The Story of WordPress - Part 5

You are reading the fifth part of the series, find the whole series at series/wpbook.

30. Riding the Crazyhorse

According to Ryan Boren, WordPress 2.7 ushered in “the modern era of WordPress.” It also brought a new face to the WordPress project. WordPress 2.5's redesign wasn't well received, though the reasons why weren't clear. Was the user interface the problem? Or did people dislike it because they felt cut out of the process?

Jen Mylo (jenmylo)fn-1 and Matt are old friends. At the time, she ran a usability testing and design center at a New York agency in conjunction with Ball State University. The center's usability studies used the latest eye-tracking technologies with clients, including television networks such as ABC, NBC, and MTV. When a TV network missed a usability test window, Jen offered the slot to WordPress at cost.

The usability review had three stages conducted in two rounds. In Round 1, they tested WordPress 2.5, gathering "low hanging fruit" recommendations to improve the admin's UI. Using the recommendations, the development team created and tested a prototype (Test1515) to learn whether users' experiences had improved. In Round 2, they created and tested a more drastic prototype -- dubbed Crazyhorse fn-2 -- based on the Test1515 findings.

The research team used three main testing methods in Round 1:

- Talk-aloud, in which participants are asked to think aloud as they carry out tasks.

- Morae screen activity and video recordings, which allow researchers to watch participants remotely.

- Eye-tracking technology to identify granular problems.

Twelve participants tested WordPress' admin. In Round 1, despite finding WordPress generally easy-to-use, the researchers identified several problems, including:

- Verbs vs. nouns: users found it difficult to conceptualize tasks because they weren't action-oriented (Write/Manage). Instead, users perceived content in a more object-oriented way. (Posts, Pages, Comments, etc.)

- Users didn't spend time on the dashboard. They used it as an entry point for other pages.

- The write post screen caused problems for users. Tags and categories appeared below the fold; some participants forgot to add categories and tags before publication -- returning to the post screen to add them afterward.

- The comments screen was confusing. Users didn't understand that they had to click on a commenter's name to edit a comment; they looked in the wrong place when asked to move a comment to spam.

- The difference between uploading and embedding media in the media uploader confused users.

Round 1 testing on WordPress 2.5 uncovered minor issues with settings, the media library, link categories, and tag management. Users also wanted more control over dashboard modules and the post edit screen.

In addition to a laundry list of small interface issues that presented simple fixes, such as changing comment author links, we were faced with larger issues such as the desire for user-determined hierarchies on long/scrolling screens, ambiguity in the Write/Manage navigation paradigm, and a disconnect between the act of adding media to a post and the ability to manage it. -- Usability Test Report (PDF)

Minor changes were incorporated into the Test1515 prototype and tested -- though they were so minor that participants didn't react strongly either way. The team created Crazyhorse to:

- maximize vertical space,

- reduce scrolling,

- increase access to navigation to reduce unnecessary screen loads,

- enable drag and drop on screens that would most benefit from user control, and

- redesign management screens to take advantage of natural gaze paths.

Jen and Liz Danzico -- who continued to work on WordPress’ usability in the Crazyhorse project -- created the design for the prototype. They sketched multiple ideas: front-end editing, accordion panes, and a top navigation. They chose the simplest prototype: a left-hand navigation panel, similar to Google Analytics and other web apps.

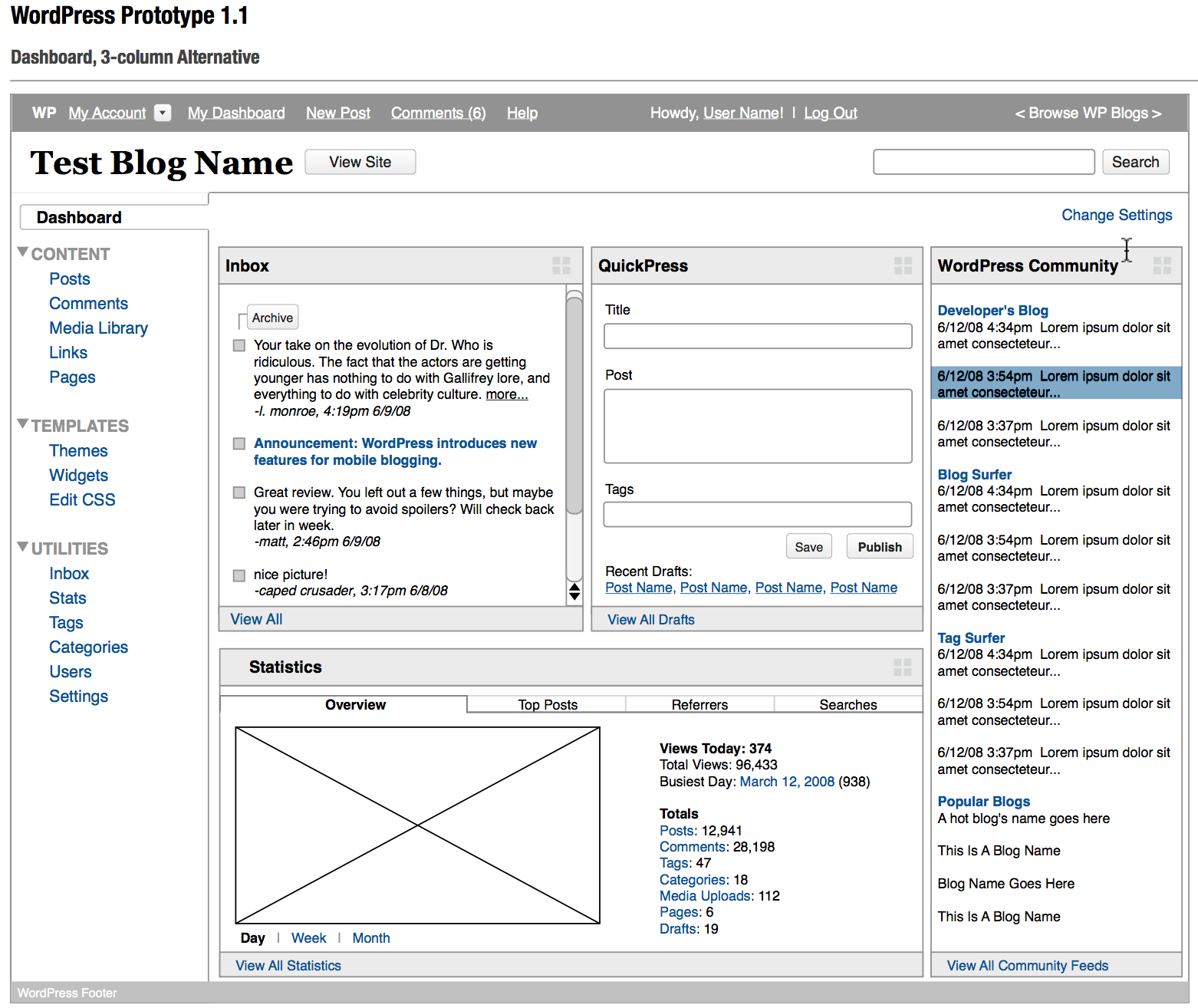

The Dashboard in the Crazyhorse prototype.

WordPress developers built the Crazyhorse prototype in a Subversion branch, based on the prototype document (PDF), which outlined changes and rationale. The project focused on user experience and functional development, so the prototype retained WordPress 2.5's visual styles. As in Round 1 testing, participants carried out tasks; talk-aloud, Morae, and eye-tracking helped assess results.

Most participants preferred Crazyhorse over WordPress 2.5 and every new feature tested provided actionable information for the next version of WordPress.

Participants loved the navigation on the left-hand side of the screen. They also preferred the object-oriented approach to organization. (Posts, Pages, Media, etc.)

Participants thought the Crazyhorse dashboard was more useful, and people appreciated the ability to customize it. They liked QuickPress, though they weren't sure if they would use it. With action links beneath comments, users found it easier to edit and moderate them.

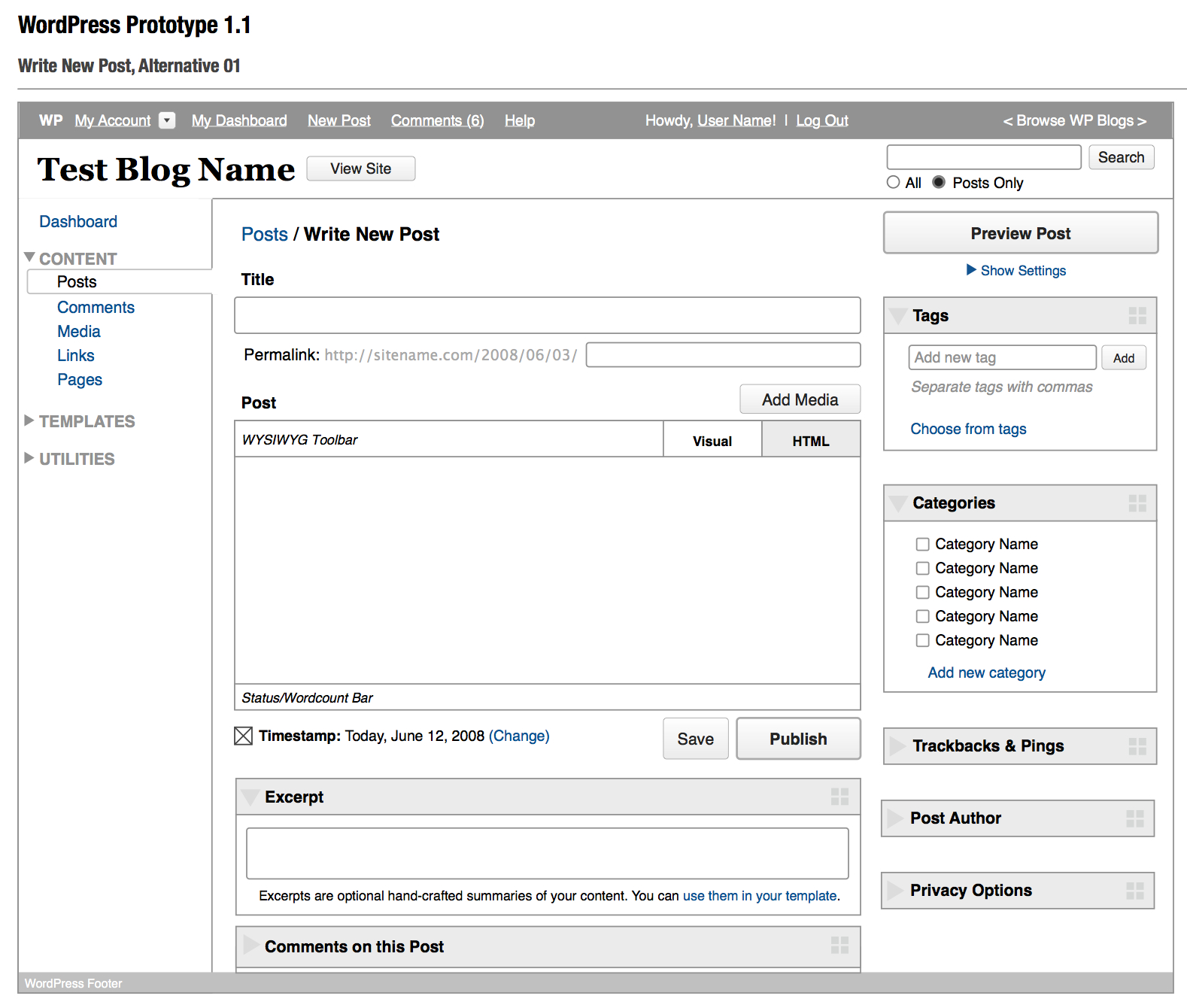

The Write Screen in the Crazyhorse prototype.

The new Write screen had a drag and drop feature -- allowing users to decide which elements got prime screen real estate. They also liked access to post comments; they felt that the new media uploader -- with media library integration -- was a huge improvement.

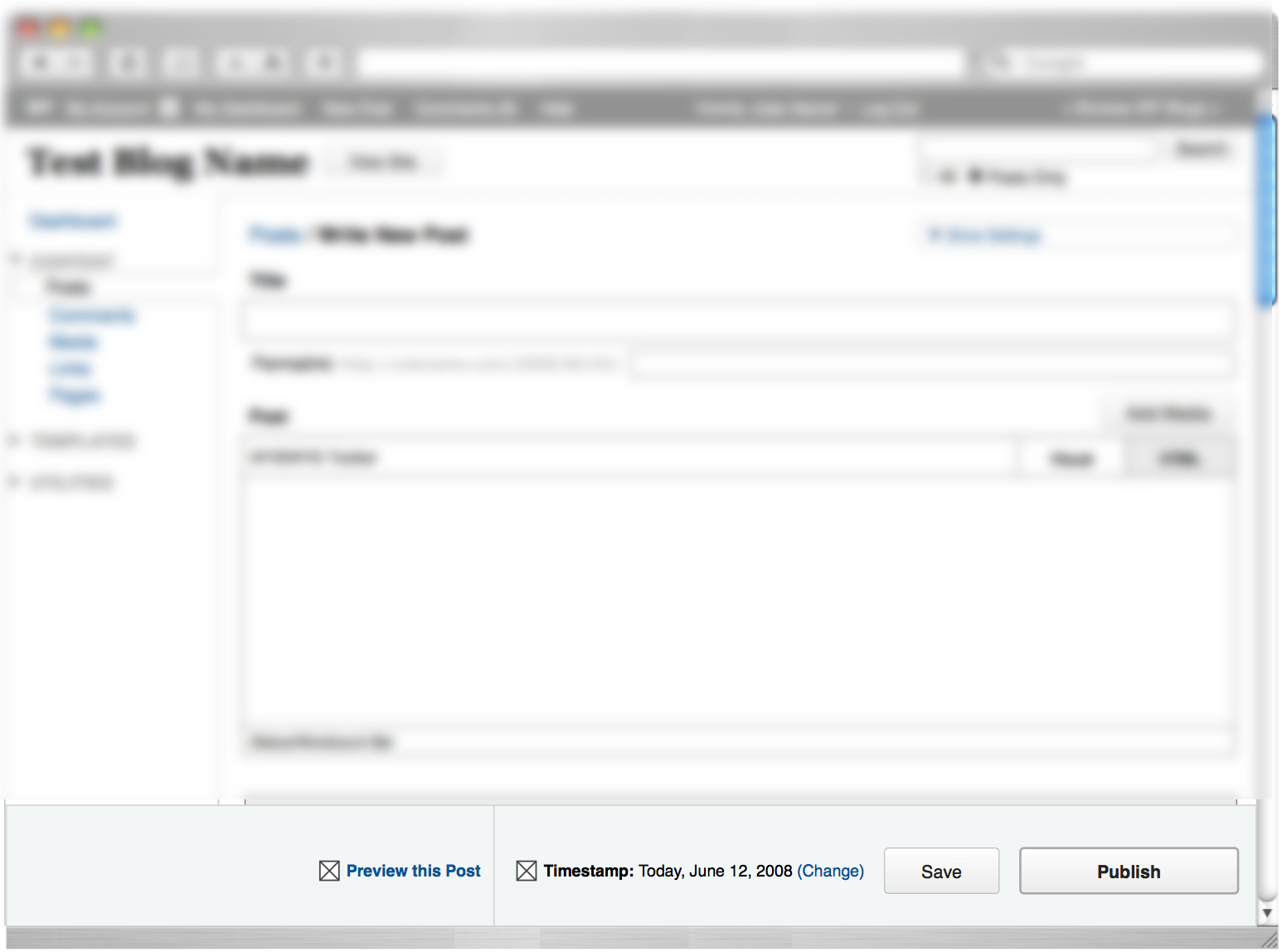

The bottom publish bar in the Crazyhorse prototype.

Users panned a publishing bar that floated at the bottom of the screen -- they'd look at the bar a few times before realizing it contained the Publish button. Some users compared it to a banner ad or thought it part of their browser.

While Happy Cog and project Crazyhorse did user research, they ended up with quite different results. For Happy Cog, Liz interviewed community members and conducted in-person user testing. The Crazyhorse project, however, used eye-tracking technology. This meant that the testers didn't have to rely solely on what participants said; they had insight into what participants were actually looking at during tests. Additionally, gaze trails revealed how users navigated the screen with their eyes, allowing testers to ask: what draws user attention first? Do they miss important UI elements? Do they understand what they're seeing?

With the Crazyhorse prototypes a proven success, fleshing out its design was the next step. When Crazyhorse first merged with trunk, it was a set of live wireframes. Design changes had not been introduced to prevent swaying participants by color or typeface preferences. By the time the Automattic meetup in Breckenridge, Colorado, took place in 2008, Crazyhorse was ready for some color.

At Automattic meetups, small teams work on projects assigned at the beginning of the week. Matt Miklic (MT) (iammattthomas) fn-3 took on Crazyhorse with free design rein. In redesigning the admin, Jen and MT produced many designs. There was a heavy blue variant reminiscent of Shuttle-inspired WordPress, and a version using the light blue, grays, and orange of Happy Cog. Eventually, these two main variants melded into a gray color scheme that WordPress featured until 2013. Andrew Ozz (azaozz) received commit access to help implement the Crazyhorse changes.

Jen's community connection differentiated the Happy Cog and Crazyhorse processes. She kept the community abreast of what was going on. She did testing as an adjunct to the WordPress project to verify actual usability flaws with little community involvement. If it had been just a matter of user color preferences, the Crazyhorse project would have been fruitless. But when testing revealed WordPress' interface needed to change, community dialogue ensued. The designs and the usability report were shared on the development blog. The team surveyed users on navigation options, and the community discussed issues on the wp-hackers mailing list. When WordPress 2.7 released, the launch post lists the posts Jen and the developers wrote about the process. Up to that point, it is the only iteration of the WordPress admin to have such an information trail.

With the Crazyhorse project, WordPress' admin changed drastically -- twice in 2008 alone. When screenshots of the changes appeared on community blogs, the inevitable question was "why are they changing it again?" WordPress 2.5's design hadn't settled in before another huge change came about with the implementation of Crazyhorse in 2.7. A UI change meant that users of varying skill levels needed to relearn how to use WordPress; the growing WordPress tutorial community would need to retake every screenshot and reshoot every video. However, when WordPress users upgraded, the feedback was positive. Users loved the new interface; they found it intuitive and easy to use -- finally demonstrating that it wasn't change they had been unhappy with just nine months earlier -- but the interface itself.

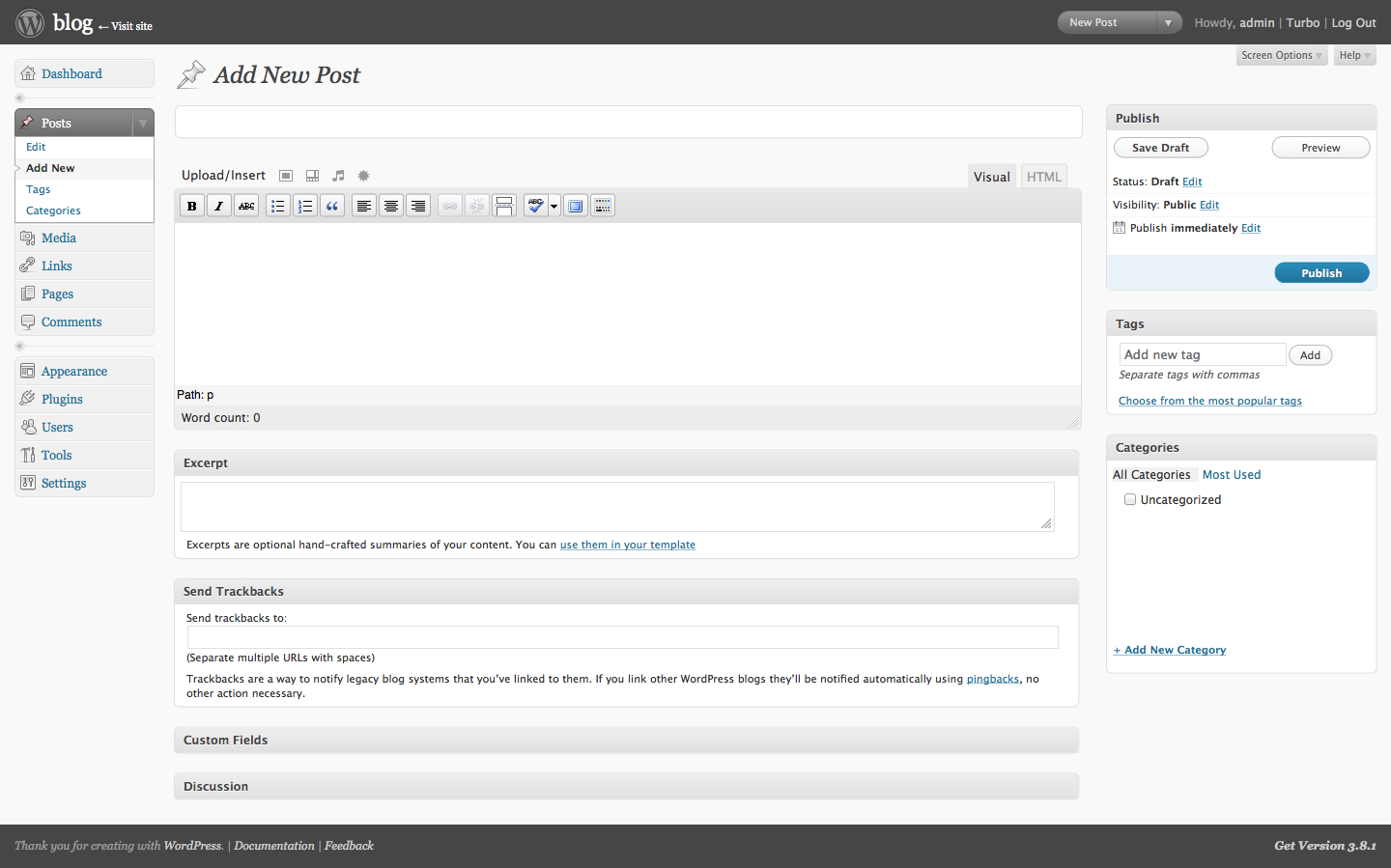

The Write Screen in the WordPress 2.7 admin.

WordPress 2.7 brought the WordPress Plugin Repository to the admin screen. Users no longer had to download a plugin and upload it using FTP. They could search the plugin directory for the features they needed right from their admin, and install the plugin with just a few clicks. This made it much easier for WordPress users to quickly find and install plugins, removing FTP's technical barrier to entry.

WordPress’ documentation also improved. In December 2006, Matt posted to wp-hackers, apologizing for his stance on inline documentation. Inline documentation patches were committed to core. In WordPress 2.7, PHPDocumentor was added, through a big push by Jacob Santos (jacobsantos) and Jennifer Hodgdon (jhodgdon) to get WordPress functions documented in the code. There was also the beginning of an official user handbook.

After completing the Crazyhorse redesign, Jen joined Automattic to work on WordPress. At that time, there was a close core developer group who led the project working in IRC and in Skype. In October 2008, Jen first appeared on wp-hackers. She brought fresh eyes and a completely new perspective. Her background in user testing and user experience was largely absent in the community until she joined the project. “Having someone with actual formal training in testing and user experience, it was just useful,” says Mark Jaquith. “It was not just useful then, but it also changed us. Or at least it changed me. Where I started thinking in these ways as well and becoming better at stepping out of my own head.”

This new focus on user testing and user experience meant that the software would work for everyone who wanted to install it -- not just a small set of users.

31. Themes are GPL too

As the project transformed, so did the wider economy around WordPress. When Brian Gardner released the Revolution theme under the GPL in late 2008, theme developers watched with curiosity to see how it would influence his business, as it seemed counterintuitive to give a product away.

As theme authors watched and waited, commercial theme licensing came to a head. Toward the end of 2008, 200 themes were pulled from the WordPress theme repository. A statement was added to the About page of the Theme Directory that said, "All themes are subject to review. Themes for sites that support 'premium' (non-GPL or compatible) themes will not be approved." This meant that the Theme Directory no longer allowed free GPL themes that linked back to the site of a premium theme seller, whether the themes they sold were GPL or not.

Premium theme developers and the wider community were annoyed. What was the problem with theme authors selling themes? The themes hosted on the Theme Directory were free and complied with the GPL. As so often in the past, people conflated the actions of WordPress.org with Automattic and the company came under fire. Some perceived theme removal as a sign that Automattic didn't want anyone making money.

The theme sellers were genuinely unhappy. Their themes were pulled without warning. Many theme sellers saw their free theme releases as a way of supporting the free software community, and spent considerable time ensuring that they met the theme repository's standards. They felt as though a rug had been pulled from underneath them: they'd done their best to comply with WordPress.org standards, but suddenly it wasn’t enough.

An email from Matt made the rounds in the community:

Thanks for emailing me about the theme directory. The other day I noticed a ton of bad stuff had snuck in like lots of spammy SEO links, themes whose sites said you couldn't modify them (which is a violation of the GPL), etc. Exactly the sort of stuff the theme directory was meant to avoid.There were also a few that violated WP community guidelines, like the domain policy. So since Monday we've been clearing stuff out en mass. If you're kosher with the GPL and don't claim or promote otherwise on your site and your theme was removed, it was probably a mistake. Give us a week to catch up with the bad stuff and then drop a note.

In a podcast on Weblog Tools Collection, Matt discussed his position on the premium theme market (transcription). In the interview, he describes how, while updating a friend’s website, he was looking for WordPress themes in the directory. He found themes with SEO links or linked to SEO sites -- behavior that the Theme Directory had been set up to avoid. The WordPress.org team questioned whether they wanted to allow GPL themes that only served as advertisements for non-GPL themes elsewhere.

In the interview, Matt discussed the distinction between “premium” and “free” themes, and the importance of correct labeling. When it comes to "premium" themes, Matt argued that the word "proprietary" makes more sense than "premium" or even "commercial." GPL themes, such as Brian Gardner's Revolution, could be commercial.

I love what Revolution has done, where they say 'Ok, so we still sold the theme, and we still bundle the support and everything like that with it, but it's also available as GPL.' So they're able to, within the GPL framework, create a business and respect the underlying license of the community that they are building on top of.

Matt made it clear that theme developers were free to do what they wanted on their site, but the WordPress project was equally free to do what it wanted on WordPress.org, and that included whether it should or should not promote businesses that sold non-GPL WordPress products.

Part of the aim of the theme and plugin repositories is to promote theme and plugin developers. The project doesn’t want to promote theme developers who follow the license to get on WordPress.org, but then violate WordPress' license elsewhere. So, theme sellers who sell non-GPL products outside of WordPress.org aren't promoted on the site.

The interview delineated what WordPress.org would and would not support. People got an answer, whether they liked it or not. The storm calmed and cleared the way for 2009, when businesses started to embrace the GPL.

In the months following the debate, people wondered how to sustain a business under the GPL. As the first to embrace the license, Brian Gardner advised other premium theme sellers. In April 2009, Spectacu.la, the theme shop that first posted about themes being removed from the repo, announced that it was going fully GPL. It was followed in June by iThemes and WooThemes.

In July, Matt announced that he had contacted the Software Freedom Law Centre. They provided an opinion on theme licensing:

...the WordPress themes supplied contain elements that are derivative of WordPress's copyrighted code. These themes, being collections of distinct works (images, CSS files, PHP files), need not be GPL-licensed as a whole. Rather, the PHP files are subject to the requirements of the GPL while the images and CSS are not. Third-party developers of such themes may apply restrictive copyrights to these elements if they wish.

WordPress themes are not a separate entity from WordPress itself. As Mark Jaquith wrote later, “As far as the code is concerned, they form one functional unit. The theme code doesn't sit 'on top of' WordPress. It is within it, in multiple different places, with multiple interdependencies. This forms a web of shared data structures and code all contained within a shared memory space.”

Following that announcement, more theme sellers adopted the GPL license, though not all went 100% GPL (i.e., including CSS, images, and JavaScript). Envato, for example, whose marketplace, ThemeForest, was growing in popularity, opted for GPL compliance -- with two licenses, in which the PHP was GPL, but the additional files were proprietary.

Themes that are packaged using this split license follow the GPL. The PHP carries a GPL license and other assets do not. The other elements -- CSS, images, JavaScript, etc. -- usually have some sort of proprietary license. This ensures legal compliance. It aims to protect author rights by removing the freedoms guaranteed by the GPL -- the freedom to use, modify, and distribute modifications. Users are not free to do what they want with a theme licensed in such a way because the CSS and JavaScript are just as important to a theme as the PHP that interacts with WordPress’ internals. But it would be a number of years before this licensing debate would occur.

32. Improving Infrastructure

Jen Mylo emphasized usability, as well as encouraged more people to contribute to WordPress. Conversations happened on wp-hackers and trac, but it wasn’t always obvious how new people could get involved with the project. Project growth compounded the problem; it wasn’t easy for a new contributor to understand what was going on, nor how to contribute. Jen wrote about how to get involved, and the development blog announced patch marathons and bug hunts.

Jen brought more structure to the project: she reinstated weekly development chats with agendas and prevented discussions from disappearing down rabbit holes. When she joined the project, core developers communicated in two main ways: via the IRC chat room and by private Skype channel. Skype's drawback is that it's closed -- it doesn’t create opportunities for other people to get involved. Also, because the main blog at the time, wpdevel.wordpress.com, was on WordPress.com and not WordPress.org, it didn’t feel official. There had been little project management; developers wrote code and pushed it out when it was ready.

At this time, Matt stepped back. Ryan Boren led development, while Jen stepped up to project-manage the software and took a leadership role within the community.

She tried to address communication fragmentation within the project. By 2009, project communication happened in different places: trac, wp-hackers, the #wordpress-dev IRC chat room, wpdevel.wordpress.com, and the WordPress.org development blog. Jen highlights the state of each of WordPress’ primary communication channels: the #wordpress-dev channel had become mostly inactive; wp-hackers had thousands of subscribers, but was often just a troubleshooting forum; the development blog was used for official announcements only; the wpdevel.wordpress.com blog (directed now to http://make.wordpress.org/core) housed team progress updates; Trac had become an unworkable mess with hundreds of irrelevant tickets; and the ideas forum contained many highly voted, but irrelevant threads.

Communication improvements were discussed in a forum thread. Suggestions included: a place other than trac for people to raise things; a way to make it easier for people to write automated unit tests, allowing the community to vote on ideas; greater documentation integration for WordPress and trac; adopting P2 for discussion; and using BuddyPress -- a social-networking plugin that is a sister project to WordPress -- on WordPress.org.

Amid suggestions were complaints: it was noted that no one official read the ideas forum, timezone differences made IRC meetups difficult to attend, and too many communication channels existed -- far too many for people to keep up with. Some people complained about community governance and a lack of transparency. As Jen observed, “Your post just proves the point that communication is an issue. I would not say that WP lacks a clear direction, I would say that it simply hasn't been communicated properly.”

Jen wanted to clarify how project decisions were made. It wasn’t uncommon for people to toss feature requests into IRC chat. People needed to know what each communication channel was for and understand the correct channels to ask questions and request features.

Much of the development discussion had shifted from wp-hackers to trac. Trac's main benefit is that it focuses discussion directly on the bug, feature, or enhancement at hand. That said, as more and more people started using it, it became -- just like wp-hackers -- susceptible to intractable, bikeshed discussions.

Smilies were at the heart of one such recurring discussion. In 2009, a ticket requested replacing WordPress’ smilies with Tango/Gnome smilies. Ryan Boren committed the patch.

The smilies landed first on WordPress.com, which receives daily codebase updates. The feedback was negative and reaction on the trac ticket spiralled; contributors were unhappy that smilies had been changed without discussion. They argued that WordPress had changed users’ content, without giving them any say in it. The discussion spread from trac tickets to community blogs. Some wanted a public poll to aid the decision.

Ryan Boren eventually reverted the change, saying: “Back to the prehistoric smilies that everyone complains about but evidently likes better. :-) I was a fool for not appreciating the explosive topic that is smilies, my bad.” [Fn^1]

As well as trying to fix communication problems, some worked on improving documentation. To commit a patch in WordPress core, there is a review process. The WordPress Codex, on the other hand, is the opposite: any contributor can publish documentation immediately. This is a low-friction way to create documentation, but because it lacked rules and structure, it became difficult to navigate; pages fell out of date, and -- despite the efforts of the documentation team -- it became a mess. User documentation is packaged up with developer documentation, often on the same page, and for many WordPress users and developers, the Codex became less useful. In the meantime, WordPress tutorial blogs proliferated. In the absence of good, official documentation, people went elsewhere.

The Handbook Project sought to create references for theme and plugin development. The team launched a trac instance and wordpress.com blog to manage the handbooks. It can be difficult to recruit long-term help on documentation. With the low-entry barrier, many people make their first WordPress contribution through documentation, but as they figure out the project's contours they move on to contributing to core. The original handbook project was passed between different people, and by 2014 it was near completion.

In mid-2009, WordPress dropped the long-term security branch -- something Mark Jaquith had maintained since 2006. The plan was to maintain it until 2010. During that period, however, there were major changes to WordPress’ security. Backporting those changes into the 2.0.x branch meant complex rewriting that could have introduced new bugs or instability. The developers found that few people were on 2.0; new feature proliferation meant that people upgraded more readily. The legacy branch continued until just six months shy of its 2010 target, and was deprecated in July 2009.

Long-term support branch (LTS) requests remain -- specifically from big companies that use WordPress as a CMS -- though it’s unlikely that WordPress will ever start a new branch. Matt wrote to wp-hackers:

Not backporting is a conscious decision. I would rather invest 100 hours in backward compatibility in a new version than 2 hours in backporting a fix to an obsolete version of WordPress. Plus, as noted by everyone else, backporting was often impossible because it wasn't one or two line fixes, it was architecture changes that would touch dozens of files. The LTS was actually less stable with these "fixes" backported because it had almost no one using it.

Rather than supporting an LTS branch, the project focuses on easy updates and compelling features that entice users to upgrade. This iterative process has continued to improve throughout the project’s history, from Matt’s first mention of upgrades in his 2006 State of the Word address, to automatic updates introduced in WordPress 3.7. This approach focuses development on keeping users secure, rather than trying to maintain older software branches.

[Fn^1] The smiley debate was reignited in 2014, when WordPress.com updated its emoticons and a proposal was made to produce high-dpi smilies for use on retina displays. Once again, people had strong opinions, as seen across community blogs. As of 2015, the smilies are still not updated.

33. Meeting in Person

In December 2009, the core team -- Matt, Mark, Ryan, Westi, Andrew, and Jen -- met in Orlando, Florida. Despite working together on the project for years, it was the first time that some of them were meeting face to face. Working from the Bohemian Hotel lobby, they discussed live project issues, including “the merge, canonical plugins, the WordPress.org site, community stuff, and all the other things that are important but that we never seem to have time to address.” As well as discussing WordPress' vision and goals, they had a trac sprint that edged them closer to shipping WordPress 2.9.

From left to right: Mark Jaquith, Jen Mylo, Andrew Ozz, Peter Westwood, Matt Mullenweg, Ryan Boren.

They posted results to the WordPress news blog, highlighting the breadth of the discussion:

Direction for the coming year(s), canonical plugins, social i18n for plugins, plugin salvage (like UDRP for abandoned plugins), WordPress/MU merge, default themes, CMS functionality (custom taxonomies, types, statuses, queries), cross-content taxonomy, media functions and UI, community “levels” based on activity, defining scope of releases, site menu management, communications within the community, lessons learned from past releases, mentorship programs, trac issues, wordpress.org redesign, documentation, community code of conduct.

Meeting in person allowed them to bounce ideas off of one another and to get work done. Jen recalls:

We sat in these red velvet chairs in the bar of the Bohemian Hotel in Orlando, and when it was time to eat we would go into the dining room and we would eat. And we'd come back and we'd work, and we were on our laptops and actually going through trac as well. And doing bug scrubs, but then we would stop and we would have just conversations and we'd go outside maybe or we'd go out to lunch. And so we kind of mixed it up, and it was just so helpful. Both in terms of just getting to know each other better, and the actual work.

Meetups continue to be part of core development, from small and focused ones with the core team to large gatherings involving the whole community. Members meet at WordCamps, or at dedicated meetups to do code sprints and to discuss the general project and development direction. They provide an opportunity for people to discuss issues without the barrier of a screen, and also to socialize, hang out, and get to know one another better. When community members meet, they generate new ideas and thrash out old ideas in detail. Meetups aren’t, however, without side effects. Meeting in person, by its nature, excludes everyone who isn’t physically present. In a free software project, it's important to balance offline meetups with online activity, which allows everyone to have a say.

The canonical plugins project was discussed at the first core meetup. The WordPress plugin repository was growing, and many plugins did the same thing. Large, complex plugins can transform WordPress, though some plugins had poor code quality, while some were out of date. Sometimes, a developer drops a plugin, leaving users without support or updates -- a big problem if a user relies heavily on the feature. The core development team felt that some plugins warranted a similar process to the core development process, where a group of coders lead a plugin's development, deciding what goes in and what doesn’t, in a similar way to how WordPress, BuddyPress, and bbPress are developed. Rather than having ten SEO plugins, or ten podcasting plugins, for example, there would be one canonical plugin, sanctioned by core with its own official development team.

WordPress’ core development team supported the proposal, which Jen wrote about on the blog; the strong relationship between WordPress core and canonical plugins would ensure plugin code was secure, that they exemplified the highest coding standards, and that they would be tested against new versions of WordPress to ensure compatibility.

Early discussions focused on what to call this cluster of plugins. The community voted and decided on “Core plugins.” Then, a team got to work, which included Westi, Aaron Campbell (aaroncampbell), Austin Matzko (filosofo), Stephen Rider (Strider72), and Pete Mall (PeteMall).

Health Check, which checks a website for common configuration errors and known issues; PodPress, a popular podcasting plugin which had been abandoned; and a proposed plugin to shift the post by email functionality from core into a plugin were the first canonical plugins.

But plugin developers weren’t so enthusiastic. They liked having ownership over their own plugins. The WordPress project was accused of trying to stifle the growing plugin market. Discussions continued among developers about how core plugins might influence them. Justin Tadlock said:

There’s been some great discussion here, but it seems a little one-sided. Most of the people leaving comments are developers. What would make the conversation much better would be to hear from more end users.I will refrain from sharing my opinion until I can gauge what a larger portion of the user base is feeling because, quite frankly, that’s the portion of the community that influences my opinion the most.

User feedback on the thread was positive: any help sifting through the mass of WordPress plugins was a benefit. Why should users have to sift through fifty contact form plugins when there could be one, officially sanctioned plugin that could serve 80% of users? The project didn't intend to kill off the plugin market, and Mark Jaquith tried to calm developer fears: “Core plugins will be safe and stable,” he wrote, “but limited in scope and probably a little bit boring and not completely full-featured."

The core plugins project, however, was beset by other problems. While there was potential for success, they lacked the tools to work effectively across a broad group of plugins. “We didn't have the toolset at the time to do it properly,” says Aaron Campbell, “without stepping outside of the WordPress ecosystem quite a bit and relying on something like a GitHub or something like that, which we prefer not to rely on for things that are really kind of the core of WordPress.”

To properly manage core plugins, the WordPress project’s infrastructure would have to change. When the plugin repository was built, it was designed with one author per plugin; developer collaboration tools didn't exist. (While the plugin repository has become more flexible -- it’s now possible, for example, to have multiple plugin authors -- traditional developer collaboration tools are still lacking.) A system to submit contributions, discuss and modify patches, and merge them are useful for multiple developers working on a single plugin. To develop WordPress, tools have been built around the Subversion repository to make that possible, and the modified trac instance encourages collaboration. But each core plugin would need a replica of the infrastructure that WordPress uses itself, and it became obvious that the plan was untenable.

On top of this, many of the developers were burned out from WordPress 2.9 (and taking a break with the promise of a major release cycle in WordPress 3.0). They didn’t have the time or energy to build core plugins, as well as develop the core product itself. Despite the coverage the project got across the community, and despite the initial burst of energy, the canonical plugins project eventually fizzled out.

34. Update Notifications Pt 2

Community blogs became important gathering spaces for those who wanted to communicate outside the core project's official channels. One of these was WP Candy, a blog started by Michael Cromarty and later taken over by Ryan Imel. Another was WP Tavern, run by Jeff Chandler. WP Candy and WP Tavern became places where the community could share and discuss ideas, as well as vent outside the project's central channels -- and over time, both have hosted many major community debates.

One of the biggest debates was around data collection.

When WordPress 2.3 shipped with update notifications, the initial debate quieted down. Lynne Pope (Elpie) reopened the discussion in 2009 on WP Tavern's forums, and also posted to wp-hackers. Lynne pointed out that Matt had said data collection would be reviewed in WordPress 2.5. She discussed URL collection and asked whether WordPress had a need to collect them, suggesting that an anonymous identifier could replace the blog URL. In the discussion thread on WP Tavern, Lynne went further into her concerns:

wordpress.org is not a legal entity so there is nobody to sue if data is misused. You can't sue a community. There is no disclosure about what data is collected or how it will be used. People are just supposed to trust that volunteers working on an open source project can be relied upon to keep personal data private?

She referenced WordPress.org being cracked in March 2007; if someone were to crack WordPress.org again, they would have access to all the data.

Since much of the data is freely available on the internet, many were unconcerned about the collection, but Lynne pointed out that what isn’t readily available is the totality of that information (WordPress version, PHP version, locale setting, plugin information, and the website’s URL as a package). In 2009, people were growing more concerned about internet privacy. People signed up for social media services that collected huge amounts of data, used to target advertising. A 2009 paper reported that personally identifiable information could be leaked from social networks (PDF) and third parties could link that data with actions on other websites. At the same time, internet users were becoming more vocal about privacy concerns. In February 2009, for example, when Facebook changed its Terms of Service to say that user data would be retained by Facebook even if the user quit the service, the company faced an outcry and was forced to backtrack.

In the midst of these privacy concerns, WordPress was a bastion of the independent web. If a person has privacy concerns, they can avoid using social media; but they can create a website using something like WordPress, on their own server, with complete control over their own data. For some people in the community, data collection tarnishes this independence. There is potential for abuse, and even if there is trust in the people who have access to this data now, there’s no guarantee that others with access to the data will use it in the same way in the future. Mark Jaquith, who had originally opposed the data collection, responded to Lynne on wp-hackers:

The more I thought about it, the more my knee-jerk objections faded away. Your server is doing an HTTP request, so the server knows your server's IP address. You can figure out what blog domains are hosted on that IP with a search on Bing or several other search engines. So if WordPress.org really wanted to know your URL, it could find it. Again, that's just based on the IP address, which you HAVE to send for HTTP to work. If your URL is discoverable, and your IP address has to be sent, withholding the URL doesn't actually get you more privacy, ultimately.

While wp-hackers saw some of this discussion, it mostly took place on WP Tavern. The discussion thread generated 291 responses -- the most popular post in the forum's lifespan. It was also heavily discussed on Weblog Tools Collection under a post from Jeff Chandler, titled “Is WordPress spyware?”

The issue was reopened on WordPress trac, and was proposed for the development chat agenda. Some community members felt that their privacy concerns were valid, and that they weren’t being taken seriously. In the thread, Matt posts that WordPress.org only stores the latest update sent, but no historical data. Historical data is only held in aggregate so that statistics can be provided for plugin and theme developers.

Mark joined the discussion on WP Tavern to share some of the reasons he changed his mind:

- An IP address, which must be sent by the server, is not significantly more anonymous than a URL.

- URLs allow WordPress to verify the identity of a blog. When URLs are hashed it’s no longer possibly to verify the blog identity. Without proper verification, systems that involve plugin rankings based on usage or popularity are open to manipulation and abuse.

- The privacy policy was updated to cover api.wordpress.org.

The core developers stuck with their decisions, not options philosophy; no option was added to turn off update notifications. By the time it was raised again, in 2009, the project could apply another one of its philosophies to making the decision -- the 80% principle: if 80% of users find something useful, then it belongs in core; if not, then it belongs in a plugin. A number of plugins were created to disable update notifications, but only a fraction of people used them. A clear notification of a website or plugin update was more important than adding a preference to satisfy a small number of people within the WordPress community.

WordPress continues to collect data about sites, which is used in a number of ways. The project, for instance, can make informed decisions about which technologies to support. Using the data, it was possible to tell that, in 2010, around 11% of WordPress users were using a PHP version below 5.2, and that fewer than 6% of WordPress users were using MySQL 4.0. Using that information, the development team was confident about dropping support for PHP 4.0 and MySQL 4.0. Browser usage data also helped in the decision to deprecate support for Internet Explorer 6.

Data is helpful when there is a security issue with a plugin, too. The project can detect how many sites have a plugin active and can determine the severity of the issue. In the case of a security issue in a popular plugin, web hosts are informed so that sites with insecure versions of a plugin can be blocked at the host level. Update notifications were also an important stage in the road toward automatic updates for minor releases, which were introduced in WordPress 3.7.

35. The WordPress Foundation

Throughout this time, Automattic held WordPress' trademarks. Trademarks are an important asset to companies, to free software projects, and to anyone who has a product to protect. A trademark represents a project’s reputation, and is a symbol of official endorsement. Free software licenses protect the terms under which a program can be distributed, but they don’t grant trademark rights. In a 2009 article on trademarks in open source projects, Tiki Dare and Harvey Anderson report that of the 65 licenses endorsed by the Open Source Initiative (OSI), 19 don’t mention trademarks, 19 prohibit trademarks in publicity, advertising, and endorsements, and a further 26 explicitly exclude trademark rights.

Trademark law protects a piece of code's marks and branding -- not the code itself. A software project’s code exists in its community's commons, but the trademarks do not. The growing issue of free software trademarks was conceded in 2007 with GPLv3. One clause states that the license may be supplemented with terms “declining to grant rights under trademark law for use of some trade names, trademarks, or service marks.” This reflects that free software communities accept that a trademark is not necessarily linked to the software.

Users and consumers associate a trademark with the original project; the trademark denotes trust, quality, and dependability. It also helps to verify identity: if you’re dealing with a company bearing the Widget Company logo, then you expect to be dealing with Widget Company. This matters in the free software community as much as in the corporate world. A free software project's trademark carries certain assumptions: that the project maintainers and developers are either involved with or officially endorse that product or service, and that it meets quality standards. “Being the source of code arguably matters more than source code in an open-source business,” write Dare and Anderson. “The code is easily replicated, as it is open, but the trust associated with source (or origin) is not replicable. Trademarks are all about source.”

Automattic registered the WordPress trademarks in 2006, but some contributors -- who had helped build the software or started their own local communities -- felt that they had as much right to the trademarks as Automattic. Some community members believed that the community owned the codebase and thus should own the trademarks, not the corporate entity. What Automattic did have, and the community at large didn’t, was the structure and money to protect the trademarks from abuse and dilution. This often came at the cost of good relations with the community.

Automattic had always intended to place the trademarks with the WordPress Foundation, which is a separate entity from the company. Automattic acted as a short-term trademark guardian, protecting the trademarks until another body could take over. This was made clear to the company’s investors at the outset. Phil Black, one of Automattic's first investors, recalls knowing that the trademarks would not remain with the company. “It wasn’t like Matt was proposing something to us where we felt like a significant asset was being lost,” says Phil. “A significant asset was being transferred to the right third party as we thought that it should have been.”

The Foundation counterbalances Automattic, providing checks and balances should Automattic ever be acquired. “Let’s say Evil Co. ran Automattic,” says Matt, “and Evil Co. only cares about making money. The balance between WordPress.org and the WordPress Foundation and WordPress.com is such that I think even Evil Co. would do the right thing with regard to the community and the code and everything.”

The Foundation took longer to set up than expected; various factors needed to be in place before it launched. Before the trademarks could be transferred, they needed to be properly secured and protected. Toni Schneider managed this during his early days at Automattic. It also took a long time to register the non-profit with the IRS. Because non-profits are tax-exempt, it can be difficult to set one up. Matt wanted the Foundation to hold the trademarks, but simply holding trademarks is not considered a legitimate non-profit activity. Applications sent to the IRS were denied for several years. In the end, the WordPress Foundation received 501(c)(3) status as an organization charged with educating people about WordPress and related free software projects.

The WordPress Foundation’s website states its mission:

The point of the foundation is to ensure free access, in perpetuity, to the software projects we support. People and businesses may come and go, so it is important to ensure that the source code for these projects will survive beyond the current contributor base, that we may create a stable platform for web publishing for generations to come. As part of this mission, the Foundation will be responsible for protecting the WordPress, WordCamp, and related trademarks. A 501(c)3 non-profit organization, the WordPress Foundation will also pursue a charter to educate the public about WordPress and related open source software.

The WordPress Foundation was launched in January 2010. Automattic transferred the trademarks later that year in September. As part of the transfer, Automattic was granted use of WordPress for WordPress.com, but not for any future domains. Matt was granted a license for WordPress.org and WordPress.net. As well as transferring the trademarks for WordPress itself, the company also transferred the WordCamp name. As with WordPress itself, this protects WordCamps as non-profit, educational events in perpetuity.

The community was pleased with decoupling WordPress the project from Automattic the company. It gave people more confidence that Automattic was not out to dominate the WordPress commercial ecosystem. Despite some initial confusion about how people were allowed to use the WordPress trademark, eventually it settled down.

In the same year, both Matt and Automattic explored different ways to support the WordPress project. Matt set up another company, Audrey Capital, which is the home for his investments. Audrey Capital allows him to hire developers for tasks that he doesn’t have time for, and this separation offers some balance between people who contribute to WordPress and who aren’t employed at Automattic.

“The idea was to kind of have five people at Automattic working on WordPress core, five people at Audrey working on WordPress core, and then I’ll try to get the different web hosts to each hire a person or two each, and so there’ll be between the three, fifteen-ish people, full-time on WordPress.org,” says Matt.

Developer Samuel Wood (Otto42) was Audrey Capital’s first employee. Matt and Otto share a love for barbecue. Otto was looking for someone to sponsor a BBQ team at the international barbecue festival in Memphis, Tennessee. Knowing Matt liked barbecue, Otto asked him to sponsor the team. Matt said yes and went to Memphis for the festival. The following year, Matt sponsored the group again, and eventually asked Otto to work for him at Audrey. Andrew Nacin -- who would go on to become a lead developer of WordPress -- joined Otto, and since then, Audrey has hired three more people to work on the WordPress project.

At the same time, changes at Automattic would have an ongoing influence on the project. By August 2010, the company had more than sixty employees. The sheer number of people meant that the completely flat structure was becoming harder to manage. The company moved to a team structure in which groups of people worked on different projects: themes, VaultPress, and support, for example. One of the newest teams at Automattic was the Dot Org Team, dedicated to working on the free software project. Ongoing members were Ryan Boren and Andrew Ozz, WordPress lead developers; Jen Mylo, formerly WordPress' UX lead responsible for the Crazyhorse redesign; and Andrea Middleton, who managed WordCamps.

Teams are fairly fluid inside Automattic, and people come to the Dot Org Team to work on the WordPress project, often bringing with them the knowledge and skills that they've developed elsewhere in the company. Employees can also do a "Dot Org rotation," which means that they work on the WordPress project for a release cycle.

The Dot Org Team has helped mitigate the effects of hiring from the community. Seven out of the first ten Automattic employees came from the WordPress community, and over the years, the company has hired a number of contributors. While this has been good for individuals and for Automattic, it hasn't always had a positive effect. When WordPress.com was almost the sole focus, contributors worked on the core project, which benefitted both the project and Automattic. Some early contributors who became Automattic employees found themselves spending less and less time on the project. Mark Riley, who was employed to do support, found that he had no time to help out in the WordPress.org support forums. For other people, this has happened slowly, over time, as Automattic has expanded into other products, while the core project evolved in a different direction -- one with governance and structures, wildly different from the days of throwing up patches, heated discussions on wp-hackers, and waiting for Matt or Ryan to commit code.

The Dot Org Team has formed a bridge between the company and the community, ensuring that there are people within Automattic whose attention is 100% on growing the WordPress product and project. In 2014, the number of people working on WordPress from Automattic expanded even further. The Dot Org Team split into two: a developer team that works on the core software and on WordPress.org (Team Apollo), and a community team that is focused on events and the community (Team Tardis).

36. WordPress 3.0

WordPress 3.0 arrived in 2010, bringing change not only to the software, but to the development process and project structure. Commit access was opened up and all these changes shaped how the project works today. WordPress’ philosophy -- deadlines are not arbitrary -- was seriously challenged.

In January 2010, Dion Hulse (dd32) received commit access during the 3.0 release cycle. In the post announcing Dion’s access, Matt outlines a new goal for the project:

One of the goals for the team in 2010 is to greatly expand the number of people with direct commit access, so the emphasis is more on review and collaboration. Right now commit access is tied up with being a “lead developer,” of which we’ve always found a small group of 3-5 works best, but now we want commit to be more a recognition of trust, quality, and most importantly activity, and something that can dynamically flow in and out as their level of commitment (har har) changes and decoupled from the “lead dev” role.

This new approach and decoupling commit access from the lead developer role signaled a big change when every patch went through either Matt or Ryan. There was a need to extend trust to contributors, without necessarily giving them leadership roles within the project. While there were no formal rules, several contributors received commit access: Ron Rennick (wpmuguru), focused on multisite, Dion focused on HTTP, and Daryl Koopersmith (koop) worked on front-end development, while Andrew Nacin (nacin) was the codebase generalist.

As well as a symbol of trust, extended commit access meant that tickets and bottlenecks were cleared quickly. When lead developers got distracted by life and work, Ryan Boren carried the load. New committers reviewed and committed tickets.

April 13, 2010 was WordPress 3.0's release date. Similar to prior releases -- despite having a deadline -- development focused on scope and headline features, rather than meeting the date. Three main features were defined in the scope chat: merging WordPress MU with WordPress, menus, and a new default theme to replace Kubrick.

Merging WordPress MU with WordPress came for several reasons: WordPress MU was difficult to maintain, 95% of the code was the same as the main WordPress codebase, and Donncha had to manually merge new features post-release. Because WordPress MU hadn't gained attention from plugin developers, it felt separate from the main WordPress project. To give users a clean upgrade path, WordPress MU merged with WordPress.

Ron Rennick, a longtime MU user, assisted with the merge. He and Andrea, his wife, had used WordPress MU for years for their homeschooling blogging network. His script turned a WordPress install into a WordPress MU install. He reverse engineered his script to bring MU functionality into WordPress, ensuring a way to convert a single WordPress install to a Multisite install.

Ron ran a diff fn-4 against the WordPress MU code, looked for differences in the codebase, and merged them into WordPress core. Ryan Boren and Andrew Nacin cleaned up the code. Ron also merged features absent from WordPress MU in plugins, such as domain mapping -- a feature originally developed by Donncha.

Plan A was to allow users to upgrade to WordPress Multisite with one click. “The reason we decided not to do that,” says Ron, “is that a lot of the shared hosts would not have been happy if their users could just take any WordPress install, click a button -- without actually knowing anything about what was going to happen -- and convert it over to Multisite. The decision was made to actually make it a physical process that they had to go through.” To change a WordPress installation into Multisite, WordPress users have to edit wp-config. They need basic technical knowledge.

Terminology was one of the biggest headaches surrounding the merge. In WordPress 3.0, the project decided to move away from the word “blog,” and instead refer to a WordPress installation as a “site.” More and more people were using WordPress as a CMS, so the “site” label felt more appropriate. However, in WordPress MU, the parent -- example.org -- is a site, while the subdomain blog.example.org is a blog. With WordPress MU and WordPress merging, which one was the site? An individual WordPress install, or a WordPress install that hosted many blogs? WordPress MU became WordPress Multisite, but that wasn’t the end of it.

To complicate matters further, WordPress MU had a function getsiteoption, which gets options for the entire network, and getblogoption which gets options for individual sites. The functions, therefore, don’t relate entirely to the user interface. That was just one of the functions that caused problems, as Andrew Nacin noted.

Custom post types and custom taxonomies were two big changes in WordPress 3.0. The default content types in WordPress are posts, pages, attachments, revisions, and nav menus (from WordPress 3.0), and the default taxonomies are categories and tags. In WordPress 3.0, custom post types and taxonomies were given a user interface. So instead of being restricted to just posts and pages, developers could create themes and plugins that had completely new types of content for users, such as testimonials for a business site or books for a book review website. This opened up totally new avenues for theme and plugin developers, and those building custom sites for clients.

Menus were the big user-facing feature for WordPress 3.0. At the time, it wasn’t easy for people to add navigation menus to their websites. Menu plugins were popular, so much so that it was obvious that the feature met the 80/20 rule. (Would 80% of WordPress users take advantage of the feature? If yes, put it in core, if not, keep it in a plugin.) The menus ticket was opened in January 2010. The first approach was to create a menus interface similar to the widgets interface. By mid-February, however, little progress had been made. Proposals competed on how menus should work. Ryan and Jen contacted WooThemes to discuss bringing their custom woo navigation into WordPress core. This was just days before the planned feature freeze on February 15, 2010.

WooThemes’ custom navigation made it easy for users to add menus to their websites. Developer Jeffrey Pearce (Jeffikus) worked with Ptah Dunbar (ptahdunbar) on the core team to modify WooThemes' code for core, and to prepare core for the feature. At the time, core updated jQuery to match the version WooThemes' theme framework used. The original WooThemes codebase created new database tables for the menus. As a general rule, WordPress avoids adding tables to the MySQL database. Instead, core developers used custom post types -- existing core functionality.

However, Jeffrey found the time difference challenging. Jeffrey is based in South Africa; core development work happens mostly on US time zones. Development chats took place at 20:30 UTC, which was 22:30 in South Africa. Additionally, Ptah and Jeffrey kept missing each other on Skype.

An environment in which everyone had a voice and an opinion wasn’t something that WooThemes was used to in their development process. Adii Pienaar, co-founder of WooThemes, described the process as excruciating. One of the main points of contention was that WooThemes had originally put the menus in the center of the screen with boxes to add menu items on the right-hand side. WooThemes had invested time into designing it that way, but the menu interface was flipped around to match WordPress’ left to right interface convention.

The menu integration was one of the first times that the project had worked directly with a commercial business (other than Automattic). While the process was not always completely smooth, both sides benefitted from collaborating. WordPress got its menu system. While not exactly the same as the menu system that WooThemes created, it accelerated development. WooThemes got the satisfaction of seeing its code used by every WordPress user. Not everyone felt that WooThemes received adequate credit, though Jeff didn't share this viewpoint. “Just to have our name on the contributors' wall -- that to me was good enough,” he says. “It’s nice just to be able to say, I built a part of WordPress. No one can ever take that away from me. That was recognition enough for me.”

WordPress 3.0 ended up being a huge release, and while menu discussion continued, launch was delayed again and again. By April, the core team was still sending around wireframes -- discussing whether menus should be pulled from 3.0. The release candidate kept being pushed back. Matt reiterated one of WordPress’ key philosophies:

Deadlines are not arbitrary, they’re a promise we make to ourselves and our users that helps us rein in the endless possibilities of things that could be a part of every release.

Feature-led releases meant delays. Menus caused the hold-up with WordPress 3.0, with prevarication over the user interface and implementation. The final release was packed full of features that included the new menus, the WordPress Multisite merge, custom post type and taxonomy UI, custom backgrounds and headers, and an admin color scheme refresh. Any of these features could have been pushed to the next release, but there was no willingness to do so.

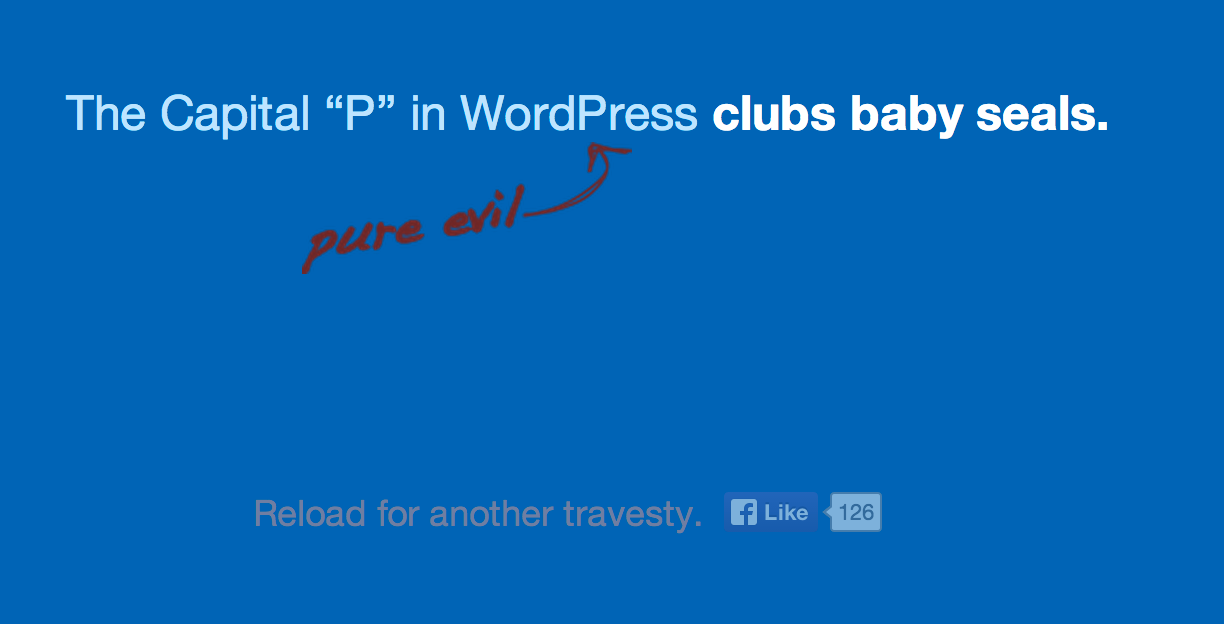

One of the more controversial changes in WordPress 3.0 was a new function called capitalPdangit. This function ensures that the letter "p" in WordPress is capitalized. People felt that WordPress was messing with their content -- that this automatic correction was the start of a slippery slope. For some, it was overbearing pedantry, for others, censorship. WordPress has no business changing what people wrote. Some saw it as incommensurate with the project's core freedoms: openness, freedom, and community.

Most importantly, the filter broke URLs in some instances. This was reported before WordPress 3.0’s release, but because the filter had already worked well on WordPress.com, it wasn’t fixed immediately. For example, a user reported that his image, named “WordpressLogoblue-m.png” was broken because it had been renamed to “WordPressLogoblue-m.png.” Upon upgrading to WordPress 3.0, other users -- those with folders with the lowercase "p" -- had the same problem. As well as folders, URLs with the lowercase "p" were broken. Hosts saw an uptick in support requests. "When 3.0 arrived,” says Mike Schroder (dh-shredder) of Dreamhost, “we had a deluge of support with broken URLs due to capitalPdangit() applying to all content. This was a particular problem because it was popular among customers to use /wordpress as a subdirectory for their install. We helped customers with temporary workarounds in the meantime, but were very happy to see the issue fixed in 3.0.1." Mark Jaquith added a fix, but many contributors believed WordPress should never have broken users’ websites in the first place.

The capitalPdangit function isn’t the only WordPress function that filters content. Other filters include emoticons, autop, shortcodes, texturize, special characters, curly quotes, tag balancing, filtered HTML / kses, and comment link nofollows. From the core developers' perspective, capitalizing the "p" in WordPress didn’t actually change the meaning of the sentence, except in edge cases such as, “Wordpress is the incorrect capitalization of WordPress.”

Core developers became frustrated by the hyperbole around the filter and the time spent arguing about it. In a comment on Justin Tadlock’s blog, Mark Jaquith said:

Calling corrections censorship is absurd. It is no less absurd when the capitalization of a single letter is called censorship. There is actual censorship going on all around the world at this very moment. I’m damn proud of the fact that WordPress is being used to publish content that makes governments around the world afraid of the citizens who publish it. I’m incredulous that people are making a fuss about a single character (which is only one of dozens of automatic corrections that WordPress makes). It’s free software that is easily extended (or crippled) by plugins. If the thought of going the rest of your life without misspelling WordPress it too much to bear, you have an easy out. Take it, take a deep breath, and try to pick your battles.”

A website Mark created reflects the position of many of the core developers on the capitalPdangit discussion:

While this had all of the hallmarks of a bikeshed, there were some procedural issues that community members felt ought to be taken seriously. Whether the WordPress software capitalized the "p" in WordPress or not, the method by which the function was added to core broke accepted procedure: no ticket was opened, no patch uploaded to trac. The code was simply committed. For some, this set up an “us vs. them” mentality, where some core developers could commit code as they saw fit, while everyone else in the community was subject to a different process.

Despite these development snafus, with WordPress 3.0, the platform matured, making “WordPress as a CMS” a reality. It also introduced a new default theme for WordPress, ushering in a new approach with new annual default themes. Gone was Kubrick, with its bold, blue header. The new theme, Twenty Ten, showcased WordPress’ new menus feature.

WordPress 3.0 ushered in changes to the project and the development process. It opened up WordPress to a new generation of people who became increasingly active. Over the coming releases, some of those committers would take on leadership, both in terms of development and in the wider community.

37. The WordCamp Guidelines

By the time WordPress 3.0 came out in 2010, 107 WordCamps had been held across the world, in countries as diverse as Thailand, Germany, the Philippines, Canada, Israel, and Chile. WordCamps create spaces in which WordPress users, developers, and designers converge to listen to presentations and talk about WordPress. Participants meet project leaders, socialize, and get to know one another. WordCamps attract new contributors, and developers meet with users to learn about problems they experience with WordPress.

WordCamps have always been informal, and through the early events, the organization was just as informal as the events themselves. In the beginning, interested community members simply decided to organize a WordCamp. They contacted Automattic for stickers, buttons, and other swag. A blog for WordCamp organizers was set up in 2009, so that organizers could communicate with one another.

In May 2010, Jen took over as central WordCamp liaison, instituting changes in WordCamp organization. Jen said that “WordCamps are meant to promote the philosophies behind WordPress itself.” Without any real structure and oversight, things happened contrary to WordPress' core philosophies. For example, WordCamps accepted sponsorship from people and companies in violation of WordPress’ license -- the GPL. While non-GPL compliant developers and companies are welcome to attend WordCamps, they’re not able to organize, sponsor, speak, or volunteer. This is because WordCamps are official platforms of the WordPress project, and the project doesn’t want to endorse or publicize products contrary to its own ethos.

Without central oversight, issues arose at WordCamps. Many WordCamps ran without budgets. Some organizers took money for themselves. One WordCamp accepted sponsorship money, the WordCamp folded, and the sponsorship never returned. Another opened for registration just so that the organizer could compile a mailing list to which they could send marketing emails.

WordCamps needed better oversight, including clear guidelines. From May 2010 onward, that started to happen. Jen published the first set of WordCamp guidelines.

WordCamps should be:

- about WordPress.

- open to all, easy to access, and shared with the community.

- locally organized and focused.

- open to lots of volunteers.

- stand-alone events.

- promote WordPress’ philosophy.

- not be about making money.

In some quarters, the changes went down badly. Others were more relaxed about the changes, but they, too, asked why people who promoted non-GPL products would be banned from speaking. While many WordPress theme shops were 100% GPL, those that weren't 100% GPL were indignant that they would have to be GPL-compliant just to speak at a WordCamp.

There were frustrations about the way in which the guidelines emerged. They were published without consultation with WordCamp organizers and appeared to be an edict from above. Brad Williams (williamsba1) says: “I think it probably would have been more beneficial across the board for some more open conversations between the Foundation and the organizers to make sure, one, that these guidelines make sense and that we're all on the same page and if there was any concerns get those out in the open." As with previous decisions, the guidelines weren’t part of a conversation between the Foundation and the WordCamp community. When they appeared, they seemed unilateral and the rationale was poorly communicated.

Some guidelines responded to community problems. It is important that WordCamps focus on the software. At least 80% of the content should be about WordPress. Presentations about social media, SEO, and broader technology issues should not be the event's main focus. Other guidelines were more about ensuring that events about WordPress mirror the project's organization and ethos. Like the project, WordCamps ought to be volunteer-driven, from the organizers, to the speakers, to the volunteers who help out during the day. The WordPress project was built by volunteers and WordPress events run on volunteer power. WordCamps should also be accessible to anyone who chooses to attend. This means keeping ticket prices intentionally low.

The guidelines have evolved over the years, with community feedback. While not everyone is happy with them, WordCamps continue to flourish around the world.

38. Dealing with a Growing Project

By the time WordPress 3.0 launched, more people were interested in WordPress than ever before. In the early days the project attracted developers, bloggers, and people interested in helping others via support or writing documentation. But several factors meant that people with diverse backgrounds were getting involved.

WordPress 2.7 demonstrated that making software isn't just about writing code; design, user experience, UI expertise, and testing are all very much part of the process. Useful software requires a diverse set of eyes. This means attracting new contributors by illuminating the different ways one can contribute to the project.

While development, documentation, and support are obvious ways to participate, in 2009, Jen Mylo wrote about the different ways for people to contribute to the project. One was graphic design. After a 2008 icon contest was successful, the project tried to find more ways for designers to contribute. A new trac component for graphic design tasks ensued, and designers were invited to iterate WordPress' visual design. People were also encouraged to participate with usability testing. WordPress 2.7's success stemmed from user testing during the development cycle. The development team was keen to replicate this process in future releases. Jen also invited people to contribute by sharing ideas, feedback, and opinions.

As well as her work on the development blog, Jen and other project leaders spoke at WordCamps to encourage community involvement. Developing a strong community was becoming as important as software development.

Project infrastructure changes also affected WordPress’ growth, particularly in the third-party developer community. Users could readily find themes and plugins. Plugins iterated more quickly; the plugin directory launched in March 2007 in WordPress 2.3. Later that year, the plugin update notification system arrived, and from WordPress 2.7 onward, users could install plugins from their admin screens. Theme improvements were similar, if a little later. The theme directory launched in July 2008; it arrived on admin screens with WordPress 2.8 in 2009. Giving users more access to plugins and themes meant third-party developers had much greater access to users than ever. The theme and plugin directory were growing exponentially.

The theme directory was becoming more difficult to manage with the exponential theme growth. Joseph Scott (josephscott) developed the first version of the theme directory, and spent much of his time reviewing themes and providing feedback. While many theme issues were security-related, Joseph also advocated for best practices. Soon the work became too much for one person.

Joseph wrote:

The theme directory has been chugging along for more than a year now. During that time we’ve tinkered with the review process and some of the management tools, but haven’t really opened it up as much as we’d like. It’s time to rip off the band-aid and take some action; to that end, we’re looking for community members to help with the process of reviewing themes for the directory.

No one knew how the experiment would turn out. A rush of people signed up for the new mailing list; guidelines were drawn up. Though the overall response was positive, some felt that the guidelines were too restrictive -- that some theme requirements should be recommendations. On the WP Tavern forums, Justin Tadlock outlined some concerns, specifically that guidelines didn’t allow themes with custom template hierarchies or custom image systems. Some believed the theme review team should check for spam and other objectionable practices. Other developers simply decided to remove their themes from the directory.

Manpower was a problem for those reviewing themes. The review queue was clogged with 100 themes by July 2010; new themes were added every day. Only three or four people were actively reviewing themes. Over time, automated processes and new tools have improved the theme review process. For example, the theme check plugin tests the theme against all of the latest theme review standards.

But despite the teething problems, the theme reviewers have a system that benefits both users and developers: users get safe themes approved by WordPress.org, and theme developers get feedback and help on their themes. There have been other, long-term benefits. Joseph says:

...looking back on it over the long term it's been nice to see some folks who started way back then and have gone on to be very successful as far as developing their own themes, commercial themes, while still supporting free and open source at the same time. I think over the long term it's been rewarding to see that jumping off point for people to be able to continue to produce more themes, and very well regarded and high quality themes.

As the WordPress project settled into concrete groups, communication needed to improve. Core product development was discussed on wpdevel.wordpress.com. Other teams were scattered over mailing lists and wordpress.com blogs. Toward the end of 2010, a new blog network was set up on WordPress.org -- make.WordPress.org became the new home for WordPress contributor teams, with blogs for core, UI, theme review, and accessibility. Over time new blogs such as support, documentation, plugins, and community, were added.

Each make.WordPress.org blog runs the P2 theme. Created by Automattic for internal communication, P2 is a microblogging tool that allows users to post on the front end -- similar to Twitter -- without the 140-character limit. Threaded comments on posts allow for discussion. Unless made completely open, only people who are editors of a blog can write a post while anyone is able to comment.

The "make" blogs are an important centralized space on WordPress.org where contributors gather. If a contributor is interested in core development, they can follow the core blog; forum moderators can follow the support blog; people with a UI focus can follow the UI blog. Contributors can subscribe to the blogs and follow along with what’s going on from their email inboxes.

By moving everything onto P2-themed blogs on make.WordPress.org, the conversation's tone has changed -- everything takes place in public. This encourages a more respectful attitude among community members. The focus is on getting work done, rather than devolving into arguments.

These sorts of focused communication improvements have helped the project to build capacity and grow. What often happens is that a need appears, a call goes out, and if enough people answer the call, the project moves forward. This sort of community and capacity building is an important part of running a successful free software project. As the community grows, needs change and new contribution areas open up. A project that grows so far beyond its hacker roots that it encompasses a diverse set of contributors is a healthy one.

39. Thesis

By mid-2010, one theme was still a GPL holdout: Thesis, from DIYThemes. Created by theme designer Chris Pearson and blogger Brian Clark, Thesis was popular as a feature-heavy framework -- it gave users many more options than most WordPress themes. Users can customize every element of their website via the user interface. On the original about page, Chris states Thesis' aim: "I wanted a framework that had it all -- killer typography, a dynamically resizable layout, intelligent code, airtight optimization, and tons of flexibility." Tech blogs featured Thesis and high profile bloggers, including Matt Cutts, Chris Brogan, and Darren Rowse adopted it.

Chris Pearson was well-respected in the community; he'd already developed Cutline and PressRow before moving into the premium theme market with Thesis. A mid-2009 ThemeShaper post recalls Thesis' influence as "The Pearson Principle": "Bloggers want powerfully simple design on an equally robust framework." With themes such as Revolution and Premium News, theme developers were already creating feature-rich themes, and Thesis cemented that approach, ushering in the era of the theme framework fn-5. Chris called this approach "ubiquitous design." A theme wasn't simply a website skin, it was a tool to build your website. It took another four years before theme developers stopped packing themes with options and started moving features into plugins.

While theme vendors adopted the GPL, Thesis held out. Discussions between DIYThemes and Automattic went nowhere and relationships fractured. In June 2009, Brian and Toni were in discussions when a blogger's comment thread was hijacked. A long debate about Thesis and the GPL ensued. Matt urged people to move away from Thesis, saying "if you care about the philosophical underpinnings of WordPress please consider putting your support behind something that isn't hostile to WordPress' core freedoms and GPL license."

In July 2010, the WordPress/Thesis debate reignited after Chris Pearson's interview on Mixergy. In it, Chris shares Thesis' revenue figures, putting a conservative estimate at 1.2 million dollars within 16 to 18 months.

Just over a week later, Matt and Chris took to Twitter. Matt was unhappy about Chris flaunting revenue and the GPL -- violating WordPress' license. Cutting remarks ensued until Andrew Warner from Mixergy set up an impromptu, live debate to discuss the issues. The hour-long discussion aired both sides of the argument. Matt argued that Thesis was built on GPL software -- WordPress -- and must honor the license. Matt suggested that Chris was disrespectful of all WordPress authors and that he was breaking the law. Chris said adopting the GPL meant giving up his rights and losing piracy protection. He argued that "what I've done stands alone outside of WordPress completely," and that Thesis "does not inherit anything from WordPress." The argument descended into a rambling discussion of economics, and the conversation ended when Matt threatened to sue Chris if he refusesed to comply with the GPL.

Matt, Automattic, and WordPress took public action against Thesis following the interview. Matt offered to buy Thesis users an alternative premium theme, consultants using Thesis were removed from the Code Poet directory of WordPress consultants, and Chris Pearson's other themes -- Cutline and PressRow -- were removed from WordPress.com.

Matt wasn't the only one in the WordPress community to come out swinging against Thesis. Other lead and core developers wrote about their GPL / Thesis stance. Ryan Boren wrote, "where do I stand as one of the primary copyright holders of WordPress? I'd like to see the PHP parts of themes retain the GPL. Aside from preserving the spirit of WordPress, respecting the open source ecosystem in which it thrives, and avoiding questionable legal ground, retaining the GPL is practical." Mark Jaquith noted that WordPress themes don't sit on top of, they're interdependent on WordPress:

...in multiple different places, with multiple interdependencies. This forms a web of shared data structures and code all contained within a shared memory space. If you followed the code execution for Thesis as it jumped between WordPress core code and Thesis-specific code, you'd get a headache, because you'd be jumping back and forth literally hundreds of times.

Even developers who believed themes aren't derivative of WordPress declared Thesis derivative. Developer Drew Blas wrote a script comparing every line of WordPress and Thesis. His script revealed several instances of Thesis code taken from WordPress. Core developer Andrew Nacin pointed out that Thesis' own inline documentation declared: "This function is mostly copy pasta from WP (wp-includes/media.php), but with minor alteration to play more nicely with our styling."

A former employee of DIYThemes left a comment on Matt's blog: