The Story of WordPress - Part 4

You are reading the fourth part of the series, find the whole series at series/wpbook.

25. Creating a Folksonomy

In the wake of the exodus to Habari, the project began to evolve. In March 2007, Robin Adrianse (rob1n) became WordPress’ first temporary committer when he received commit access for three months to help Ryan Boren address languishing trac tickets.

Also in March, the plugin directory launched. Before the plugin directory, developers hosted their plugins on their website. The directory gave them exposure to a huge number of WordPress users. Samuel Wood (Otto42) recalls how the plugin directory encouraged him to distribute his code. “I was writing them before, but I didn't give them to anybody. It encouraged me to release plugins because I had a place to put them.”

The WordPress Plugin Directory in 2007.

WordPress 2.1 had launched in January 2007, after a release cycle of more than a year. WordPress 2.2 was the first to adopt the new 120-day release cycle. This goal, which would later become codified as deadlines are not arbitrary in WordPress’ philosophy, was an ongoing challenge. It was tested in WordPress 2.2, which featured a new taxonomy system -- the biggest database architecture change to date. Developing in an open source environment means leaving time for every voice to be heard, waiting for volunteers with busy lives to get things done, and discussing new features and architectural changes. It’s a challenge that WordPress would have to address release cycle after release cycle.

In the early 2000s, the internet abounded with discussions about the best way to organize information. Content has metadata assigned to it, which can be used to organize and display information. Traditional web classification methods imposed a top-down categorization structure. A website created a category structure and users placed their content in the correct category. These structures were often rigid, forcing users to shoehorn their content into something that didn’t necessarily fit. A new method of classification emerged -- tags, a bottom-up classification form in which an index or a cloud can be generated based on keywords that the creator applies to the content.

Social bookmarking site Del.icio.us was the first to use tags. While Del.icio.us wasn't a bookmark management pioneer, its tagging system set it apart. Users tag the links they save, and the tags are then used to group together links in a user’s own collection and across the entire social network. Visiting the link http://delicious.com/tag/php displays all links tagged PHP.

The classification system in which users classify content themselves, creating mass tagging networks, became known as a folksonomy.

In 2005, Technorati, the blog search engine, launched its own tagging system. It enabled users to run a tag search across major platforms such as Blogger and Typepad, CMSs like Drupal, and other services such as Flickr, Del.icio.us, and Socialtext.

WordPress lagged behind, and there was pressure from both the free software and WordPress.com communities to add tags to the platform. WordPress’ native classification form is hierarchical, top-down categories. To interact with WordPress, Technorati picked up the “tag” from the WordPress post’s category. Many users found this unsatisfactory, as categories and tags are two different types of classification.

On his blog, Carthik Sharma wrote:

Categories can be tags but tags cannot be categories. Categories are like the huge signs you see on aisles in supermarkets – “Food”, “Hygiene”, “Frozen,” etc., (sic) they guide you to sections where you can find what you are looking for. Tags are like the labels on the products themselves.Categories and tags address two distinct use cases. Categories are more rigid, whereas tags are a lightweight way of classifying content. There was, of course, a plugin that did the job: WordPress users installed the Ultimate Tag Warrior plugin (though WordPress.com users could not).

In 2007, Ryan Boren opened a ticket to add tagging support to WordPress. Finally, WordPress would have tags. The next step was to identify the database schema.

A database stores all the content and data of a WordPress user. The database contains different tables from which data is retrieved. There is a post table, for example, which stores post-related data. The user table stores user data. Making changes to the database is not trivial. Any changes have to be done correctly because undoing them in the future can be difficult. Changes need to be performant. In a PHP/MySQL setup, increasing the number of database queries can slow the site down. The question arose: where should we store tagging data? Should it be in a new table? Or should it be stored in an existing table? Ryan proposed two database schemas. One of these created a new table for tags. Matt was keen on the second proposal -- putting tags in the categories database table. He believed it didn’t make sense to create another table identical to the categories table. In a comment on trac, he wrote:

We already have a ton of rewrite, API, etc. infrastructure around categories. Mostly I see tagging as a new interface to the data. On the display side, people want their tags listed separately from their categories, and probably something like a tag cloud function.Previously, WordPress had already successfully reused tables; for example, posts, pages, and attachments are all stored in the same table, and at that time, the categories table also contained link categories. Tagging, from a user’s perspective, enabled them to tag posts, display a list of tags, and display posts with the same tag. What was the point in duplicating the infrastructure when it could be achieved within the current table system?

Few developers supported putting tags in the categories table. Some believed the table would become bloated and argued that adding tags to it meant including additional code to keep the two taxonomy types separate. This additional code could introduce bugs, and make future maintenance and extension of the table difficult for developers.

On wp-hackers, April 2007 was spent discussing the new database schema for taxonomies. A suggestion that gained considerable community traction was splitting categories, link categories, and tags into their own individual tables -- but it was impossible to reach consensus.

After checking in the single-table taxonomy structure (changesets #5110 and #5111), Matt posted a new thread on wp-hackers making the case for using the categories table. He argued that:

- It would perform faster as no additional queries would need to be carried out to support tags. A separate tag table would require at least two extra queries on the front end.

- It would provide a better long-term foundation. Tags and categories would be able to share terms (for example the category “dogs” and the tag “dogs”).

- There were no user-facing or plugin-facing problems.

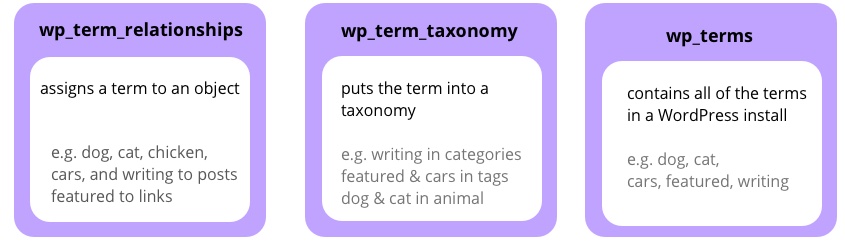

Ryan Boren proposed a compromise, one which enabled individual terms to be part of any taxonomy, while keeping the same ID. It was a three-table solution, with tables for terms, taxonomies, and objects. Discussion ensued, a new trac ticket was opened up, and a new structure was created based on this proposal. The first table, wpterms, holds basic information about single terms. The wptermtaxonomy table places the term in a taxonomy. The final table, termrelationships, relates objects (such as posts or links) to a termtaxonomyid from the term_taxonomy table.

The database structure for WordPress taxonomies.

This approach had the advantage of assigning one ID to a term name, while using another table to relate it to a specific taxonomy. It's extensible for plugin developers who can create their own taxonomies. It also enables large multisite networks, such as WordPress.com, to create global taxonomies -- unified tagging systems in which users of different blogs can share terms within a taxonomy.

Like many WordPress features, tags landed on WordPress.com before they shipped in WordPress. From the beginning, the new structure caused huge technical problems. The increase in tables meant that WordPress.com needed more servers to deal with the additional queries. “It was slower to be completely honest,” says Matt. “That was a cost that we saw in a very real way on WordPress.com, but also a hidden cost that we did impose on everyone who was doing WordPress in the world.”

More than just a challenging code problem, the taxonomy implementation highlighted problems in the development process. Heavy discussion meant development dragged on. Some wanted to delay the release. Some wanted to pull the feature. Others wanted to revise the schema in a subsequent version. Andy Skelton responded to the wp-hackers discussion:

To include a premature feature in an on-time release degrades the quality of the product. I refer to not only the code but the state of the community. Increments are supposed to be in the direction of better, not merely more. Better would be to release on time with a modest set of stable upgrades.The 120-day release schedule was in danger because of one issue. Making major architectural changes to core just weeks before a release was contrary to the aims of the new development process. A thread suggested delaying 2.2's release. The architectural changes were too important to be done in an unsatisfactory way.To block release while the one new feature gets sorted out would be a maladjustment of priorities. If 2.2 seems light on sex appeal, so be it. Better to keep the release date as promised.

Eventually, Matt decided to delay the 2.2 release, pull tags out of core, and bring in widgets -- a user-facing feature that would encourage people to update their version of WordPress.

Andy Skelton developed widgets for WordPress.com users; he built them to give bloggers more flexibility with their site's layout. Widgets are code blocks users can drag and drop into place through the user interface. They allow bloggers to add a calendar, a search bar, or some text (among other things) to a sidebar in any order they wish. It was a hugely popular feature on WordPress.com; the plugin for WordPress was also a great success. Launching widgets on WordPress.com meant that many different users could test them before they made it into core as a feature.

The new tagging feature finally shipped in WordPress 2.3 -- in a structure that was the outcome of extensive negotiating and haggling. This wrangling process has had consequences for WordPress developers ever since. Shared terms have had lasting implications for core developers, plugin developers, and users. The problem with shared terms is that an item could have multiple different meanings, but the database treats all of them identically. For example, the word apple. A developer creates the taxonomy “Companies” and the taxonomy “Fruit,” and the user places the term “apple” in both. Conceptually, this is a different item -- a company and a fruit -- and they appear in the user interface as two distinct entities. But the database treats them as the same thing. So if a user makes changes to one -- for example, capitalizing it -- changes are made to both.

In a post in 2013, Andrew Nacin wrote that, “Hindsight is 20/20, and shared terms are the bane of taxonomies in WordPress.” Each term is represented in two different ways. Since an individual term can appear in multiple taxonomies, it’s not straightforward to identify the actual term in the actual taxonomy that you want. It has become a challenge to build new features that use one identification method when there are parts of WordPress that use the other.

A case in point: to attach metadata to a term, there must be one object identifier. However, the public ID uses a different identifier. It is extremely difficult to target data consistently when it is identified in multiple ways. WordPress has a long-term commitment to maintaining backward compatibility, so creating a new schema isn’t possible. The effort to get rid of shared terms must progress step by step, over a number of major releases (this is being carried out over three releases in the 4.x series).

The over-engineered taxonomy system came about through argument and compromise. When the bazaar model works, it can produce software that people love to use. The model fails when intractable arguments result in compromises that no one is 100 percent happy with. The new taxonomy system did, however, contain one notable benefit. Neither of the original proposals for the taxonomy schema (putting tags into the category table, or creating a new table just for tags) would have allowed developers to create custom taxonomies, and the latter became a major element in WordPress' transition from a straightforward blogging platform to a bonafide content management system.

Even with these setbacks, software development continued mostly on schedule. Since tags were pulled from 2.2, there were only 114 days between WordPress 2.1 and 2.2, and then 129 days between the release of 2.2 and 2.3. While delays would recur in some future releases, there was nothing that resembled the long, dark year between 2.0 and 2.1.

26. Sponsored Themes

A community of hobbyists drove WordPress for a long time, but eventually, the hobbyists wanted to support their hobby. Developers charged for customizations; Automattic was building a blog network along with related products like Akismet. Theme designers, too, wanted to make money for the time and effort they put into developing themes for the project.

It isn’t immediately obvious how someone can make money and still uphold the ethos of a free software project. How can the two goals co-exist? In the early days of the WordPress economy, the distinction between freedom and free beer was blurry. Community members fumbled for answers: is it acceptable to make money with a GPL project? Who has the right to make money out of a project that belongs to its volunteers? How can one run a theme business when the core product is free?

The period between 2006 and 2009 was one of experimentation and discovery for businesses in the WordPress ecosystem. During these tumultuous years, the community wrestled with commercialization while the theme marketplace grew. WordPress users -- web users -- have always been concerned with their websites' look. As WordPress became more popular, many bloggers built their own themes and realized that they could generate income from them.

Themes lagged behind plugins for an official repository. For a long time, themes were hosted on themes.wordpress.net, an unofficial theme directory. Theme developers could simply upload their theme and users could browse the directory.

The WordPress Theme Viewer in 2007.

The system was susceptible to spam and duplicate themes. Some theme developers abused the system by downloading their theme multiple times, to boost their ranking and appear among the most popular search results. The Theme Viewer was at the center of the first big debate about themes.

Theme designers tried theme sponsorship as a way to make money from their designs. Designers often use a link to their website in their theme as a credit. Kubrick, for example, links to Michael Heilemann's website. Every site that installs the theme links to the designer's website. The number of incoming links to a website is a variable in Google's PageRank algorithm: the more incoming links, the higher the PageRank, the further up in Google's search engine results. If thousands (or even hundreds) of people install a theme, the designer can watch herself soar up Google's search results. If that link comes from a high-authority website, even better.

Designers soon realized the link doesn’t have to be to their own website. Links have an intrinsic value, particularly to internet marketers. With a link in a WordPress theme, marketers don’t have to approach individual sites to ask them for a link. All they have to do is pay a web designer to include it in their theme, release the theme for free, and soon hundreds of sites are linking back to their desired URL.

Theme sponsorship approaches varied. Sometimes, companies contacted well-known theme authors to sell links in their themes. Theme authors could also be proactive. Authors advertised and sold their themes on websites, others auctioned themes at Digital Point, or they simply offered links for sale. In those early days, once the sale was made, designers would promote the theme on different WordPress theme sites, including official sites such as the WordPress Codex, community resources like the WordPress Theme Viewer, and reputable blogs such as Weblog Tools Collection. These themes were often distributed with a Creative Commons 3.0 license, which permits free sharing and theme adaptation, provided the credit link remains.

Websites focused on making money online became aware of theme sponsorship. Tutorials and articles about theme sponsorship proliferated, and sponsorship became part of an acceptable link-building strategy.

Some theme creators published themes with visible text links but didn't tell their users about the link, others used PHP or CSS to hide the links, while others still made it very clear that the theme had been sponsored.

For those in favor of theme sponsorship, the matter was simply about being paid for their work. Why should they work for free? Selling sponsored links ensured they could create and distribute free themes, which benefited the whole community. They argued that designing a good theme takes time and that non-sponsored themes were inevitably of poorer quality than sponsored ones.

Sponsored themes quickly became prevalent, with even respected authors selling links in their themes. Many considered it a "great business model"; finally, a way to make money from WordPress! Besides, those who supported the model argued that the default WordPress blogroll contained links to all of the original developers of WordPress -- Alex, Donncha, Dougal, Michel, Matt, Mike, and Ryan -- all of whom were benefiting in Google's search results.

Others felt that themes.wordpress.net was becoming a spam repository. More than 50% of themes on the WordPress Theme Viewer were sponsored themes. These contained links to everything from iPhone repair services to gambling websites, and from web hosting to flower delivery. Some themes were uploaded multiple times with only minor changes, thereby increasing the number of links on the Theme Viewer. Critics of theme sponsorship -- many of whom were designers themselves -- said that the themes polluted the community. They weren't against theme designers making money, but they didn't want to see the WordPress community become a hive of spam and SEO tricks. Theme sponsorship had opened the floodgates to SEO and internet marketers.

Buying and selling links went beyond the WordPress community. A few years earlier, Matt Cutts, the head of web spam at Google, had explained how link-selling affected PageRank. Google's algorithm detected paid links, and while it wasn't foolproof, it worked pretty well. Paid links made it harder for Google to gauge a website's trustworthiness. As a result, Google took away that site's ability to affect search results:

Reputable sites that sell links won't have their search engine rankings or PageRank penalized – a search for [daily cal] would still return dailycal.org. However, link-selling sites can lose their ability to give reputation (e.g. PageRank and anchortext).

WordPress users who installed sponsored themes could be penalized for links that they weren't even aware they were hosting. And, hidden links could further reduce a user's PageRank. In a post in April 2007, Matt Cutts condemned hiding links in a website and asked web masters to disclose paid links.

There were plenty of themes that contained links that weren't sponsored. Designers would include a credit link to their website in the theme's footer. Designing and releasing a WordPress theme allowed designers to increase their profile on the web. Like internet marketers, their websites benefited from higher search engine results, and website visitors might click on the link, generating more business for the designer.

It was common at that time for a designer to release their themes under a Creative Commons license, which asks users to leave the credit link intact. In the middle of the sponsored link furor, one designer took the next step. Tung Do (tungdo) authored the popular WordPress resource WPDesigner.com, along with a number of WordPress themes. In April 2007, he announced he would release his themes under the GPL. "Despite that I'm just ONE theme designer and despite that I don't contribute directly the WordPress code (sic)," he wrote, "I believe that switching to GPL is a step in the direction to support the WordPress team and to help the WordPress theme community grow (positively)."

Weblog Tools Collection (WLTC) was the first website to take direct action against sponsored themes. At WLTC, designers submitted themes and Mark Ghosh, who ran the site, regularly wrote about theme releases. In April, Mark weighed in on sponsored themes. While he didn't condemn them outright, he did institute a new policy:

All themes with sponsorship links will be labelled as such when they are published, non-sponsored themes will be published first, and we require sponsorship disclosure to be made to us when authors make us aware of their new themes. If this disclosure is not provided and the theme has sponsored links, the author will be barred from being able to post their new themes on weblogtoolscollection.com until further notice.

The 166 comments Ghosh received highlighted just how divisive the issue was. Viewpoints ran to both extremes. Many users were unhappy about links being placed in their websites -- this was particularly concerning to people whose websites had a moral or religious bent. While users supported linking to theme authors, they weren’t happy that links for credit cards or flower delivery were being displayed on their website. Theme developers said that it was a way for them to fund themselves and the creation of free themes, and that they were sad to see it being abused.

A few days later, Matt followed Mark's lead and posted on WLTC about sponsored themes. He had become aware of the trend back in September 2006, when he had downloaded the Barthelme theme from plaintxt.org and discovered a link to a New York flower delivery service. For him, there were three main issues:

- that sponsored links negatively impact a user's Trustrank and that the user hadn't made this decision themselves;

- that sponsored themes are adware;

- that theme authors who sell links and release their work under a creative commons license contravene the GPL.

All of these factors meant a negative experience for WordPress users. While the project allowed people to make money from WordPress-related products and services, it didn't support methods detrimental to users. Whatever the original intentions of sponsored links, themes had become so polluted that they undermined the trust that a user had in the software and in the community. As a user-focused community, the project needed to regain that trust.

The argument that theme authors deserved to be compensated for their work held little weight when WordPress itself had been built by volunteers. There was no opposition to people making money from WordPress, but official project resources should only promote companies and individuals in line with the core project ethos.

Matt closed the post, linking to a vote on a proposal to remove sponsored themes from WordPress.org. The discussion on the thread has arguments for and against theme sponsorship; some voted for a complete ban, others for sponsored theme disclosure, while others felt theme designers should be allowed to include any links they want in their theme.

Whatever the results of the vote, the tide turned against sponsored themes. These were not looked upon favorably at WordPress.org, with sites and people who had promoted sponsored themes already banned from the forums. Even Matt Cutts weighed in, saying that he agreed 100 percent with Matt’s position on sponsored themes.

In July, Mark announced on WLTC that he would no longer promote sponsored themes, and shortly after, Matt announced that all sponsored themes would be removed from themes.WordPress.net. Despite a positive reaction from much of the community, there was a backlash, primarily directed at Mark and Matt.

Some theme developers saw theme sponsorship as a valid way of making money, and were angry about being branded as "unethical." This was particularly the case when they saw other theme developers behaving unethically, from downvoting other developers' themes and using sock puppetry to upvote their own, to stuffing themes with copious links to their website.

Despite the sponsored theme ban on official WordPress resources, link sales continue today. The Digital Point forums, for example, are filled with themes available for sponsorship. Theme sponsorship is not without its dangers. In 2012, a former theme sponsor posted on the Webmaster world forums about Google penalization for "inorganic" incoming links:

Some 2+ years ago in throws (sic) of questionable wisdom I sponsored about five or six WordPress themes where the "Designed by" link in the footer gets replaced by a link to your site. They were nice looking and "relevant" themes, at least as far as the name and pictures used in design suggest. They were not used much initially and I did not think much of them until these "unnatural links" notices started flying a month ago. Google confirmed that these links were the issue, but with the themes in the wild there wasn't a whole lot that the sponsor could do about it other than contact the websites using the theme and asking them to remove the link.

Sponsored themes were the first large-scale attempt at making money from WordPress themes. Custom design and development existed too, but link sales appeared to be a valid way of making money, particularly at a period when the web teemed with SEO experts and internet marketers on an unremitting search for ways to climb Google's search results. Sponsored themes brought WordPress, not for the first time, into proximity with SEO, both white hat and black hat. Selling links in a theme slipped easily into questionable SEO practices; it also turned out to be an unsustainable business model. With Google as the rule-maker, a simple policy change could wipe out an entire market. And as sponsored themes started to disappear from the community, theme designers and developers looked for new ways to support their hobby.

27. Update notifications

Peter Westwood became a core committer in July 2007, bringing the number of people who could commit code to four. Westi got involved in the project in 2004 while working as a software engineer -- he had written a script that downloaded WordPress and installed it on a server. He helped with the Codex, and found and fixed bugs. Like many other developers, he had little PHP experience when he came to the project.

The wp-hackers mailing list was in its third year, but productive discussion there diminished over time. More and more decision-making happened elsewhere. For example, in February 2007, Ryan integrated phpmailer with WordPress. The code was committed after a short discussion on trac. It wasn’t until September that a phpmailer conversation took place on wp-hackers -- one that few committers participated in.

Exchanges on the mailing list inclined less toward development, and more toward meta-discussions about the mailing list itself, from the high signal-to-noise ratio, to ideas to improve mailing list etiquette.

Andy Skelton wrote about the problem with wp-hackers:

There is just one thing I want to make clear about wp-hackers: a hacker is not someone who discusses or pays lip service or dissents or casts a vote or says what can or should be done. Hackers aren’t committee members. Hackers are more interested in proving what can be done than arguing about it.

There was too much talking and not enough hacking on wp-hackers, and opinion often swayed conversations rather than fact. Mailing lists can become dominated by people who have time to comment, rather than those doing the work. The latter might have the most valuable feedback, but they’re often too busy to keep up with a high-traffic mailing list.

WordPress isn’t alone in this phenomenon. A 2013 study of the Apache Lucene mailing list (PDF) found that “although the declared intent of development mailing list communication is to discuss project internals and code changes/additions, only 35 percent of the email threads regard the implementation of code artefacts.” As well as discussing development, mailing list participants discussed social norms and behavior. The study also found that project developers participate in less than 75 percent of the discussions, and start only half of them. Developers prefer to communicate on the issue-tracking software -- a finding resonant with WordPress, as developers ultimately switched from the mailing list to WordPress trac.

Mailing lists tend toward bike shed discussions, fn-1 a term derived from Parkinson’s law of triviality:

Parkinson shows how you can go in to the board of directors and get approval for building a multi-million or even billion dollar atomic power plant, but if you want to build a bike shed you will be tangled up in endless discussions.

An atomic plant is so vast that only very few people can grasp it. The board of directors assume that somebody has the knowledge and has done the groundwork. In contrast, everyone can build a bike shed, so everyone has an opinion on how it should be done, and especially what color it should be painted.

In his book Producing Open Source Software, Karl Fogel notes that as the technical difficulty of an issue goes down, the “probability of meandering goes up:”

...consensus is hardest to achieve in technical questions that are simple to understand and easy to have an opinion about, and in "soft" topics such as organization, publicity, funding, etc. People can participate in those arguments forever, because there are no qualifications necessary for doing so, no clear ways to decide (even afterward) if a decision was right or wrong, and because simply outwaiting other discussants is sometimes a successful tactic.

With its community growth and low barrier to entry, the WordPress project has been susceptible to bike shed discussions like any other free software project. A Google search for “bikeshed” on the wp-hackers mailing list displays the discussions in which someone has cried “bike shed,” as does a similar search on trac.

In 2007, for example, discussion about what to call links got heated. A member of wp-hackers asked, “Anyone know why it's still called Blogroll in admin, when it's called Bookmarks in functions (wplistbookmarks) and yet displays by default as a list of "Links" in the sidebar?” The original post, "Blogroll, Bookmarks, Links," generated a total of 79 emails on the mailing list alone, and the discussion spilled over to a trac ticket.

Of course, one person’s bike shed is another person’s bête noire, and there were times when wp-hackers was alight with community members who insisted on giving specific issues serious consideration. One such instance was in early September 2007, before the release of WordPress 2.3, which contained the update notification system. This system alerts users when a new version of WordPress or of a plugin becomes available to install. The system collects information about the WordPress version, PHP version, locale setting, and the website’s URL from a user’s site, and sends it back to http://api.wordpress.org. A further piece of code carries a plugin update check, which sends the website’s URL, WordPress version, and plugin info (including inactive plugins) to api.wordpress.org.

For some, the data collection appeared contrary to the free software project ethos. They thought that collecting the blog URL was unnecessary. A ticket on WordPress trac requested that update checking be anonymized. Others had no problem with WordPress collecting the data, but were unhappy that WordPress did not disclose it. A number of people who didn’t oppose the changes nevertheless felt that there should be a way to opt out, so that users who required complete privacy would be able to turn off data collection.

This debate goes to the heart of one of WordPress' design philosophies: decisions, not options. This idea is heavily influenced by a 2002 article written by GNOME contributor Havoc Pennington. Many free software user interfaces cram in options so that they can be configured in multiple ways. If an argument ensues in a software project about whether something should or shouldn’t be added, a superficial solution is to add an option. The more options one adds, the more unwieldy a user interface becomes. Pennington writes, "preferences have a cost [..], each one has a price and you have to consider its value.” He outlines the problem with too many options:

- When there are too many preferences it’s difficult for a user to find them.

- They can damage QA and testing. Some bugs only happen when a certain configuration of options is selected.

- They make creating a good UI difficult.

- They keep people from fixing real bugs.

- They can confuse users.

- The space that you have for preferences is finite so fill it wisely.

WordPress developers carefully consider the introduction of any new option, and have become better at it over time. When the data collection question arose, they were extremely reluctant to introduce new options. Westi posted to wp-hackers:

One of the core design ideas for WordPress is that we don't introduce options lightly. The moment you think of making a feature optional you challenge the argument for introducing the feature in the beginning.

What benefit would an opt-out button for update notifications provide to users? The purpose of the notifications is to help users to stay up-to-date and secure. Adding an option to opt out of update notifications would only reduce the number of people who updated their sites, and increase the number of insecure instances of WordPress. The benefit to adding the option didn’t outweigh the cost.

Consequently, and despite the extensive discussion on wp-hackers, WordPress 2.3 was launched as planned, with the following note in the announcement post:

Our new update notification lets you know when there is a new release of WordPress or when any of the plugins you use has an update available. It works by sending your blog URL, plugins, and version information to our new api.wordpress.org service which then compares it to the plugin database and tells you whats (sic) the latest and greatest you can use.

The project also published the first version of a privacy policy on WordPress.org.

Amid these discussions, the project structure changed when Peter Westwood and Mark Jaquith became lead developers. The announcement post describes them as “a few old faces who are taking on bigger roles in the community.” Both were active committers who had taken on greater leadership roles. Both had participated in many of the more challenging discussions in the community, and they didn't always agree with current project leadership. They both, for example, opposed Matt’s proposal for the taxonomy structure, and Mark was one of the people who voiced concerns over data collection in WordPress 2.3. They added new perspectives to the project leadership: for the first time since the early days of the project, there were people other than Matt and Ryan to help guide and shape development of both the software and the project.

28. Happy Cog Redesign

Shuttle had failed back in 2006 and WordPress' admin still needed a redesign. Matt turned to design studio Happy Cog. Jeffrey Zeldman, Happy Cog founder, led the project, along with WordPress' logo designer Jason Santa Maria and UX designer Liz Danzico.

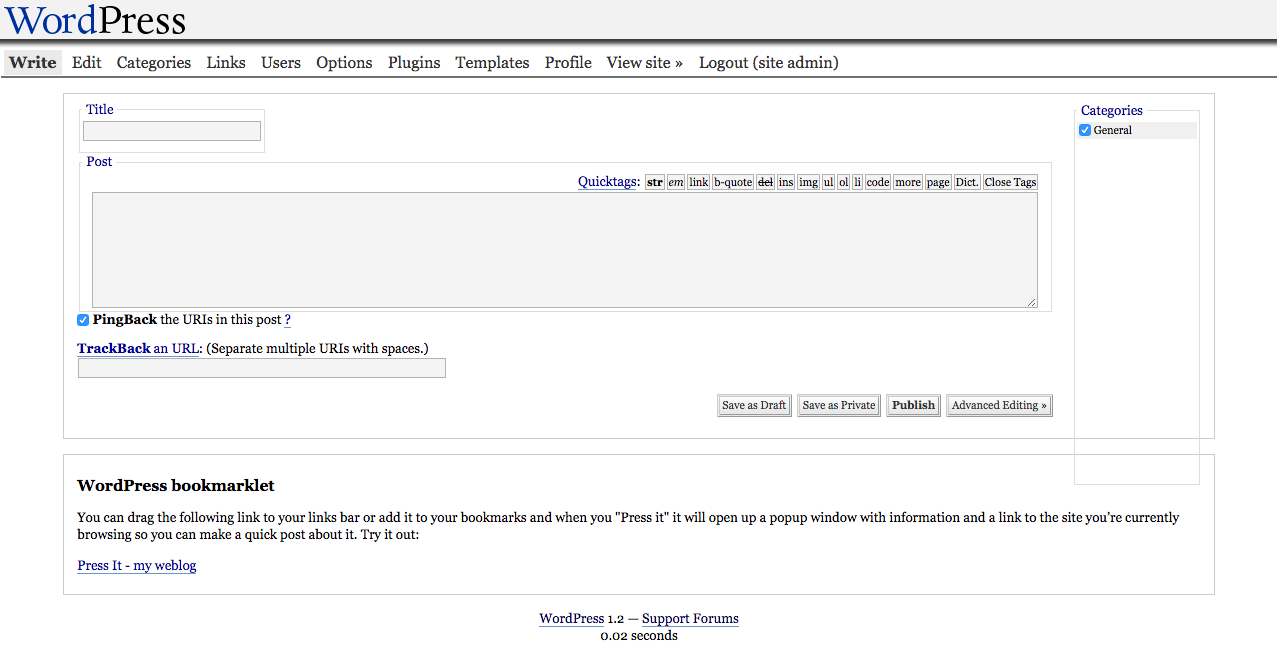

Whereas Shuttle focused on aesthetics, Happy Cog identified and corrected information architecture problems, and updated and improved WordPress' look and feel. Despite the project's user-first ethos, the admin screens had become cluttered, as new features were sometimes added in a haphazard way. The change between WordPress 1.5 and WordPress 2.3 speaks for itself.

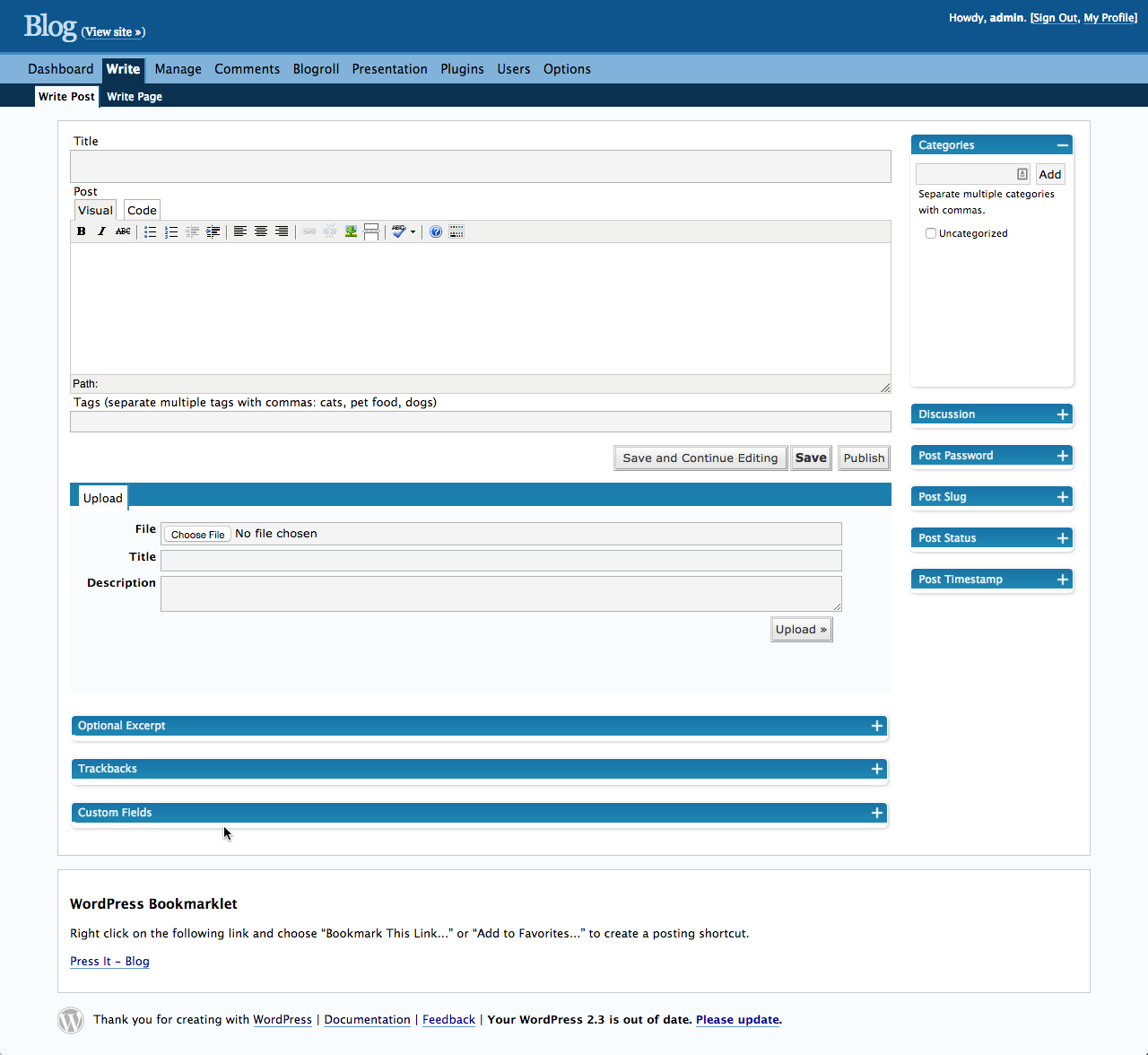

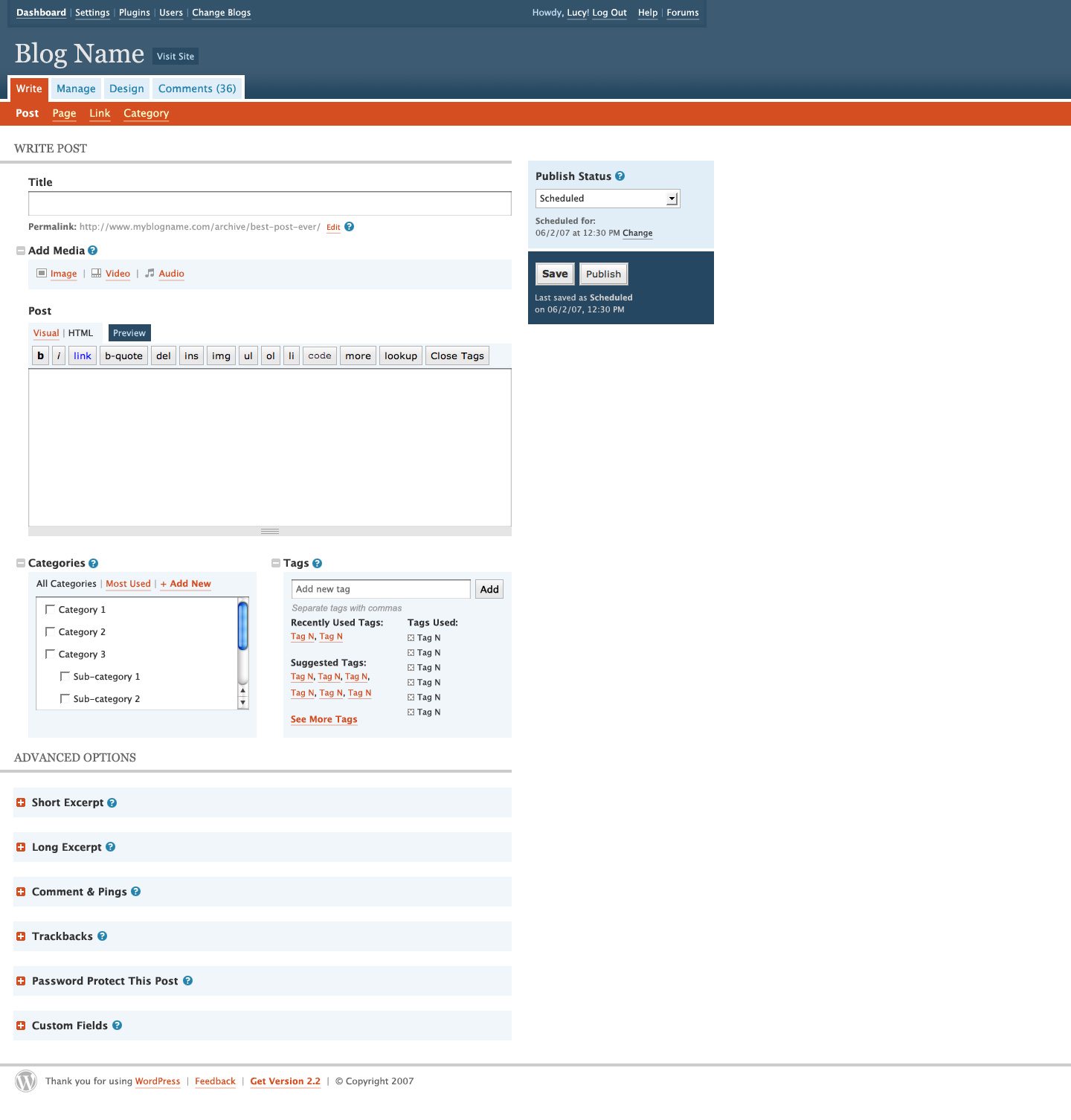

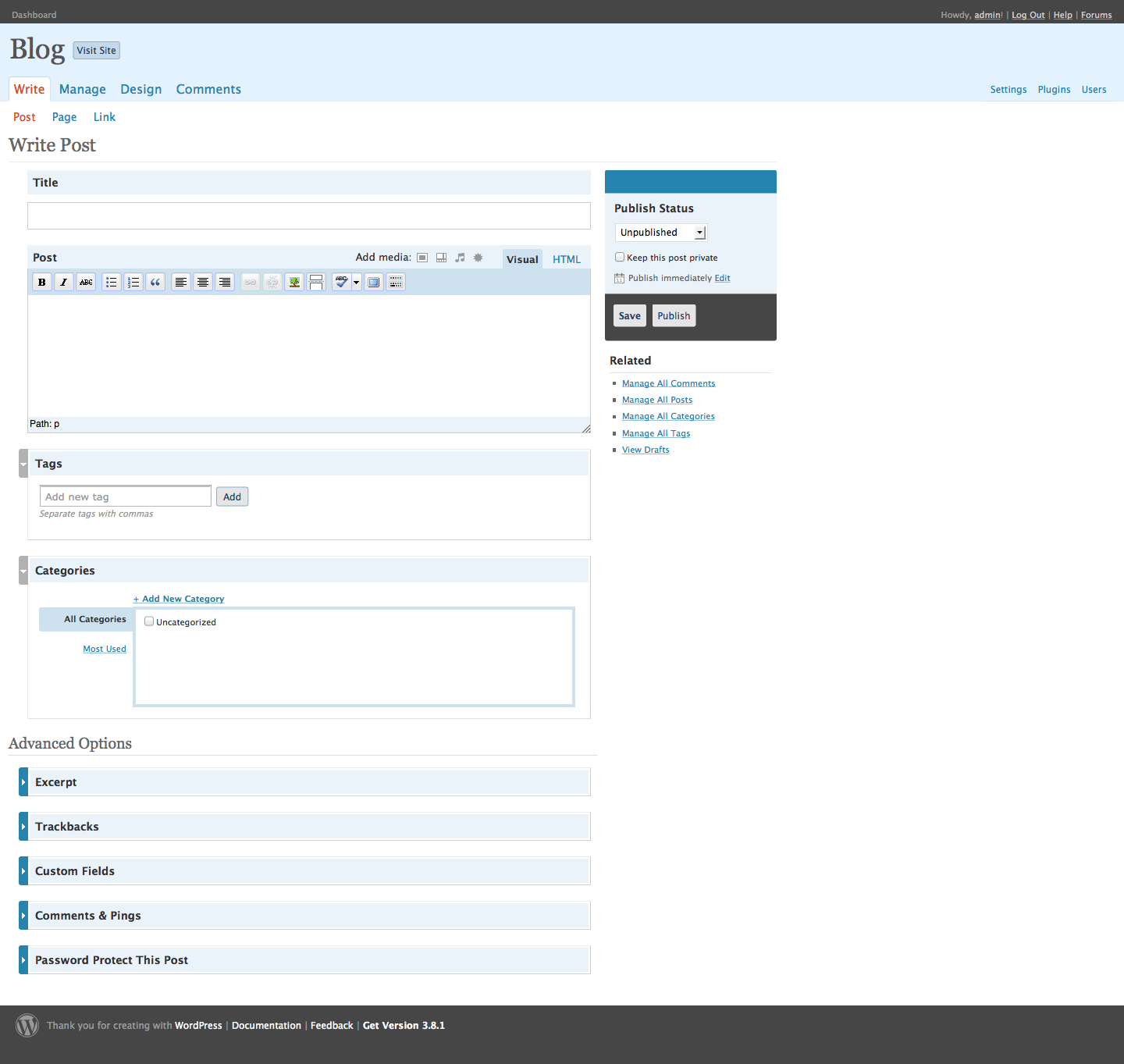

The Write screen in WordPress 1.5.

The Write screen in WordPress 2.3.

Happy Cog produced designs that WordPress developers then coded. The project included user research and an interface audit to identify WordPress' strengths and weaknesses, and to inform new structural and interface designs.

WordPress, as a free software project, was an unusual client for a traditional design agency. Matt and Jeffrey formed a buffer between the Happy Cog team and the community, but the designers, nonetheless, knew this was an entirely different type of client. Jason Santa Maria says:

Any other client will have customers and their own community, but you really have to just manage the people inside of a company, whereas when you’re dealing with an open source project, you deal with the people that you’re talking with, but there’s this whole gamut of other people that you will only ever get to talk to a small portion of. I think that that’s really difficult.Plus, I think that on an open source project like this, it’s inherently different, not just because it’s more of a CMS than an informational website -- the design needs are different -- but it’s just a different kind of way to work, knowing that whatever you do probably isn’t going to stick around for very long. It’s going to continue to evolve and continue to be adapted. Usually, in the very near-term as well, not even three-four months from now, but next week.

An audit and usability review were among the first steps. Liz Danzico researched and produced a 25-page document on WordPress. WordPress needed an admin that didn’t intrude on the user. In the audit, she quotes Mark Jaquith: "That’s when I know WordPress is doing its job: when people aren’t even aware they’re using it because they’re so busy using it!"

Liz spoke to Mark Riley, whose support forum experience gave him direct access to users' complaints. One of the major problems he highlighted was the clutter that had amassed in the Write screen between WordPress 1.2 and WordPress 2.0. Features had been added and then tucked into modules using the pods introduced by the Shuttle project. There were many actions a user could take on the Write screen, and many of them were confusing or hidden.

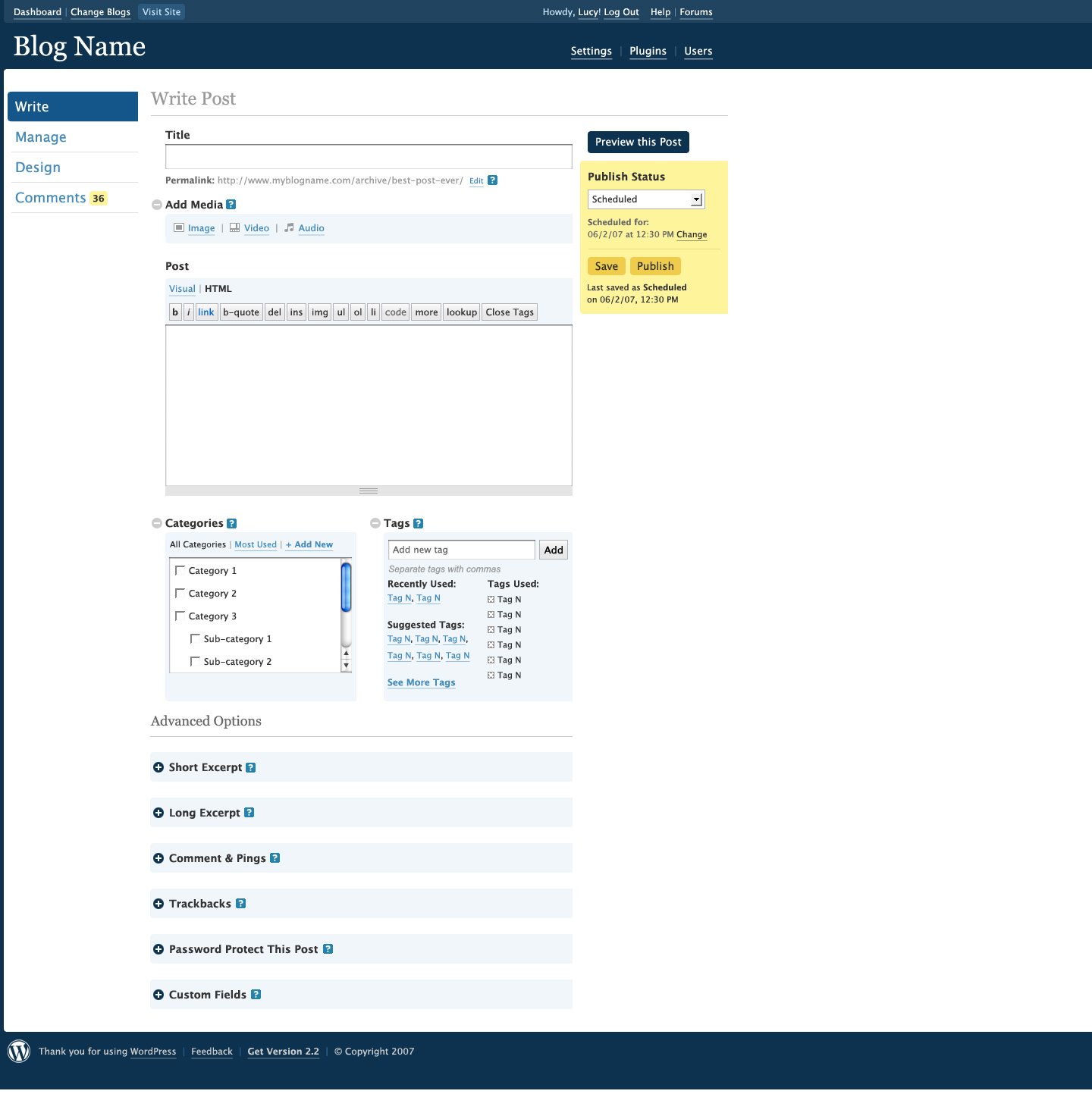

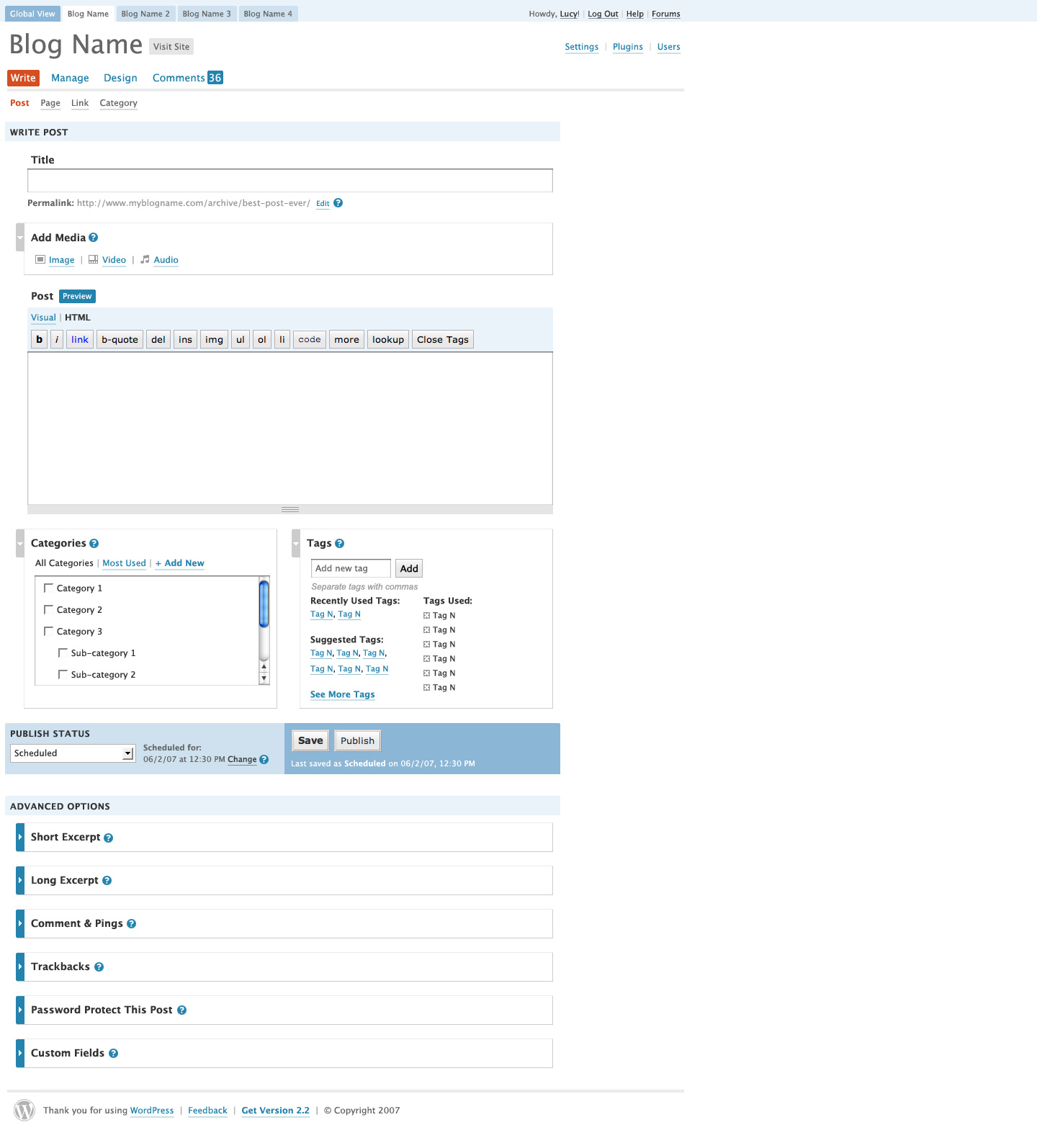

Discussion focused on navigation structure: labelling, position, and functionality grouping. Should they go with an object-oriented navigation (Posts, Pages, Comments, etc.) or an action-oriented navigation (Write, Manage, etc.)? Liz's first hunch -- supported by the newly launched Tumblr -- was that users preferred navigating by nouns. She felt WordPress’ verb structure was confusing. The first navigational structure iterations introduced both a noun version and a verb version. In the end, however, and after limited user testing, the team went with a mixture of nouns and verbs: Write, Manage, Design, Comments. This meant that the functionality for different content types was scattered over different menu items -- to write a post, for example, users would go to "Write." To manage the same post they would navigate to "Manage."

Happy Cog provided extensive and detailed proposals and research for WordPress, and shared them with Matt. Their reports display a sensitivity to web users, and an appreciation for simplifying and streamlining WordPress.

When it came to the design stage, Jason Santa Maria created three designs to present to Matt, who would choose one to move forward.

He designed three early mockups:

Mockup Number 1.

Mockup Number 2.

Mockup Number 3.

Matt chose the visually lighter design. Jason had taken Shuttle's heavy blue palette and lightened the interface. An orange accent color complemented the lighter blues.

When the design was finally signed off, WordPress trunk started to transform. As changes took place, community feedback was posted to wp-hackers. Was the admin actually more usable? Major changes broke familiar patterns. Some comments compared the design to Shuttle's; a few community members even wanted to implement Shuttle's interface.

Just before release, a sneak peek was posted to the development blog, and WordPress users installed the release candidate to get a better look. The response echoed that of the rest of the community. Regular WordPress users were surprised by the functionality changes to the Write screen. For some, it was a step backward.

The Write screen in the WordPress 2.5 admin.

WordPress 2.4 was the first version to fall significantly behind the 120-day release cycle. Versions 2.2 and 2.3 were mostly on schedule, but the Happy Cog redesign brought in major changes to the codebase. Rather than just delaying release, a version was skipped, moving straight from WordPress 2.3 to WordPress 2.5, which was scheduled for release in March.

But there were bigger problems with this release cycle than just the delay. The community felt that they had not been consulted; they felt disenfranchised. In some ways, the redesign was destined to fail before it even began. With no participation and no process, there was no way to ensure community buy-in. Jeffrey Zeldman, reflecting on the process, says:

It worked for us, from our perspective, that we were a small team reporting to a single client who had life or death approval over everything. We had to please one user: Matt. He could say yes or no. We completely bypassed the community. That enabled us to get a design done that we felt was crisp and focused and achieved certain goals. And that sounds great. Except that, because the community wasn't involved, inevitably, the design then became unpopular because nobody got their say in it. And if I could go back and do it again, I would involve them up front, and find ways to get my feedback without it turning into a committee clustercuss.

As with Shuttle before it, problems surfaced in the design process. Free software projects are collaborative enterprises; when part of the process moves behind closed doors to avoid the problems of working by committee, new problems arise. However much a project tries to avoid it, that committee exists and must have its say.

29. Premium Themes

In the wake of sponsored themes, theme developers were looking for ways to make money. Some made money from customizations, but increasingly, people wanted to make money with WordPress products rather than with services. Why build one site when you can build one theme and sell it multiple times? If theme developers couldn’t sell links, they could do the next best thing -- sell themes directly to WordPress users. There was, however, some hesitation around this. When the project removed sponsored themes from official resources, people interpreted this in different ways:

"WordPress doesn't support sponsored themes."

"WordPress doesn't want me to make money."

"Automattic doesn't want me to make money.”

Some people felt that Matt only wanted Automattic to make money from WordPress, a situation that wasn't helped when, after the sponsored themes debate, Matt announced a WordPress.com theme marketplace, resulting in cries of hypocrisy. Despite laying the initial groundwork, Automattic decided not to go ahead with the plan. "It didn't seem right to go into it when we hadn't really worked out all the licensing issues yet," says Matt. fn-2

While the WordPress.com theme marketplace was set aside, employees inside Automattic were still curious about whether people would pay for a blog design. Noël Jackson (noel), a former Automattic employee, recalls the time when premium WordPress themes started to appear:

It was interesting, especially in the beginning when it started happening. It was interesting to see revenue figures for themes that were released as a premium theme -- not a WordPress.com premium theme -- but someone selling their theme and keeping the GPL license and thinking, "Well, people are actually buying this." There wasn't an issue with it. I think that made everybody happy.

Bloggers who used WordPress dabbled with making themes. They released them for free. “A funny dynamic happened,” recalls Cory Miller (corymiller303), the founder of iThemes. “People started hitting my contact form and saying will you customize this, or will you do this theme, or will you do all that stuff, and I was like I’m, I’m kind of a fraud here. And so I started charging for my work.” This is the familiar tale that some of the most prominent WordPress business founders tell today. Many of the people who run these businesses started out simply by making themes. These were often accidental businesses, with accidental businesspeople -- people who came to the community to scratch their own itch and found themselves inundated with requests for help, support, and customizations.

Although sites like Template Monster sold WordPress themes as early as 2006, the last quarter of 2007 saw the first surge in WordPress premium theme releases from within the WordPress community. Brian Gardner's Revolution -- one of the first premium WordPress themes -- launched in August 2007. A few weeks after, Tung Do released Showcase. Later that year also marked the launches of Proximity from Nathan Rice, Solostream from Michael Pollock, Cornerstone Theme from Charity Ondriezek, Premium News Theme from Adii Pienaar, and PortfolioPress from Magnus Jepson. Early the following year, Chris Pearson released Thesis.

Most of the theme vendors followed a similar path: from blogger to hobbyist themer. From releasing a free theme to testing the brand-new market. Few had career aspirations -- these were side projects to make them money in their spare time. Some also did independent development for clients. But the idea that selling WordPress themes could be big business didn't cross their minds. "Even when I quit my job to spend more time working on these themes," says Adii Pienaar (adii), co-founder of WooThemes, "and eventually rebranding and calling that effort WooThemes, I still thought that I was going to build a business around the custom design/development stuff, around consulting."

Theme sellers weren't sure how to price and license their themes. There was no community consensus about licensing and nothing clear from the project. Theme authors created their own license. A common model was offering a single-use license to use a theme on one site, and a developer or bulk license to use a theme on more than one site. These licenses restricted the number of sites on which a theme could be installed, and what the user could do with a theme. Some, for example, required that the user retain the author credit in the theme, which enabled the authors to charge users to remove the attribution link.

Users downloaded a free theme at no cost, or paid for a premium one. The label “premium,” however, implied that paid themes were intrinsically better, as though attaching a price tag elevated premium themes above free (and theoretically inferior) themes.

These commercial themes were often branded as “premium themes,” but there was little consensus about what made a theme “premium.” When Weblog Tools Collection (WLTC) asked, "What Makes a WordPress Theme Premium?," responses from community members were varied: "better documentation and support," "less bloggy," "better design," "better features," "better code," and "more functionality." Several people argued that money was the only difference between free and premium themes.

What distinguished designers and developers making free and premium themes was the time and effort they put into them, and the level of effort required to set them up. In an interview in June 2008, premium theme developer Darren Hoyt talks about the differences between creating a free and premium theme. He outlines his considerations:

- That hand-coding and tweaks to the files should be minimized with the inclusion of a custom control panel.

- That users shouldn’t have to download plugins so all theme functionality was bundled with it. "We tried to make Mimbo Pro more than just a theme or 'skin' and more like an application unto itself."

- That best practices for commenting code, valid markup, and well-written CSS are followed.

- That documentation be provided and evolve.

- That buyers get ongoing support and interactions with the developer.

Brian Gardner, designer of Revolution, said in a March 2008 interview that for him, a premium theme differs in how the site looks and acts. "If people respond to a site and say 'wow, I can't believe WordPress is behind that,' that's what premium themes are all about."

Attitudes varied widely between users, developers, and other community members. The user who interviewed Brian Gardner was a keen Revolution advocate. He commends the guaranteed support, comfort, safety, and the feeling that he's being looked after. A price tag doesn’t necessarily equate to these things, but some premium theme developers make customer support a priority -- and their theme sales rise. WordPress was no longer confined to the world of personal blogging. Businesses, particularly small businesses, used WordPress to build their websites. Paying a small fee for peace of mind was a worthwhile trade-off; it brought the promise of ongoing support. A free theme came with no guarantees.

Some theme developers were frustrated by premium theme sellers. "'Premium,' when it comes to WordPress themes," writes Ian Stewart in 2008 (iandstewart), "simply means 'it costs money' and not 'of superior quality.'" The false dichotomy set up by the "premium" label undervalues themes released for free. Justin Tadlock (greenshady) released the Options theme to prove that there was nothing to stop developers from releasing a free theme fully packed with bells and whistles. He was one of the first to explore an alternative business model, setting up his own theme club. In contrast to theme sales, he wanted to create a community around theme releases and support. Later that year, he launched Theme Hybrid.

The issue of whether someone should be selling themes wasn’t clear-cut. Some thought that you had to choose: you could either be involved in the community, or make money selling themes or plugins.

In a discussion on a wp-hackers thread from March 2008, the author concluded that a person either focused on making money or contributing to the community. But Mark Jaquith pointed out that the two aren’t mutually exclusive: it’s possible to make money with WordPress, while still making a positive contribution to the project. In the same thread, Matt outlined how he saw businesses best interacting with the WordPress community:

A GPL software community is like the environment. Yes you could make profit building widgets in your widget factory and not pay any heed to the forests you're clearing or the rivers your (sic) polluting, but in a few years you're going to start to deplete the commons, and your business and public perception will be in peril...Contrast that with sustainable development, with giving back to the community that sustains (and ultimately consumes) your services and you have the makings of something that could be around for generations to come.

Matt didn't see the premium theme market as in step with the community. He proclaimed premium theme sellers were in "murky waters," pointing out that there wasn’t much money in the enterprise. In a 2009 conversation with Ptah Dunbar, Matt said that he didn't like where premium WordPress themes were going, and that the premium theme market wasn't helping the community to grow.

Whatever the community's perception, users pay for themes, and companies that sell themes make money. Take ThemeForest, for example. The marketplace sells themes and templates for WordPress and different CMSs, as well as HTML templates. Upon launch in September 2008, ThemeForest sold mostly HTML templates; WordPress themes were 25% of sales. By September 2009, WordPress themes were 40% of all ThemeForest sales. In 2013, WordPress themes were 60% of all sales.

The discussions weren’t just focused on whether people should make money from WordPress. A bigger question was: how should themes be licensed? WordPress itself is licensed under the GPL. The GPL's copyleft distribution terms ensure that distributions and modifications of the software carry the same license. Derivative works also carry the license. Is a theme derivative of WordPress? There were arguments for and against, speculation, and opinion -- much of which was based on interpretations (or secondhand interpretations) of the license. Court cases are rarely fought around the GPL. Those that come close are often settled out of court, as with the Free Software Foundation vs. Cisco lawsuit, which happened at the same time as the WordPress community's debate over WordPress themes. The community was divided into two camps -- those who thought themes didn't have to be GPL, and those who thought they did.

There are a number of different factors, and one is whether a WordPress install and its theme is an "aggregation" or a "combination." The GPL FAQ distinguishes between the two: an aggregate means putting two programs side by side (like on a hard disc or a CD-ROM). People who thought that themes don’t have to be GPL argued that WordPress with a theme is an aggregate. They believed that a theme modifies the output of WordPress, but doesn’t necessarily engage with its internals. WordPress core developers, however, stated that themes use WordPress core internals. For a theme to be completely independent, it would need to use none of WordPress' internal functions.

For those who accepted that PHP was linked with WordPress in such a way that the theme inherited the GPL, there was still another possibility: distributing with two licenses -- which is what people often refer to as a "split license" -- or what Matt described as "packaging gymnastics." While the PHP in a WordPress theme works with WordPress internal functions, the CSS, JavaScript, and images do not. Therefore, a theme developer can package their theme with two licenses: one for the PHP and one for the other files. For theme authors concerned about piracy and copyright, this protected their intellectual property, while ensuring they followed the letter of the GPL. For the project, however, this was simply an evasive game that did an injustice to the spirit of the GPL.

Piracy was a major concern for many theme authors. They worried that anyone could buy their theme, legally distribute it, and even sell it. Putting a proprietary license on a theme, however, doesn’t stop people from distributing them. Themes from commercial sellers cropped up on torrent sites all over the web and were sold on forums such as Digital Point for a cut price. It was easy, if a user wanted, to download a commercial theme for free (though it often came loaded with additional links and malware).

Other fears were around making money. How could a business make money by selling a product that the buyer had a right to give away -- or even sell themselves? Designers and developers were reluctant to distribute with a license that they thought would damage their business. While Matt suggested they look into doing custom development, theme sellers were interested in selling products. It's more immediately obvious how you can scale a business selling products than with services. After all, if you don't factor in support and upgrades, it's possible to sell a digital product ad infinitum, creating a relatively passive income for yourself. Time and resources constrain doing custom design or development for clients.

Revolution was the first theme to be distributed with a 100% GPL license. Brian Gardner, Revolution’s developer, has a typical theme developer story -- he started as a tinkerer, did some contract work, started to sell themes, and realized he could make a business out of it.

Developers often came to the project with an implicit awareness of the free software and hacker ethos; they were comfortable with sharing code. Theme sellers came through another route: first they were bloggers, then tinkerers, then designers. As opposed to developers, theme sellers believed they had to protect their designs. "I and others that were starting to sell themes at that point wanted to protect our work," says Brian. "We were almost scared of the open source concept where the design and images and the code we felt was all ours and really wasn't derivative of WordPress itself so we sold things on a proprietary level."

Matt's ThemeShaper blog comment made Brian reconsider his stance. Matt wrote:

I'm happy to give significant promotion to theme designers who stop fighting the license of the platform which enabled their market to exist in the first place, just email me.

This was the encouragement that Brian needed. He emailed Matt to tell him he was interested. Before making the switch, Brian flew to San Francisco with fellow theme author Jason Schuller to talk to Toni and Matt. They discussed why theme sellers were using proprietary licenses and their fears around piracy. Matt and Toni made it plain: they were happy for theme sellers to make money, but themes needed to be GPL. In all of the confusion around the GPL, the message had become mixed. Theme sellers thought that they were expected to give themes away, not just that they were expected to distribute themes matching WordPress' principles of freedom.

A few days after the meeting, Brian announced that in the future, Revolution would be GPL. Jason Schuller followed suit.

In the midst of these debates, themes found a new home on WordPress.org. The theme viewer that had been hosted on themes.wordpress.net was riddled with problems: themes had security holes, and many of them had obfuscated code. The system was continually being gamed, there were duplicate themes, and many contained spam. The theme directory on WordPress.org was set up to rectify this; it was a place developers could host their themes, and where users could find quality WordPress themes. In July 2008, the Theme Directory launched on WordPress.org, using bbPress (which, at that time, was not a plugin), making it easier than ever to distribute free themes.

<img alt=“the first version of the WordPress theme directory“ src="/wp-book/images/29/theme-directory-2008.jpg" />

The WordPress Theme Directory in 2008.

fn-1 The notion of a bike shed was popularized in FOSS projects by Karl Fogel. In his book, Producing Open Source Software, he reprints an email from Poul-Henning Kamp to the FreeBSD mailing list with the title “A bike shed (any color will do) on greener grass…,” in which Kamp uses the “painting the bikeshed” analogy to describe discussions on the mailing list.

fn-2 The theme marketplace didn't launch until 2011, four years after the initial announcement.