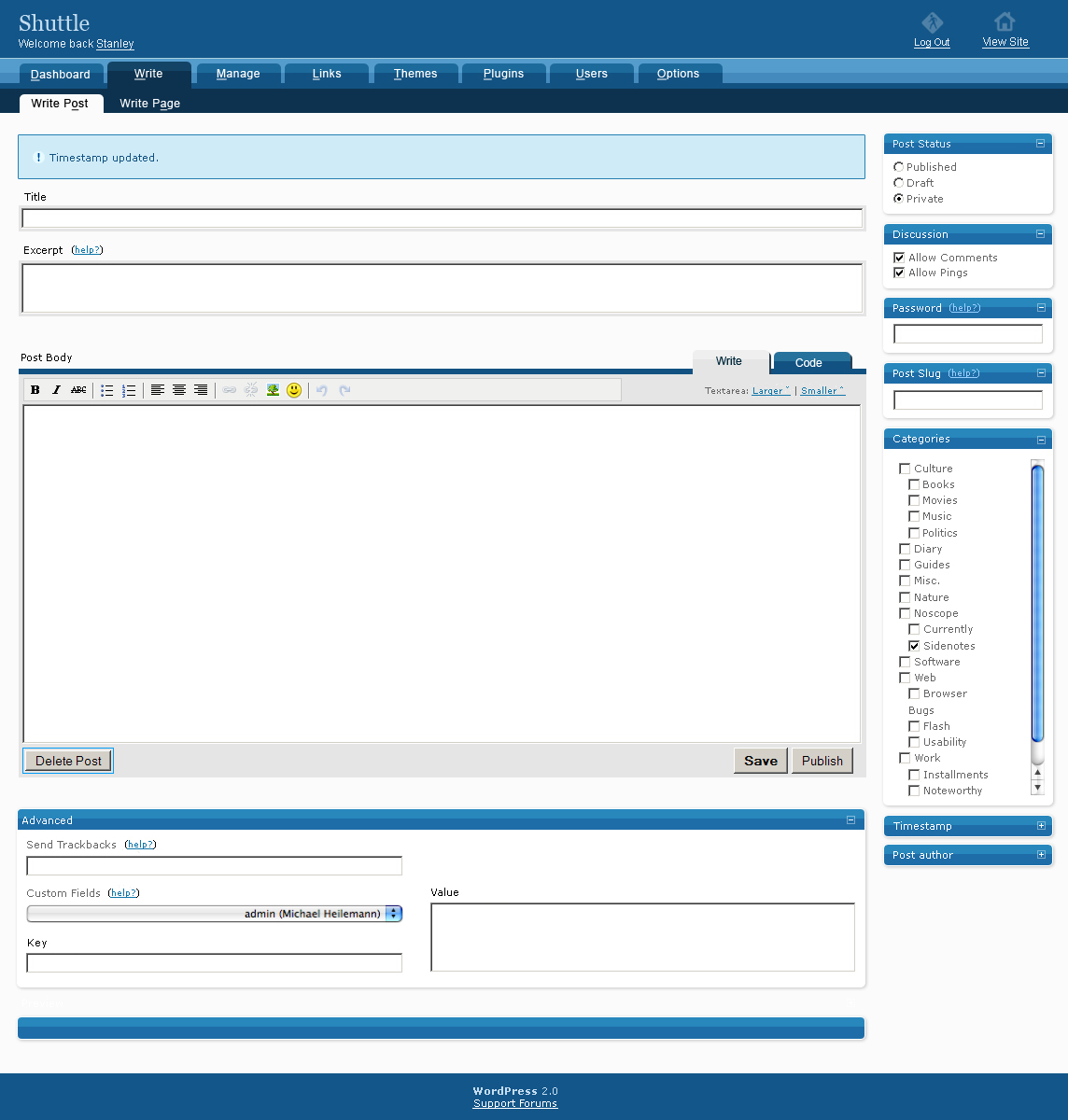

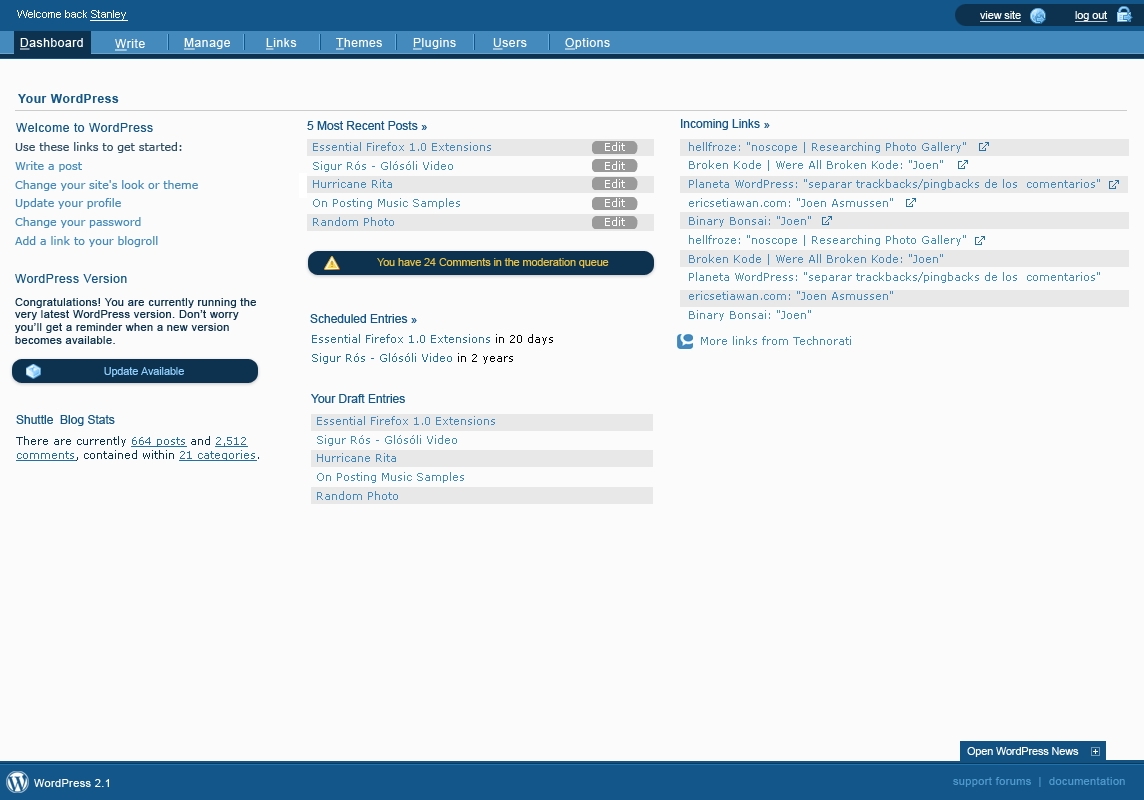

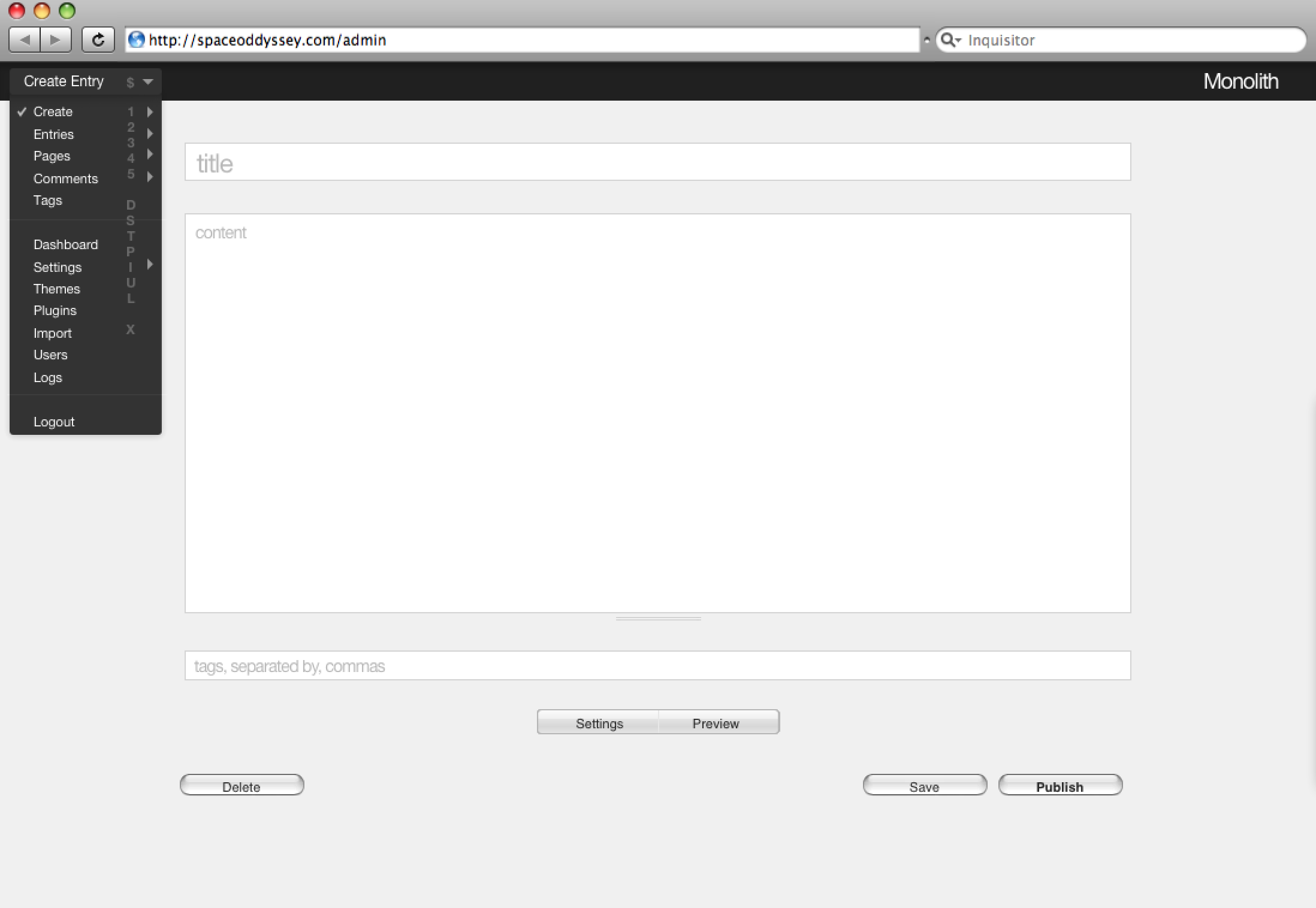

18. Shuttle

As people experimented with ways to make money with WordPress, design changes were underway in the interface. Between 2005 and 2006, the WordPress community organized the "Shuttle" project to overhaul WordPress' admin screens. Their aim: to create a coherent, distinct look for WordPress by redesigning wp-admin, which had inherited its design from b2.

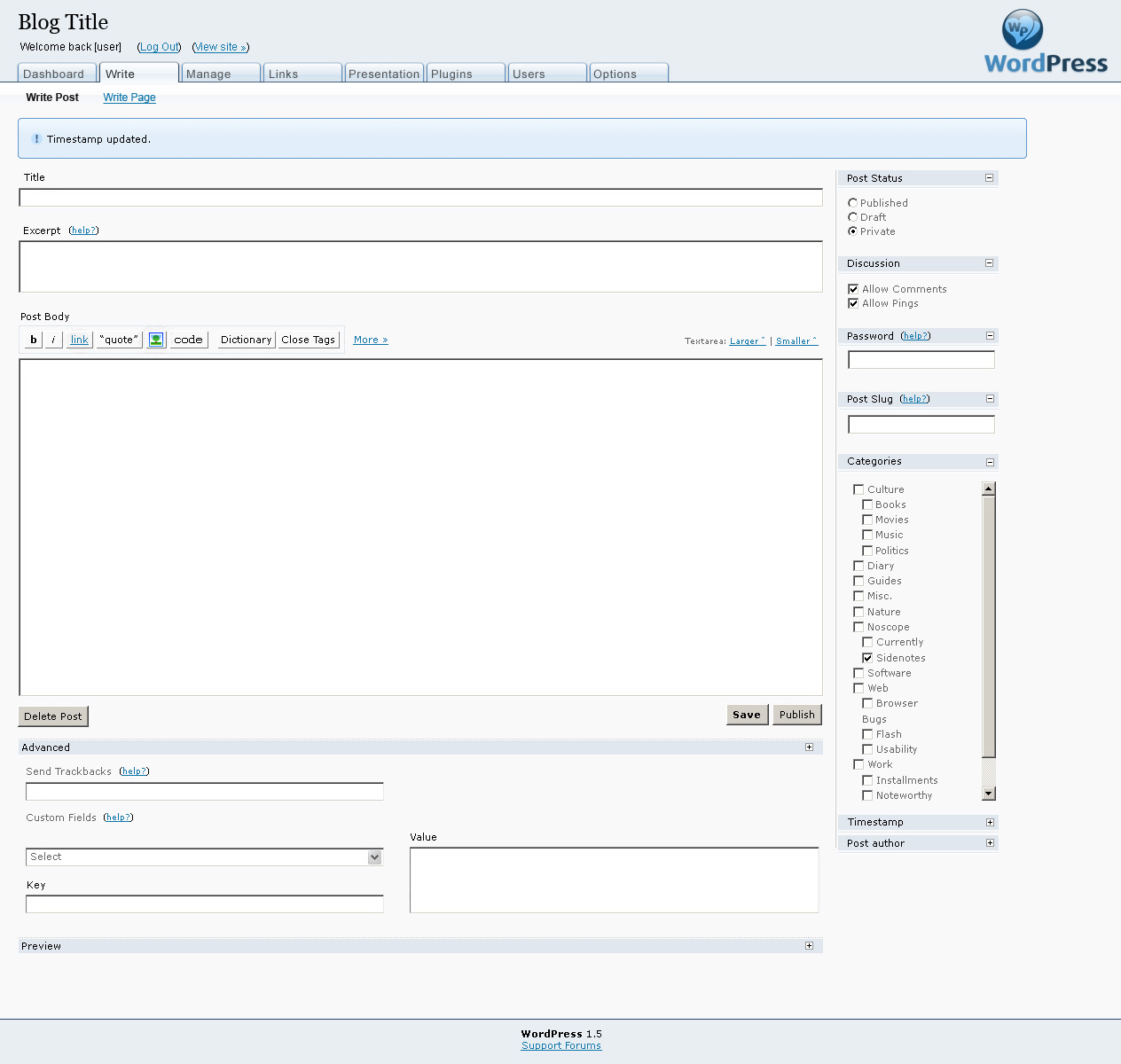

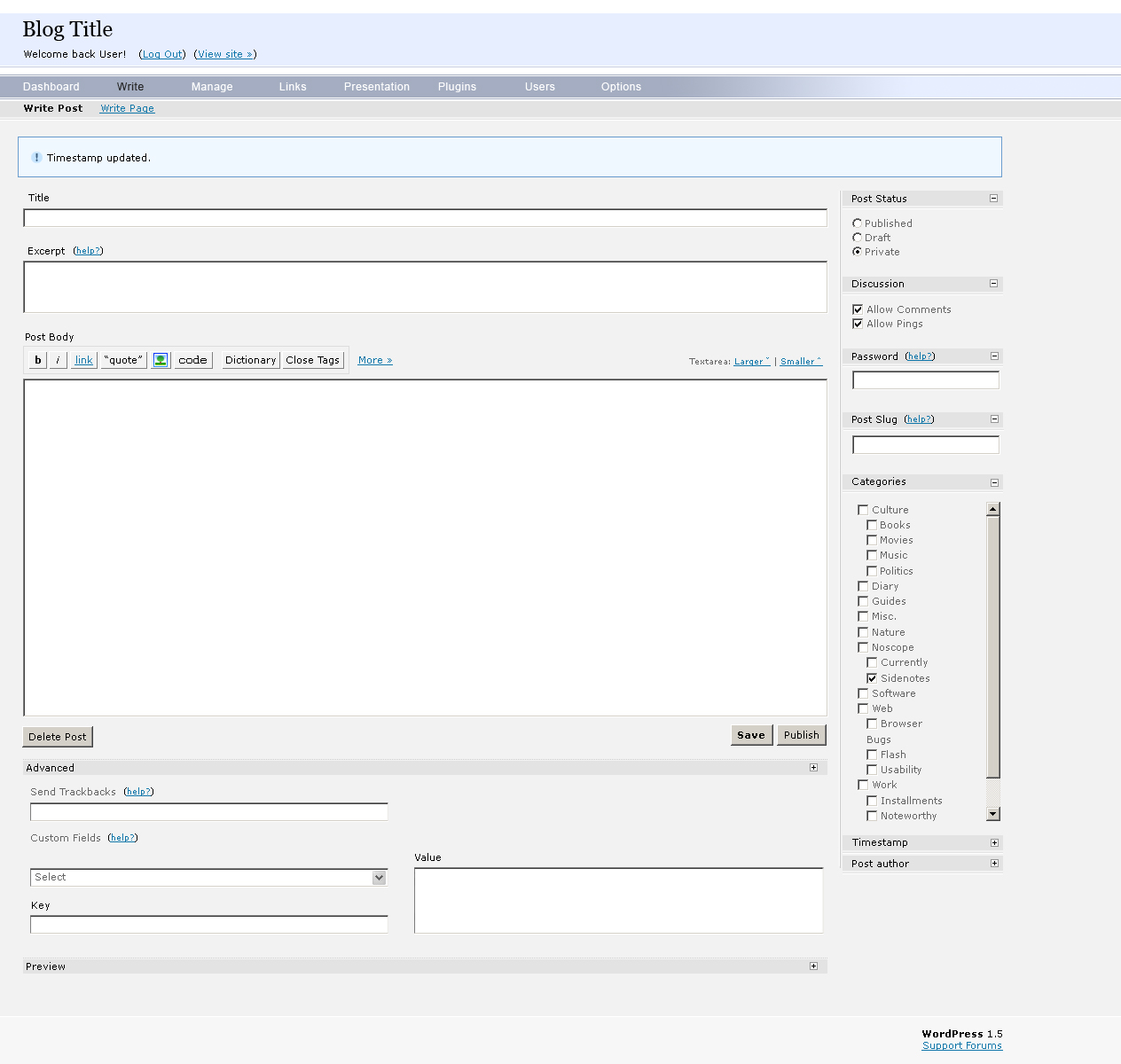

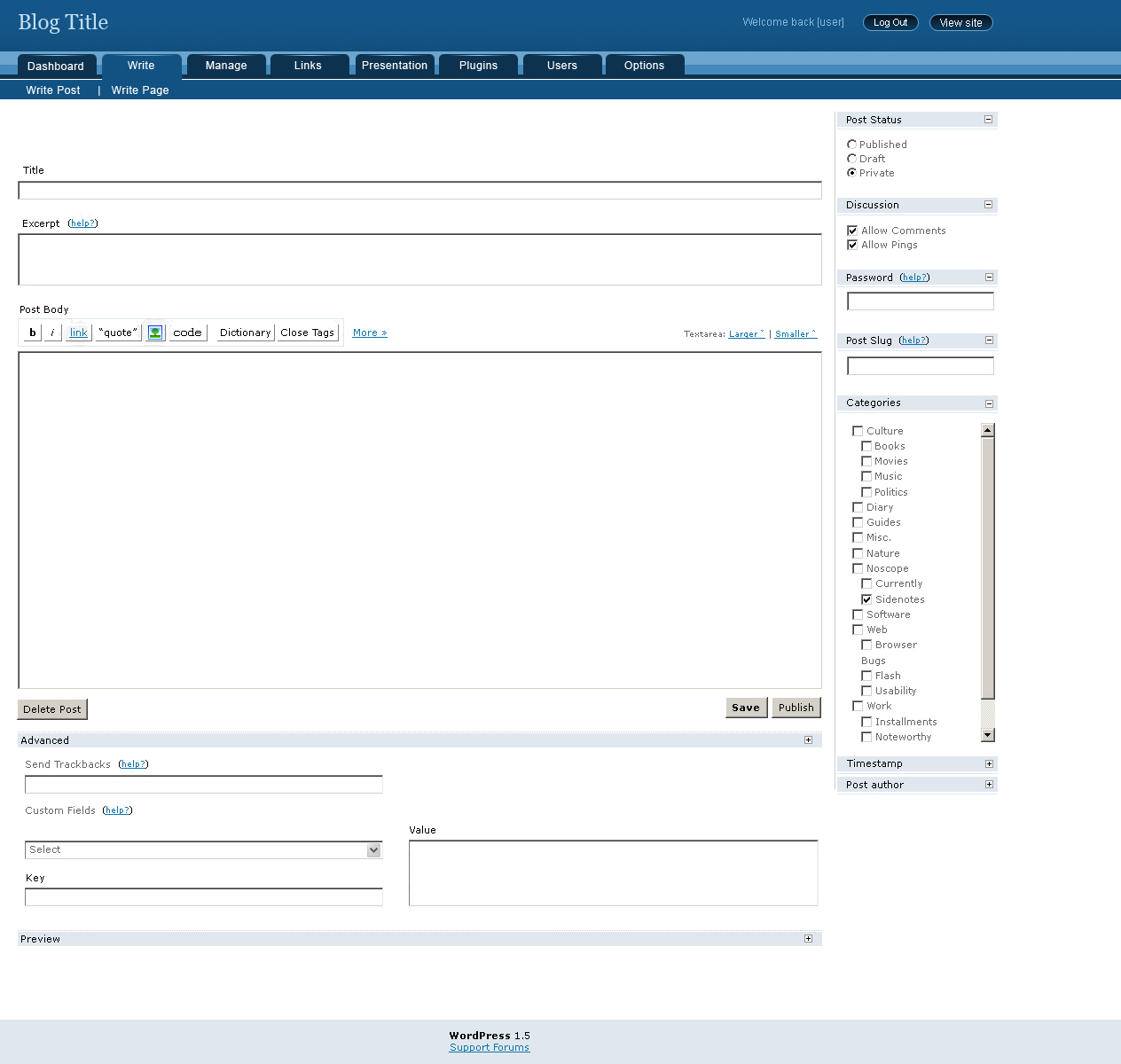

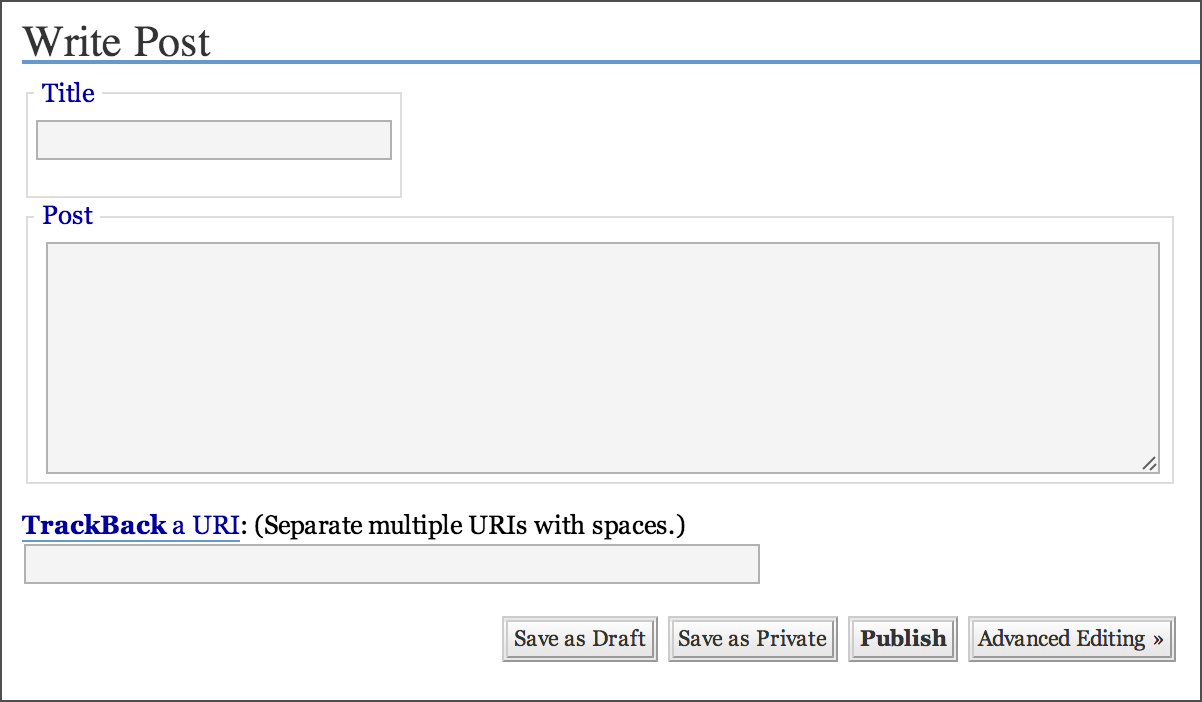

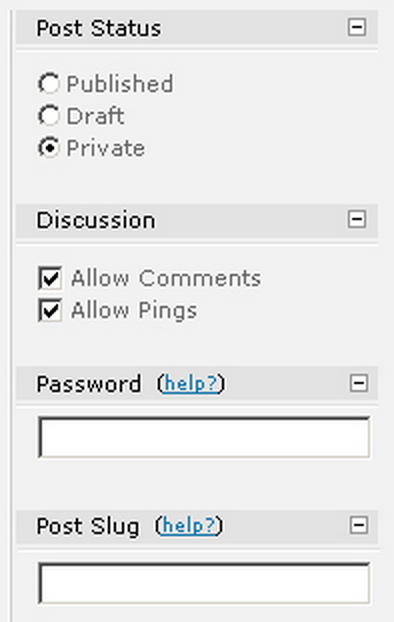

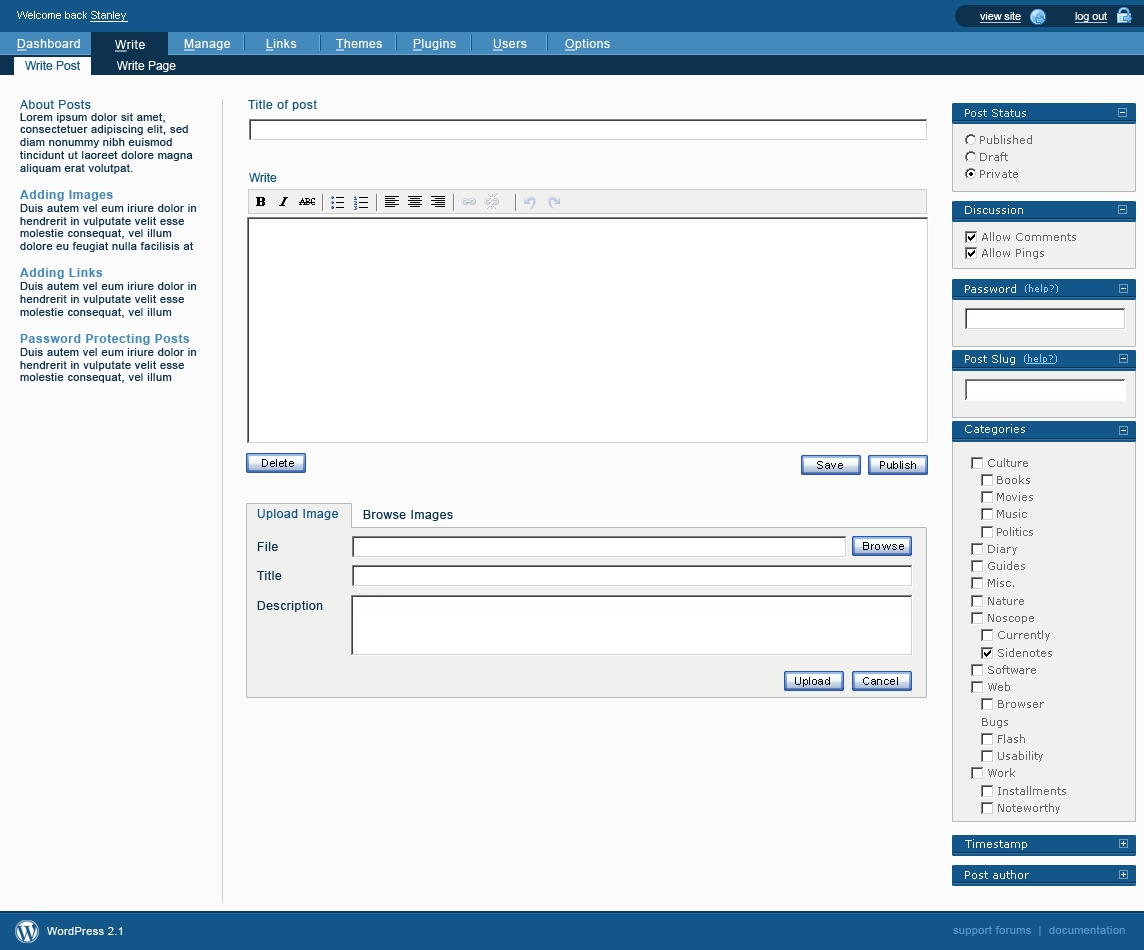

The group's aesthetic refresh reimagined and modernized wp-admin, iterating on the design without re-architecting the interface or adding new features. They started work in the wake of WordPress 1.5, which came out with a set of admin screens ripe for improvement:

Just as dealing with spam revealed tensions in the development process, Shuttle's work highlighted a pressure point: squaring coherent design and free software development. Design decisions, which are usually highly subjective, seem not to lend themselves to a public process. To work effectively, Shuttle felt they needed to tweak their methods.

Linus's Law, outlined by Eric Raymond, says that "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow." If there's a bug in the software, make the code available to many people; someone will see the solution. For an issue with a defined answer, this can speed progress considerably. With design so subjective in nature, however, Shuttle designers worried that an open process would lead to too many cooks in the kitchen, and that competing opinions would lead to stalemates.

Unlike WordPress' core developers, the Shuttle group communicated via private mailing list, wp-design. This list was open, but list archives weren't public. To be involved, a contributor had to be added to the group, and the group had to agree to add the new member. Discussions among members indicate that they deliberately tried to keep the group limited. "An open mailing list would become so much noise and so little signal so quickly that there would be no way we could move forward," recalls Chris Davis.

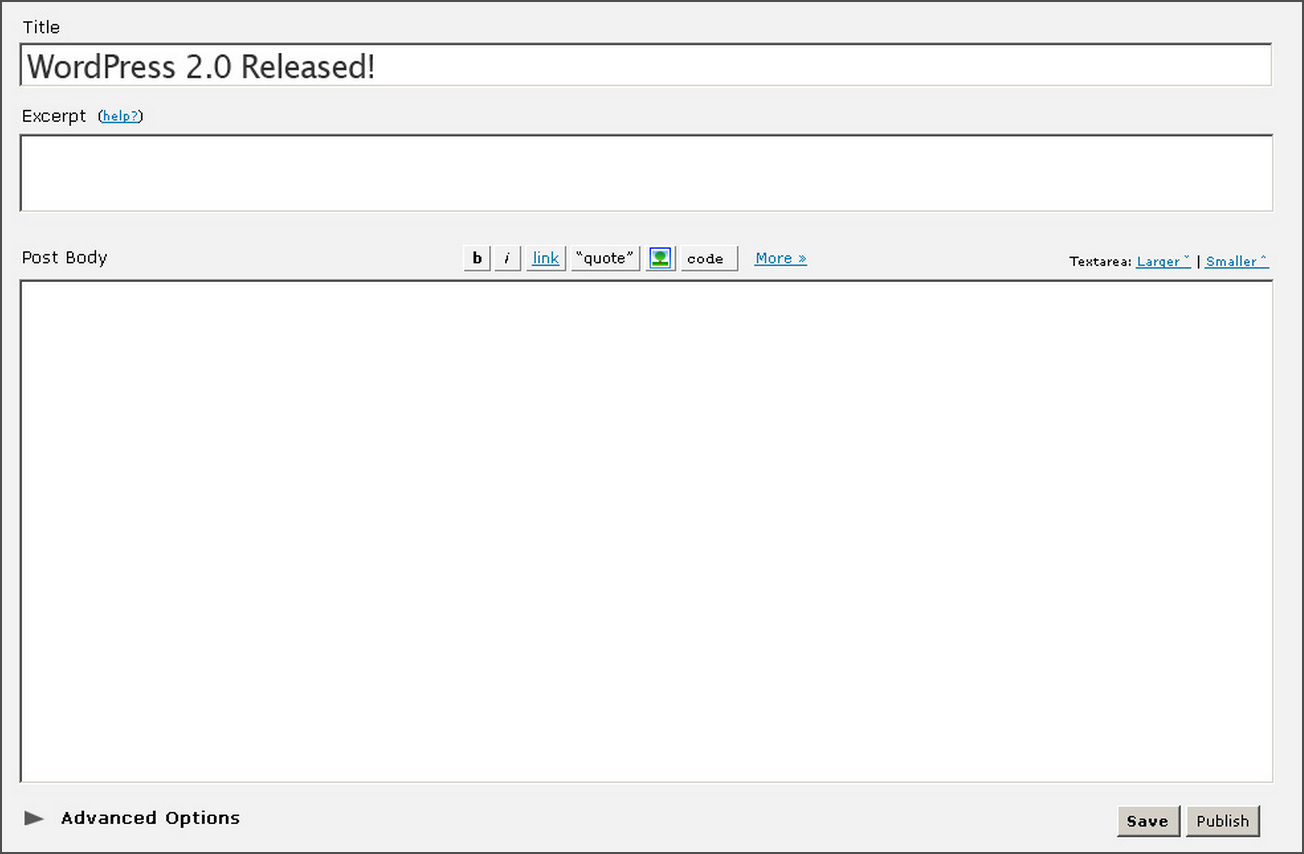

The group remained small, with three main designers -- Michael, Joen, and Khaled -- supported by coders responsible for realizing the design vision. The group sent designs around among themselves, offered feedback on one another's work, and iterated on the design. They focused on specific elements, mainly the Post screen (post.php). Over the course of the project, twenty-eight versions circulated among this group.

Version 8

Version 14

Version 21

Version 26

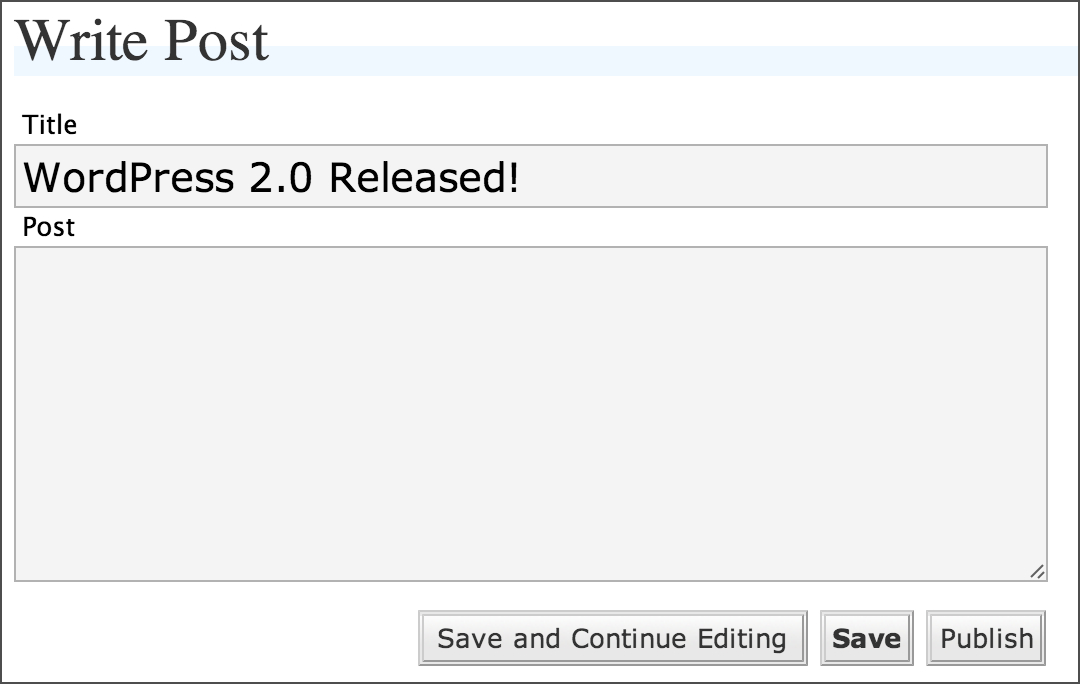

As the design process continued, elements of Shuttle were implemented in WordPress. One of the earliest Shuttle designs increased the size of the title field in the post.php edit screen.

In WordPress 1.5:

In Shuttle:

WordPress 2.0:

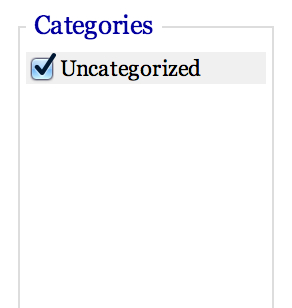

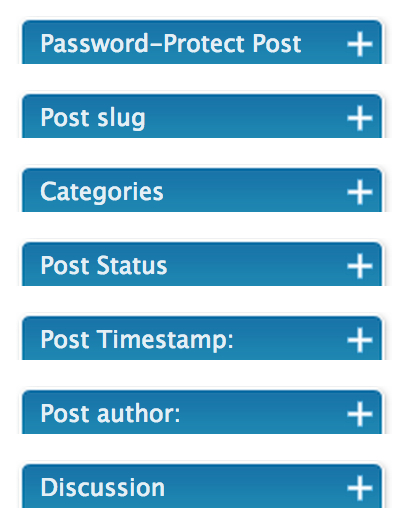

Another iteration of the post.php screen collapsed elements like post status, categories, and author.

In WordPress 1.5:

In version 8 of Shuttle:

In WordPress 2.0:

When WordPress 2.0 shipped with Shuttle-inspired changes, the feedback wasn’t entirely positive. Molly Holzschlag wrote that "what WP2.0 has gained in interface appeal it's lost in some practicality too." Piecemeal implementation of their vision kept the Shuttle group from creating a single, cohesive redesign.

The project was beset by other problems. Despite the closed mailing list, progress stalled without a clear leader charged with the project's overall vision. When one skims the mailing list's archives today, it reads like a design-focused discussion forum rather than the communications of a focused team with a clear task. As the Shuttle team discovered, a group of independent designers, each with their own ideas, can trip up design work as surely as a mailing list full of hackers.

It took the group a long time to complete work. They discussed minor design elements like rounded corners and gradients for lengthy periods, rather than examining the fundamental needs and wants of WordPress users. "I don’t know if we were cooperating enough on getting a unified feel and a unified understanding of everything before we tried to actually apply our ideas to the problem," says Michael. Besides that, the contributors had jobs that absorbed their time, so work happened in fits and starts. While the original plan was to complete the admin redesign within three months, by mid-April 2005, this slid to September. The team eventually missed the deadline for WordPress 2.0 in late 2005. The next deadline (for inclusion in WordPress 2.1, which itself never materialized) was the end of January, though it was March 2006 before a complete set of mockups arrived.

It was then that Khaled sent out a comprehensive set of screenshots with his vision for the new WordPress admin:

The rest of the group loved the designs, and the developers began coding. Still, development dragged on. In mid-April, Michael Heilemann withdrew from the project, saying that he had to prioritize other commitments. The same month, Khaled asked whether Matt or Ryan would ever get around to implementing the design. The response placed the redesign as a medium priority. Changes would be iterative.

On May 14 2006, Khaled posted a complete set of designs to his blog, bringing the Shuttle project to a close. He was still under the impression that the mockups would be implemented in due course. They never were. Khaled and other members of the group felt disenfranchised, and drifted away from the community. Chris Davis and Michael Heilemann made the switch from WordPress to the Habari project.

The biggest failure of the Shuttle project wasn't the designs or implementation, but the process itself. To avoid getting bogged down with too many opinions, the group closed itself off from the community -- which created a new set of problems. Isolated from the larger community, they lost touch with the development process. The project's closed nature limited opportunities for other enthusiastic designers to step in and move the work forward. For each person excited to see a spectacular WordPress redesign, there was another person resentful that a blessed group of designers was working privately on something the whole community had a stake in.

In one of the final emails on the wp-design mailing list, Matt outlined some of the things that he learned about design-oriented free software projects:

- Work should not be done in private

- Design by committee doesn't work, better to break up tasks and let individual people focus on one section

- Focus on lots of incremental changes, rather than giant redesigns (you end up in the same place, and probably sooner)

- Document the process and decisions along the way

- Code concurrently with the designs (and iterate)

- Don't hype it, expectations get out of control

- Avoid scope creep of features into designs

- Set a deadline and stick to it

These tenets influenced the relationship between WordPress design and development, helping future design projects avoid the difficulties faced by the Shuttle group.

19. Automattic

It was time to give WordPress.com and Akismet a parent. WordPress, like many free software projects, started as a script built in a hacker's spare time. As the community grew and more people adopted the software, the hacker realized it could be a business -- a for-profit venture, with dedicated employees and a company to cover costs.

In 2005, there weren't yet many businesses run alongside free software projects. Creating a company to house WordPress.com and Akismet would be a delicate balancing act to satisfy very different constituencies. The business is responsible to investors and employees, while the community of contributors has no stake in the business, but a huge stake in the project. Decisions come under scrutiny from both sides. As founder of the project and the company, Matt would be pulled in both directions.

What companies based on free software and their foundational projects share is belief in the power of free, open source software. A WordPress.com company would offer a service and generate income while keeping the core software free and accessible. Making money would be but one aim, alongside popularizing free software for the benefit of society. It seemed to make sense for a business to spring up alongside WordPress, one that shared its commitment to the open web and to democratizing publishing, and that would help sustain the WordPress project.

In December 2005, as the memory of WordPress Inc. faded, Automattic launched as a new home for WordPress.com and Akismet.

Automattic marked a new, but challenging, beginning for its employees, who had to balance the free project's aims with the company's commercial goals. It's a balance that has affected both WordPress and Automattic throughout their close histories. The business generates income and provides contributors and support to the project, while the project creates the software that is the foundation of the business. The business needs to grow in a non-destructive, sustainable way, allowing the project to grow, mature, and attract a diverse group of contributors.

The company launched with four employees: Donncha Ó Caiomh, the original developer of WordPress MU, worked on WordPress.com's infrastructure with Ryan Boren, Matt, and Andy Skelton. They left their jobs and put their faith in WordPress -- that it could grow beyond its roots as a small project into a platform that could sustain a blogging business.

In January 2006, Toni Schneider joined as CEO (or "adult supervision" for the still only 19-year-old Matt). Toni was a developer and later CEO of OddPost, a startup that was acquired by Yahoo! and became the basis of Yahoo! mail. After setting up the Yahoo! Developer Network, Toni joined Automattic for a new challenge. Toni had his first encounter with the power of open source while working on OddPost. OddPost didn't have a spam filter and needed one, and an open source project provided the solution. Paul Graham had introduced his idea of Bayesian spam filtering; he open-sourced the idea, and Toni's team implemented it at OddPost. "It just showed me that this is a really powerful model," he says.

He was attracted to Automattic by the challenges of building a product around free software. WordPress already had brand recognition, but no one was yet making money from it. In a 2006 interview he said:

WordPress is an interesting new challenge because it's not like most startups, where the world still hasn't heard of you. WordPress is way past that stage. On the other hand, there is no business yet. Until Automattic came along, there was nobody working for it. It was all volunteers. So taking that product momentum and somehow turning that into a business will be really interesting.

Other aspects of the project attracted Toni: the product wasn't a central, proprietary service, it wasn't owned solely by anyone, but by all of the people involved, and it gave users a say and a stake in a way other hosted services didn't -- anyone can set up a WordPress blog. Unlike a service like Gmail or Facebook, WordPress is something you make your own. The idea of a new kind of company with a new kind of influence was too much to ignore.

Automattic brought together free software development experience with Toni's business experience to build a company organized around three key principles: a distributed workforce, a rapid-release development model, and a user-centric focus. All ultimately trace their roots to principles of open source development that still underpin Automattic today.

A distributed workforce seemed like the natural model. Contributors to a free software project come from all over the world, and collaborate online to build tools that suit their needs. Automattic's first four employees came from four different locations, and the company remains distributed, enabling it to hire people from all over the world based on their skills, not their location -- a global talent pool.

Toni recalls how, in Automattic's early days, people expected its commitment to a fully remote workforce to break down. It goes against traditional business wisdom, which keeps employees supervised, in one place, and focused on hours worked instead of output. The first few employees were experienced at working in a distributed environment; new employees who found it difficult didn't last. Automattic responded by refining its hiring methods, developing a hiring process in which potential employees do a trial, working on real projects in the distributed environment, to see if the company is the right fit for them.

A rapid release model, in which developers constantly push small releases straight to the user, lets Automattic iterate quickly and improve constantly. The company eschews the traditional "waterfall model," in which development follows a strict sequence involving specifications, design, construction, integration, testing, debugging, installation, and maintenance. At Automattic, developers break down features into small components, create patches for each component, and launch code incrementally -- and directly to bloggers. There are few roadblocks, and developers and designers push enhancements and new products to millions of users within a few seconds. Continuous deployment means that by May 2010, Automattic had over 25,000 releases, an average of 16 a day. Rather than optimizing for perfection, the process optimizes for speed.

A distributed workforce and rapid releases work for Automattic because the people who build its products have a direct connection to their customers, doing away with as many levels of mediation as possible. Every person in the company starts their Automattic career with three weeks of direct customer support, with one more week every year, giving each employee the opportunity to see how users interact with the products -- and where the weak spots are. Developers stay happy because they can constantly push new ideas right to customers. Customers stay happy because they're constantly getting new toys to play with, and the chance to share feedback that refines the product.

Following Automattic's launch, the bulk of new hires came from the free software project. Seven of the first ten employees were from the WordPress community, all with an intimate knowledge of developing and using the software. Automattic had a wealth of developers who were not just experienced, but passionate and committed, evidenced by the considerable volunteer time they'd put into it.

From the start, Automattic was both exciting and contentious. It wasn’t obvious where Automattic's boundaries ended and the WordPress project's began. Matt and Ryan, the two developers who led WordPress, were both employees of Automattic, which appeared to make it an Automattic project. It was unclear even on the original Automattic "About" page, which lists WordPress as an Automattic project.

The confusion was compounded by the name of Automattic's blog network: WordPress.com. "We gave the company this advantage of being able to call its service WordPress.com," says Toni. "It's been a curse and a blessing." The mainstream tech press frequently describes Automattic as the "maker of WordPress," which does a disservice to the hundreds of contributors who aren't employed by Automattic. The WordPress.org support forums are littered with questions about WordPress.com from bloggers who don't understand the difference.

On the other hand, Automattic puts millions of dollars into growing the WordPress brand, and a 2013 survey by WordPress hosting company WP Engine found that 30% of people had heard of WordPress. The name recognition increases the number of people opting for self-hosted WordPress sites rather than using Blogger, Tumblr, or other CMSs. There are many more people whose first exposure to WordPress is via WordPress.com, and a number of those eventually move to the self-hosted software. It's unlikely that the free software project would have had the money or the drive to do such extensive branding.

As for-profit entity, Automattic experimented with different ways to make money. Creating an enterprise version was considered, then scrapped -- since WordPress itself can run a blogging network like WordPress.com, producing an enterprise version didn’t make sense. Instead, it offered support services to enterprise-level clients. Prominent sites such as CNET, About.com, and the New York Times were using WordPress, and other sites, such as Gigaom and TechCrunch, shifted to WordPress.com. Automattic initially courted these sites as a marketing strategy, thinking that nothing says "WordPress can scale" better than hosting big, high-traffic sites. Toni approached big websites to offer to host them on WordPress.com; early takers included Scobleizer and the Second Life blog.

Automattic tested different subscription levels. In 2006, they launched the Automattic Support Network at 250 per month.

Just because software is free doesn’t mean that services around that software have to be inexpensive. Companies are prepared to pay enterprise prices to ensure that their websites scale and stay online. Automattic, and other companies in the WordPress ecosystem, had to develop confidence, build up their pricing structure, and charge what they were worth.

20. Growing Pains

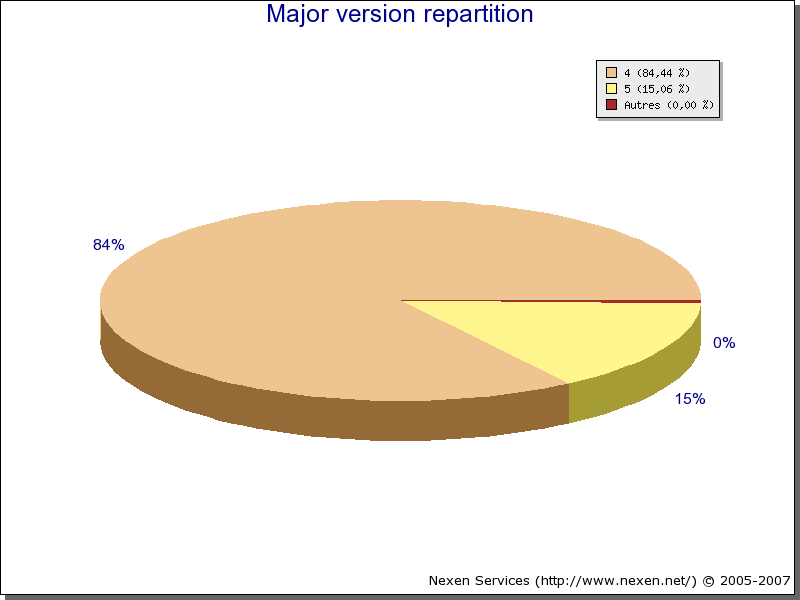

In January 2006, a Google survey found that WordPress powered 0.8% of websites. The project was growing, and with greater adoption came greater tension. Growing pains are common for organizations -- especially in democratic communities where everyone has a voice -- and WordPress was not immune.

WordPress contributors come from a range of backgrounds, and include formally taught developers, self-taught hackers, designers, people doing support and writing documentation, business owners, and bloggers. Contributor diversity is one of WordPress’ strengths, but wrangling so many viewpoints brings its own challenges. Disagreements coalesce around three broad issues: approaches to development and community building, styles of communication, and opinions on who the software is for (users or developers, for example, or users and business owners).

The Shuttle project was but one example. While the participants communicated privately, hoping to streamline and expedite the project, other WordPress contributors were concerned that work was going on behind closed doors and felt cut out of an important part of WordPress' evolution. Co-founder Mike Little was one of those vexed by the process.

In June 2005, the Shuttle project updated the write screen, introducing a new "pods" functionality that let users collapse parts of the screen. The changes were discussed only on the closed wp-design mailing list, precipitating a long discussion on wp-hackers about openness. While Matt saw the commit as a starting point for discussion, others perceived it as a wholesale change made without communication. Many in the community felt that discussion should happen ahead of the commit, and that the community should have been informed about Shuttle's work. That was, after all, how free software projects should function.

IRC discussions focused on Matt and Ryan as bottlenecks; only they had commit access, so all issues had to go through them. After lengthy conversations about how to make the process more open, Mark Jaquith and Sean Evans (morydd) became "bug gardeners," getting maximum trac privileges.

Inline documentation also generated heated debate. Many developers find exploring code a valuable learning tool, and there was strong community support for improving WordPress' inline documentation. However, when Rich Bowen (drbacchus) proposed documenting WordPress' functions, Carthik responded that inline documentation was frowned upon and would lead to bloat. Referring to a thread from May 2005, he offered:

Commenting is tricky. Some "well-commented" code I've seen had a bunch of lines of repetitive filler that "documented" what you could easily see by just looking at the code itself and doubled the size of the program. APIs should be documented religiously, but I think spending a ton of time on redundant comments for code only a few core hackers will ever look at will bloat the codebase and waste everyone's time. I also believe that well-written code usually doesn't need comments unless it's doing some sort of voodoo or workaround.

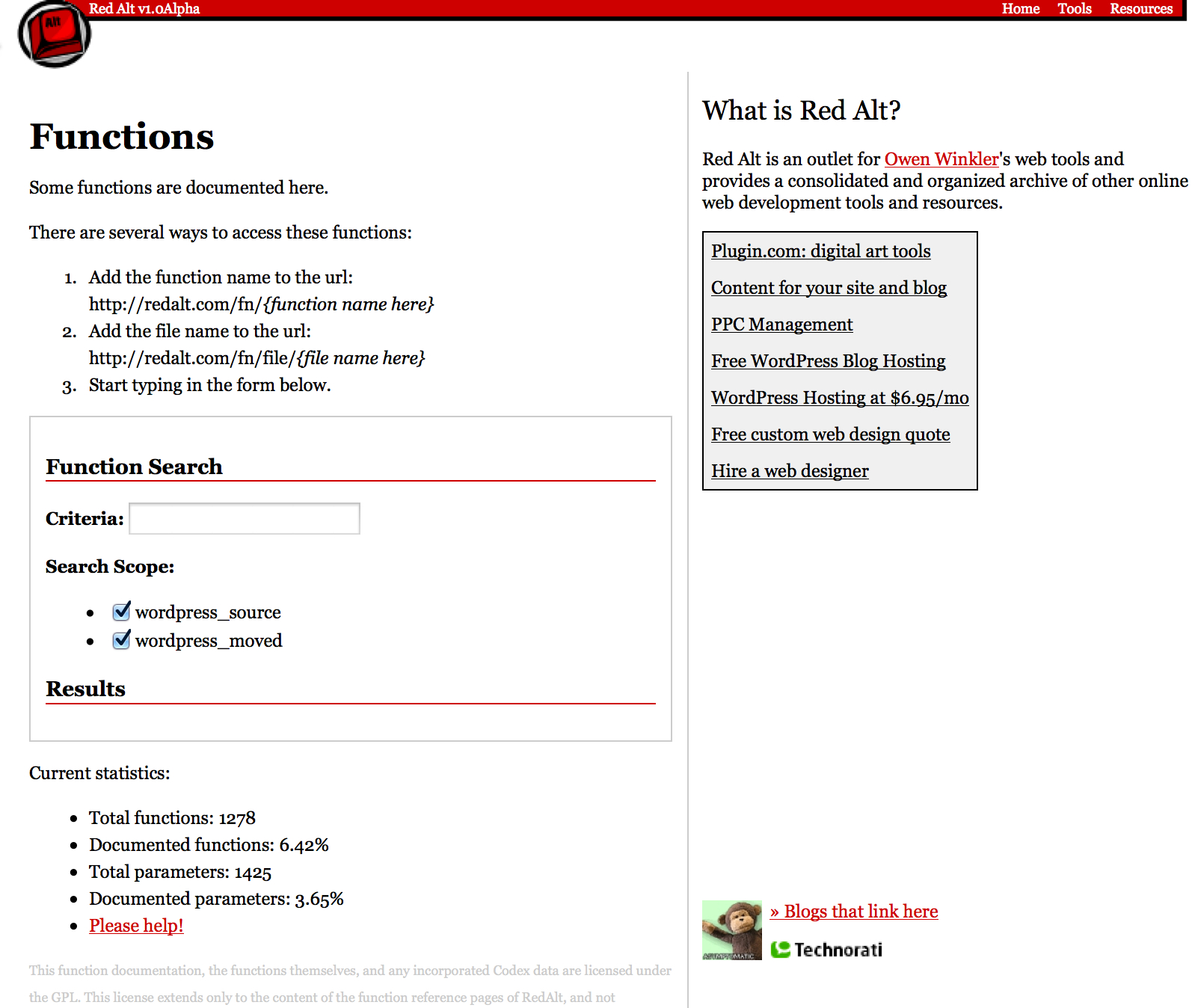

Rich's initial proposal was the first volley in a lengthy back-and-forth about the best way to generate documentation from the code and the best inline documentation format. Matt argued that documentation shouldn't be auto-generated, pointing to the Codex as the best place for documentation, and the conversation ultimately went nowhere despite ongoing community support. Tickets went ignored, and Owen Winkler created his own developer function reference:

Contributors from traditional coding backgrounds also butted heads with the self-taught hackers with whom WordPress is so closely identified, again over documentation. Many original WordPress developers were entirely self-taught. Michel's get-it-on-the-screen approach filtered through the project, sometimes at the expense of coding practices that more experienced developers took for granted -- like inline documentation, which some hackers considered superfluous to writing code, even bloat. It would take some time before it became standard practice in the WordPress community.

Problems weren't limited to inline documentation. Mark Riley, one of WordPress' longstanding forum moderators, pointed out in 2006 the many ways that the WordPress Codex was failing users. The Codex recommended that users hide which version of WordPress they were running -- but the code itself contained a comment asking users to leave the information visible. Instructions were often confusing to less-technical WordPress users; a section on permissions stated that "All files should be owned by your user account, and should be writable by you. Any file that needs write access from WordPress should be group-owned by the user account used by the webserver," assuming that all users would know how to configure this. Because it was so easy for non-technical users to download and install WordPress, Mark argued, documentation should be written in clear, simple language.

Release dates were another fault line. Almost every release cycle, Mark asked for the release date in advance so that he could ensure the support forums were properly staffed to handle the barrage of questions. Again and again, a release would arrive and surprise him. "All I am trying -- and yet again completely failing -- to ask," he pleads "is that IF you want support for the product it would nice to at least let the forums know. You guys just don't see it do you? You really don't have a clue."

Each of these issues highlights the tension between developers and non-developers on the project. WordPress encouraged people from all backgrounds to get involved, but developers weren’t always interested in supporting them. Many developers in the project were self taught, with the free software do-it-yourself attitude -- if they could teach themselves PHP, why couldn’t others? Mark Riley's mounting frustrations are clear on the wp-hackers mailing list, as he repeatedly posts questions from the support forums and requests help from developers.

These challenges are unsurprising. When so many passionate people come together to work on a project, disagreement is inevitable. A free software project is a melting pot of people with different ideas, opinions, and backgrounds.

Conventional wisdom says that this approach to creating software shouldn’t work. But somehow it does. Despite the challenges, contributors stick around, new contributors constantly join, and the project grows. In the end, what matters isn’t the specifics of any one conflict, but how the community resolves them and moves on.

21. WordCamp 2006

The WordPress community has a long tradition of getting together to have fun and work on design and development in person. As early as June 2004, contributors were meeting in San Francisco to socialize and hold "upgrade parties." (Before the days of the one-click upgrade, users had to upgrade their sites individually using FTP; contributors gathered to help people upgrade, or to migrate from other platforms to WordPress.) A dedicated WordPress conference was the next step.

Matt, along with Tantek Çelik, had helped organize an informal technology conference called BarCamp, a series of open, workshop-style events where attendees helped create the schedule. In July 2006, Matt announced that he would host a BarCamp-style event called "WordCamp" later that summer in San Francisco. "BarCamp-style" is a code phrase for 'last minute,'” he joked.

The event -- which he announced without a venue or schedule -- would be on August 5th. More than 500 people from all over the world registered: Donncha flew in from Ireland, and Mark Riley from the UK. When WordCamp did get a venue, it was the Swedish American Hall, a Market Street house that served as headquarters for the Swedish Society of San Francsico.

WordCamp 2006's schedule reflects the project's concerns and its contributors' passions. Mark Riley gave the first-ever workshop on getting involved with the WordPress community, now a staple talk at WordCamps. Andy Skelton presented on the widgets feature that he was working on for WordPress.com. Donncha spoke about WPMU, and Mark Jaquith explored WordPress as a CMS, one of the most-requested sessions. There were presentations about blogging and podcasting, and about journalism and monetizing.

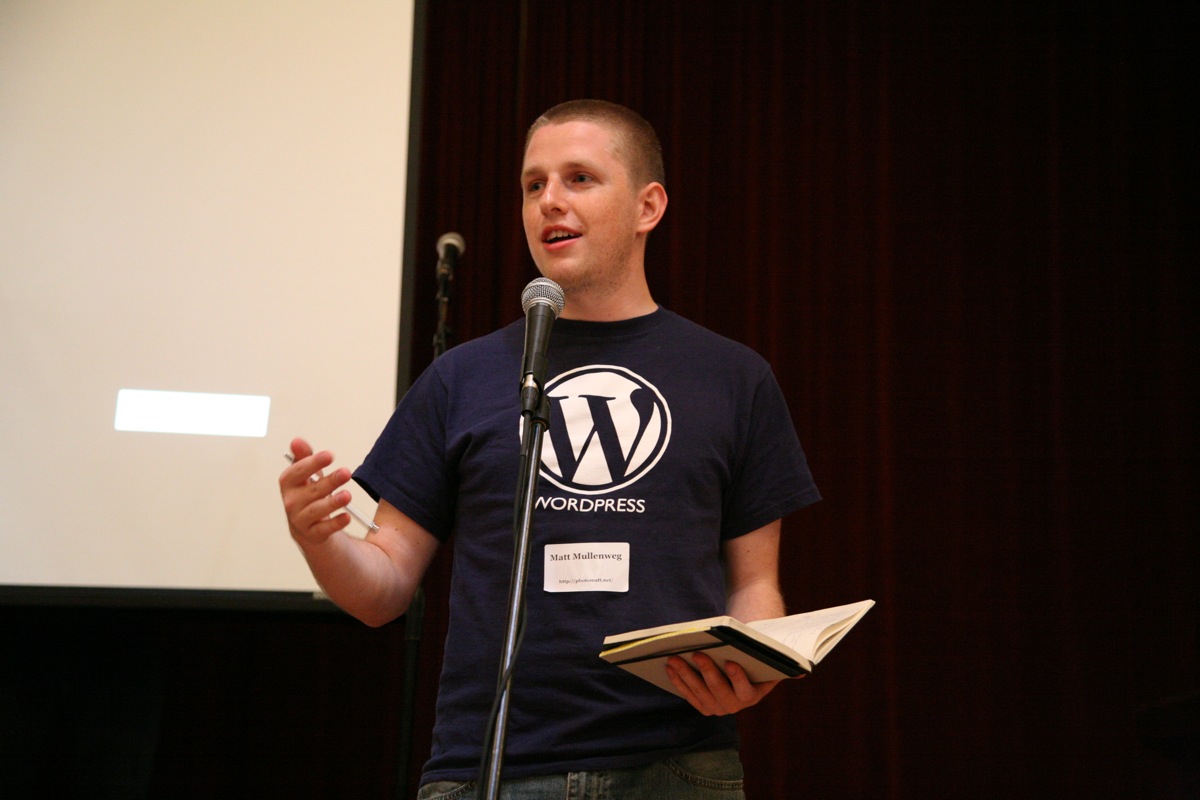

The first WordCamp. (cc license Scott Beale (Laughing Squid))

WordCamp San Francisco 2006 also saw Matt's inaugural "State of the Word" presentation, in which he focused on keeping the software simple, with streamlined installation and user-friendy theme and admin pages. He invited more people to contribute to documentation and support, highlighting Mark Riley's work, and discussed future updates in a Q&A afterwards. This WordPress year-in-review and "coming soon" talk has been a feature of every WordCamp San Francisco since (and in 2015, of the first-ever WordCamp US in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

Matt giving his State of the Word presentation. (cc license Scott Beale (Laughing Squid))

The event, despite the short lead time, was a success and the first of what would be a global conference series. WordCamp returned to the Swedish American Hall in 2007, to be followed by WordCamp Beijing in September 2007 and additional WordCamps in Israel, Argentina, and Melbourne, Australia.

Mirroring WordPress itself, these events are organized and supported by volunteers. There was no formal WordCamp program -- if someone wanted to organize an event, they did it. Like their BarCamp ancestors, they remained informal and user-led. It wasn’t until later, when the project had grown and the number of WordCamps across the world exploded, that WordCamps started to get some structure.

23. Trademarks

In March 2006, Automattic filed to register the WordPress trademark, and the competing interests of WordPress (the open-source project) and WordPress.com (the commercial enterprise) again clashed.

Trademark registrations can be slow processes; a registrant has to demonstrate that they're proactively protecting that trademark. Toni Schneider spent many of his early years at Automattic doing just that. It was a challenge, he says, to figure out “how can we make this a very open brand that lots of people can participate in but it doesn’t just turn into some mess that doesn’t mean anything in the marketplace because everybody just uses it in different ways.” The large ecosystem around WordPress can make it difficult for users to know who they’re dealing with: the official project? Automattic? A third-party developer or consultant? Avoiding trademark dilution was critical to ensure clarity.

Any trademark can, over time, become generic: the meaning of the name morphs from identifying a specific thing to an entire class. The word “aspirin,” which is used as a general term for a class of medications in the United States, is actually a registered trademark of Bayer in 80 other countries. Office machinery company Xerox once ran an advertising campaign to dissuade people from using "xerox" as a verb. The onus is on the trademark owner to prevent their trademark from becoming generic.

The first meaningful attempt to protect the WordPress trademark sought to establish control over the domain. To successfully register a trademark, the owner has to enforce the trademark consistently. For WordPress this meant a domain policy -- a ban on using WordPress in top level domains for any sites other than WordPress.org and WordPress.com. Just before filing, WordPress.org created a domain policy requesting that community members not use "WordPress" in their domains. Once the application was submitted, Automattic began enforcing the domain guideline to protect the WordPress trademark. Many websites used WordPress in their domain names -- community websites, businesses selling WordPress products and services, WordPress fans, and more. There was confusion about what people could and couldn’t do. Could community members use WordPress in the title of their website? Was it okay in subdomains?

In a comment thread on Lorelle VanFossen's popular blog, community members wonder whether they can use the label "on WordPress" (as in "Lorelle on WordPress") on their blogs. After lengthy discussion in the comments, Lorelle updated her post to add:

After many discussions with Matt and the WordPress Community and staff, it is official. It is a violation of trademark to use WordPress in your site’s domain name. You may use it in the title and in blog posts, however, please note that using WP or WordPress in the site title implies the site specializes in WordPress content. Don’t disappoint.

The new policy influenced everything from community sites to businesses. International WordPress groups that had set up their own websites -- wordpress.dk, wordpress.fr, wordpress.pt -- were particularly affected. These community gathering points often had translated documentation, links for localized versions of the software, and support forums to make WordPress fully available to non-English speakers. To these groups, the domain policy felt like a top-down order rather than a community decision. For others who believed that the WordPress name and logo belonged to the project itself, domain restrictions seemed counter to the WordPress ethos.

Also affected was wordpress-arena.com, a site running a WordPress theme contest. After Alex King’s 2005 CSS competition, theme competitions became popular community events. The contests had clear community benefits, increasing the pool of themes, allowing developers to show off their skills, and pushing the boundaries of theme development. Although he enforced the domain guideline, Matt left the site a message of support, also noting that "Unfortunately for every cool usage (like this competition, potentially) there are a dozen scammers and spammers misusing WordPress, selling spamming scripts or copies of WP itself."

Six months later, official cease and desist letters went out to sites still using WordPress in their domains. Attention centered on two commercial websites, wordpressvideos.com, run by Brandon Hong, and Sherman Hu's wordpresstutorials.com. Both were registered prior to WordPress’ trademark policy, and presented a unique trademarking challenge. The main test of trademark violation is “likelihood of confusion.” International community sites could easily be confused for the main WordPress project, as could sites selling plugins, themes, and other CMSs, but tutorials and books present a gray area. Similar sites in the Adobe community (photoshoptutorials.ws and photoshopessentials.com, for example) are not owned by Adobe, but are not seen as trademark violations.

Sherman Hu and Brandon Hong both received letters. As is often the case in the blogging world, a blogger wrote about it: in his post, Andy Beard remarks on Automattic's tardiness in registering the trademark and preventing others from using it. He also defends the two sites being singled out. Both provided WordPress services and cultivated their own communities; they weren't, he felt, the "spammy products" that Matt thought they were. Besides, just a year earlier, there had been a link farm on WordPress.org.

Others jumped to defend the two sites. Even those who supported Automattic's trademark position bristled when Matt branded the two sites as "snake oil,” and Hu's customers and friends flocked to Beard's post to voice their support. Other prominent internet marketers, including copyblogger's Brian Clark, took issue with the fact that long sales letters were branded spammy and scammy.

Eventually, the sites came to an agreement with Automattic. Sherman agreed to add a trademark symbol beside every use of the word WordPress, and Hong's WordPress Tutorials site came out with a redesign. Sherman eventually shut WordPress Videos down in 2008, moving on to focus on his consulting business.

Since then, Automattic has consistently enforced the WordPress trademark. While to many it appears that Automattic is motivated by commercial benefit, its involvement brings advantages as well; as commercial entity, it's able to put resources into enforcement that the free software project doesn't have. Still, it would be several more years before all the WordPress trademark issues were resolved.

24. Habari

Three years in, the project included developers, support forum volunteers, documentarians, and others helping out. Many had been around since the early days, and while the project and software had grown and changed, some felt that the governance structure had not. A free software project can be run in many different ways. WordPress has always had a Benevolent Dictator for Life (BDFL) structure: the final decision often rested with Matt, even if it was Ryan Boren who made and implemented most of the technical decisions. Some contributors, however, felt that the project could benefit from a committee structure, with a team of people driving the project’s direction and decision making. Others were unhappy with how Matt led the project, and left. The first major fork of WordPress didn't involve software; it was within the community.

Some of the unhappy contributors met in September 2006, at the Ohio Linux Fest in Columbus. They had lunch together at a Buca di Beppo. Among the diners were four WordPress developers -- Owen Winkler (ringmaster), Rich Bowen (drbacchus), Scott Merrill (Skippy), and Chris Davis (chrisjdavis). During lunch they talked about their grievances. The same story came up again and again -- patches were rejected because they didn’t fit the project's vision. The conversation kept returning to the possibility of setting up a new free-and-open-source (FOSS) project. By the time the meal ended, the developers had decided to stop talking and act: they would create a new blogging tool. A few weeks later at ApacheCon, they chose a name: Habari, which is Swahili for "What's up?" or "What's the news?" They created a governance structure and development ethos for the project, and started work in earnest.

Habari launched in January 2007, and many of its founding principles are in direct opposition to those of the WordPress project. The Habari Motivations page addresses the issues that the founding developers objected to in the WordPress project -- and explains their different approach to running a free software project. It also highlights some problems that were afoot in the WordPress project three years after its launch. Every free software project -- indeed every group or community -- has its problems, especially as it becomes established. Tensions that were ignored during the initial heat of enthusiasm become entrenched, and as enthusiasm fades, those tensions surface.

Governance style was one major issue. Many weren’t happy with the BDFL model, despite its prevalence in free software projects, from Linus Torvalds of Linux to Guido van Rossum of Python. A BDFL typically has final say about the project's direction and vision, but as a project grows, there are many people who wield influence and make decisions.

Rich Bowen, one of the developers who was dissatisfied with how WordPress was run, came from the Apache project. Apache has a committee model. The committee comprises developers and non-developers, all of whom have a say in how the project runs. Unlike WordPress, which requires that commits be approved by the committer and/or the patch reviewer, commits in Apache require consensus. Habari launched with a committee structure, much like Apache.

Designer Michael Heilemann was one person enticed by Habari. He’d designed the Kubrick theme and was looking for a new challenge after the Shuttle project failed before implementation.

Michael redesigned the Habari interface -- which he says was both a good and bad experience. He enjoyed designing and implementing it, less so getting it approved. Because of Habari's committee structure, a lot of time was spent discussing the new admin interface. People with no design background weighed in with opinions and everyone received equal weight. This left Michael feeling like he couldn't get his work done and he ended up leaving Habari. When asked whether he prefers a BDFL or an Apache-style model, he says:

It’s easy to end up in very long discussions if everybody has equal footing. And that makes for a great democracy, but it’s also very hippie, 60s, everybody gets to sit around and share their opinion, but that’s not always something that’s really worthwhile. You don’t actually, necessarily, get a better product out of it. And so often you need somebody with vision, or at least somebody with a point of view with opinion to weigh in.

The Habari Monolith interface, designed by Michael Heilemann.

Commit access was another flash point. In the Apache project, a clear path existed to gain commit access to the repository. That wasn't the case in early-2006 WordPress. Matt and Ryan acted as a funnel through which all code would be reviewed. More committers were eventually added, but it was a slow process and one that led to frustration, particularly among prolific contributors.

Coming from Apache, Rich Bowen brought a different perspective -- which he shared with other dissatisfied developers. For Rich, WordPress didn’t constitute a true meritocracy -- there was no opportunity for those with ability to gain power and responsibility. The final decision over who did and didn’t gain authority lay with the project’s leader -- it was entirely up to Matt's discretion. When Matt, in a discussion thread, said that WordPress is a meritocracy because commit access is provided to "the best of the best of the best contributors who prove their worth over time with high-quality code, responsiveness to the community, and reliability in crunch times,” Rich pointed out that because the final decision lies with the BDFL, the community can never become meritocratic.

At the heart of the discussion was a fundamental disagreement about how a free software project should be structured. In Homesteading the Noosphere, Eric Raymond discusses project structures and ownership, looking at how these emerge over time. WordPress follows Raymond's outline: the project had a single owner/maintainer (or rather two -- Mike Little and Matt Mullenweg). Over time, Matt assumed project leadership. In WordPress' case, commit access carried with it an implicit level of authority. Those with commit access are the arbiters of the code that ends up in core. Matt made clear on a number of occasions that he didn't "want it to be a status thing," but it still became one.

Matt posted to the mailing list in 2005, saying "Committing != community status. It simply is a way to ensure that all the code that goes into the core is reviewed before being distributed to the world.” But community members naturally ascribe more authority and trustworthiness to those with commit access. It was unclear what it took to become a committer or a lead developer. Instead, the roles developed organically. For the community, authority naturally followed commit access to the repository, and commit access followed high-quality code submissions along with an understanding of and commitment to the project ethos. Commit is a symbol of trust; with only two committers, it appeared that the project leads did not trust others in the community.

This had another consequence: non-code contributions went unacknowledged. Commit access may have been given out sparingly, but authority and leadership were still achievable in theory by anyone who could write code. For those who worked hard in support forums, wrote documentation, or provided translations (among other supporting activities), there was no formal way to progress, gain status, or be acknowledged. Coders receive props for code accepted into core, but there was no equivalent system for those who worked or contributed elsewhere. When there were rumblings of discontent, it wasn’t just coders who were complaining.

Habari’s approach was radically different. Commit access was achievable by anyone. The Habari motivations page says "Our contribution model is a meritocracy. If you contribute code regularly, you will be granted permission to make contributions directly (commit access).” The project takes this approach even further -- it isn’t just coders who received commit access. Owen Winkler, one of Habari’s founders, says:

There are some people who are committers, who are part of the primary management committee in Habari who I would never want to actually touch the code because they don’t really do development. But we give them access to it because they’ve demonstrated that they’re part of the community and they’re actively trying to advance Habari as a project.

In Habari, commit access is an explicit sign of trust and responsibility. If you're building a project in which the two do not go hand-in-hand, keeping commit access solely as a checking mechanism makes sense. The problem? If it’s not clear to people within the project what constitutes authority, commit access becomes one of its few indicators.