The Story of WordPress - Part 6

You are reading the sixth part of the series, find the whole series at series/wpbook.

40. The Transition to Release Leads

From late 2011 on, the development process iterated. Not optimal, it lacked accountability. Bottlenecks festered and deadlines passed. Each release from WordPress 3.4 on endured major development process change; it wasn’t until WordPress 3.8 that process experimentation slowed.

Experimentation started at the core team meetup in Tybee Island, Georgia, in December 2011. Lead developers, committers, and active core developers discussed the project’s issues and roadmap, informing the scope setting meeting for WordPress 3.4 on January 4, 2012.

The scope chat notes cover the issues discussed. The team acknowledged process problems. Jen listed the issues: “lack of good time estimation, resource bottlenecks, lack of accountability, unknown/variable time commitments/disappearing devs, overassignment of tasks to some people, reluctance to cut features to meet deadline.”

They split feature development into teams; two contributors would lead each team to reduce contributor overextension and project abandonment.

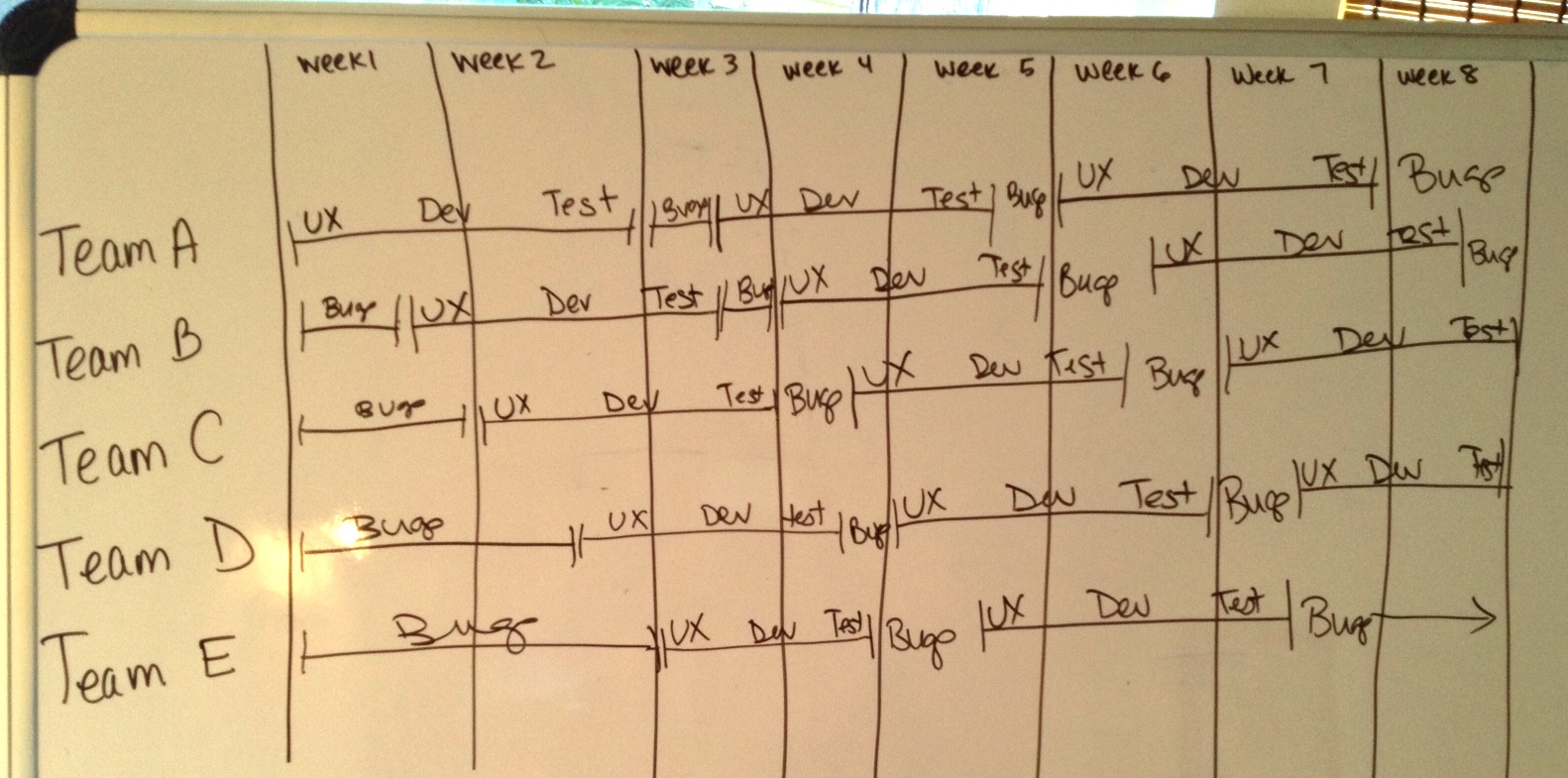

Ideally, a lead developer or a committer would lead each feature team. To help engage and mentor new contributors, one new contributor would pair with each lead or committer. Each team had to post regular updates and deliver their feature on time. They created a schedule with overlapping cycles that encompassed development, UX, and bug fixes to reduce bottlenecks.

The proposal for the 3.4 release process.

The team decided that releases would have a specific focus. WordPress 3.3 had been a cluster of disparate features, some of which had been pulled because they weren't ready. WordPress 3.4 was the first cycle to have an overarching focus -- appearance/switching themes. The development team worked on improving both front-end and admin features that adjust a site’s appearance.

Between WordPress 3.4 and 3.5, the project leadership approach evolved -- a change that had started back in WordPress 3.0 when Dion Hulse became a committer. Though Dion received commit access, he was not a lead developer. This was the first step toward decoupling the lead developer position from commit access. To reduce bottlenecks, the project needed committers, but not necessarily more lead developers. Separating the roles offered opportunities for strong coders and patch triagers, and for those who wanted to contribute, but not necessarily in a leadership role.

And yet, confusion reigned on what the lead developer title actually entailed. Core team members perceived the role differently; no one agreed on what the lead developer title meant. For Mark Jaquith, the lead developer role has changed organically over the years. To begin with, the role related to coding. Over time, it transitioned, particularly around the growth of WordCamps: "We started going around and talking to users about some of the philosophy behind WordPress and the direction we wanted to take. It became more of a general leadership role in practice." The role also evolved as lead developers worked with the community: often, lead developers responded to comment threads to address issues, or speak up on behalf of the project. However, the role had never been formally clarified. While the lead developers handled many coding decisions, their additional responsibilities and authority were unclear. Did they have authority across the project? Should they make decisions in areas such as WordCamps, documentation, or theme review? The lead developer role "didn't really have a set of responsibilities assigned with it or expectations,” says Matt. According to him, the lead developer leads development, not other areas of the project; he believes that confering authority and responsibility to a development role makes it difficult for non-coders to achieve project authority and responsibility.

Matt had articulated as much, as early as 2005, in stating that commit access did not equate to community status. It may never have been Matt’s intention to automatically confer authority on people with commit access, though extending commit demonstrated that committers had earned trust, and, as such, people naturally looked to committers as community and code leaders. Since roles and responsibilities were undefined, people simply perceived commit access as a general leadership role. The only non-coder who had an official leadership role in the project -- other than the lead developers -- was Jen, but she was an integral part of the core development team and there was no clear path for anyone to follow in her footsteps. In June 2012, the confusion around the role brought conflict. Since WordPress 3.0, a new generation of coders had driven development. Contributor changes were marked between the 2010 core meetup in Orlando, Florida, and the 2011 meetup in Tybee Island, Georgia. In 2010, just the small team of lead developers (Mark Jaquith, Andrew Ozz, Peter Westwood, Matt, and Ryan Boren along with Jen) met up. In 2011, the meetup had new faces including Dion Hulse, Jon Cave (duck_), Daryl Koopersmith, and Andrew Nacin.

From time to time, someone arrives and influences the project. In the early days, Ryan Boren drove WordPress' development, but post-WordPress 3.0, it was Andrew Nacin. "Nacin like Ryan is one of those guys that just has an ability to get in a flow, and just really crank and get focused intensely, and get through a ton of work," says Matt.

Nacin’s project influence grew, and between WordPress 3.4 and 3.5, Ryan Boren proposed that since Nacin drove releases strongly, he deserved recognition and should be made a lead developer.

Rather than appoint Nacin as a lead developer immediately, Matt proposed an organizational shift in the project. Matt argued that the lead developer title was historical and non-meritocratic, that those driving the project should hold leadership roles. Matt wanted opportunities for new developers to assume project leadership roles. He proposed that, instead of having a small group of lead developers, the project move to release leads, nominating Andrew Nacin and Daryl Koopersmith to assume the role in the next release. Matt's proposal offered clear authority to individuals for a given release; release leads would have final say, both over the lead developers, and over Matt. Some in the "historical and un-meritocratic" roles perceived this move as an attempt to remove the old guard to make way for the new. While a number of the lead developers aren’t active in core on a daily basis, they are in regular contact with those who work on core, providing advice on architecture and development.

On reflection, Matt says that there was a misunderstanding. He didn't mean to imply that the people holding lead developer roles were worthless or irrelevant, but that the roles did not reflect project reality. "A source of some of the conflict," says Matt, "is this idea that the lead developers sort of had the same role as me where they had sort of purview over everything across all parts of WordPress."

The lead developer role discussion raised dissatisfaction around project decision making. Many of those who ran day-to-day development felt that unilateral decisions were made without team consultation. Matt had taken a less active role in recent years, as Jen and Ryan, supported by the other lead developers, drove the project, yet decisions were made and announced without consultation. This was a culmination of other issues within the core development team and in the wider project: checking in code without consultation, providing feedback only toward the end of a release, and decisions around WordPress.org -- the site Matt owns, but that influences the entire community. In response, some core team members -- including lead developers and other team members -- sent a group email to Matt to express their discontent with the project. They felt that Matt’s perspective on the project's organization, authority, and responsibility, didn’t reflect the project's realities. The group proposed an official project leadership team; they wanted to retain the lead developer title as a meritocratic title for core developers who aligned with WordPress' philosophies, demonstrated leadership, code expertise, and mentored new developers. While the group happily supported the release leads proposal, they felt that the decisions for architecture, code, and implementation should rest with the lead developers, and that decisions affecting the project should lie with a leadership team. In response, those involved scheduled a Google Hangout to discuss the issues, air grievances, and find a way forward. As a result, things changed, and the first 3.5 release cycle post reflects some of those changes.

Andrew Nacin was promoted to lead developer, and core development adopted release leads with responsibility for an individual release cycle. They chose media as the scope for the 3.5 release; the development team had wanted to tackle it for some time, but with such a large scope, it hadn't been attempted. Daryl Koopersmith created a plugin, called Mosaic, which was the prototype for new media management. Much of it was written in JavaScript, where Daryl's expertise lay. But as a PHP free software project, there were few who could help him. As a result, Andrew and Daryl spent between 80 - 100 hours a week working on the release.

While the release itself was well received and media was overhauled, the actual development cycle wasn't such a success. It was a huge amount of work, involving lots of feedback, codebase iterations, and coding a whole new feature from scratch. There were four major iterations to the user interface, including one 72 hours before the release. This meant that the new "release leads approach" got off to a faltering start. The intent was to have release leads guide and lead a release, not necessarily spend hours carrying out heroic coding feats. Once again, the release cycle focused on a single feature; it shipped because two coders broke their backs getting it done. But the next release cycle -- 3.6 -- revealed that the release-specific feature development model was broken.

41. The Community Summit

The first en-masse, invitation-only WordPress community get-together -- The Community Summit -- took place in 2012. The Community Summit focused on issues facing WordPress software development and the wider WordPress community. Community members nominated themselves and others to receive an invitation; a team of 18 people reviewed and voted on who would be invited. The attendees -- active contributors, bloggers, plugin and theme developers, and business owners from across the WordPress community -- came to Tybee Island, Georgia, to talk about WordPress.

The main event, held at Tybee wedding chapel, was a one-day unconference. A few informal days for project work were scheduled afterward. In the morning, attendees pitched suggestions for discussion, discussion groups formed around tables, and twice during the day, individual groups shared their proposals for taking action.

The subjects discussed covered the spectrum of development and community issues. Development-specific topics included mobile apps, improving deployments, using WordPress as a framework, multisite, JavaScript, the theme customizer, and automatic updates. They talked about how to deepen developer experience, including better information for developers on UI practices. Broader community discussions focused on the role of the WordPress Foundation, open sourcing WordCamp.org, the GPL, and women in the WordPress community. There were discussions about different WordPress.org teams, such as UI, accessibility, theme review, and about improving documentation. Summit participants came from around the world; attendees talked about internationalization and global communities. Business owners raised issues such as managed WordPress hosting and quality control in commercial plugins. Finally, there were discussions about making it easier for both individuals and businesses to contribute to the project.

With so much discussion, many different ideas surfaced. Some proposed ideas moved forward, while others languished lacking contributor support. Summit discussions resulted in:

- Better theme review process documentation to increase consistency and transparency.

- A documentation and Codex roadmap (developer.wordpress.org eventually launched).

- Language packs included in core in WordPress 4.0.

- Headers added to the P2 themes to instruct contributors on how to get involved.

- Published a make/events sub-team list.

- Automatic updates for core.

- Individual plugin reviews on WordPress.org.

- Open sourced the WordCamp.org base theme.

As well as creating a space for contributors to discuss issues, many contributors met for the first time at the summit, and the in-person talks invigorated the community.

A new team -- a plugin repository review team -- formed. Up until then, Mark Riley carried the load reviewing plugins for the repository. The community believed plugins required the same rigor as themes. Plugin code quality was raised on community blogs and on wp-hackers. Otto started to review plugins too, and later Mika Epstein (ipstenu) and Pippin Williamson (mordauk) helped conduct plugin reviews. Later, Boone Gorges (boonebgorges) and Scott Riley (coffee2code) joined the team.

The plugin review team faces different challenges than the theme review team. A theme is a specific group of template files with a defined structure. It calls functions, it requires a header, footer, and a sidebar. A plugin can be anything at all, so there’s no way to automate reviews, which can be a lot of work. This review process cleared out malicious plugins, spam plugins, and plugins with security holes. A set of guidelines evolved to protect WordPress users.

Again, a small group of contributors created a team to address a specific project need. This has continued ever since the summit; a team develops training programs for people who want to teach WordPress, a team moderates WordPress.tv, and there's a team of contributors who help to support meetups. The summit allowed people to get together, to talk about their own interests, meet like-minded contributors, and move projects forward. The community got to be together as a community, to get to know one another socially -- instead of through text-based, online communication.

42. The Spirit of the GPL

By early 2013, the GPL discussion had slowed. Not everyone liked it, but most accepted that the WordPress project would only support 100% GPL products. Many were surprised by a sudden flare-up around not just GPL legalities, but the “spirit” of the license. In a 2008 interview, Jeff Chandler asked Matt about the spirit of the GPL. Matt said that the spirit of the GPL is about user empowerment, about the four freedoms: to use, distribute, modify, and distribute modifications of the software. Software distributed with these four freedoms is in the spirit of the GPL. WordPress was created and distributed in this spirit, giving users full freedom.

The Software Freedom Law Center's opinion gives developers a loophole around themes -- one that helps them achieve GPL compliance -- but denies the same freedoms as WordPress. PHP in themes must be GPL, but the CSS, images, and JavaScript do not have to be GPL. This is how Thesis released with a split license -- the PHP was GPL; the remaining code and files were proprietary. This split license ensures GPL-compliance, but does not embrace the GPL's driving user-freedom ethos.

The loophole may have kept theme sellers GPL-compliant, but WordPress.org rejected that approach. In a 2010 interview, Matt said “in the philosophy there are no loopholes: you’re either following the principles of it or you’re not, regardless of what the specific license of the language is." WordPress supports theme sellers that sell themes with a 100% GPL license. Those who aren’t 100% GPL receive no promotion on WordPress.org or on official resources.

In early 2013, ThemeForest -- Envato's theme marketplace -- came under scrutiny. Envato runs blogs and marketplaces that sell everything from WordPress themes and plugins, themes for other CMSs, to photographs, videos, and illustrations. WordPress is just one aspect of their business, though a significant one, and ever-growing. Envato became GPL-compliant in 2009 by releasing their themes with two licenses: GPL for the PHP, and a proprietary license for the remaining files and code.

ThemeForest has long been a popular choice for individual theme sellers. It offers exposure and access to a huge user community. As the theme shop marketplace saturated, it became more and more difficult for new theme sellers to break through.

Theme shops like StudioPress, WooThemes, and Elegant Themes dominate the market. ThemeForest offers everything a theme seller needs: hosting, sales tools, ecommerce, and a shop front. People can sell themes without the set-up work that can steal so much time. Theme sellers make good money out of selling on ThemeForest. As early as December 2011, Envato announced its first theme seller to make a million dollars in theme sales.

In January 2013, ThemeForest author Jake Caputo received an email from Andrea Middleton (andreamiddleton) at WordCamp Central. He was told that, as a ThemeForest author, he was not allowed to participate at official WordPress events. Jake had already spoken at two WordCamps, had plans to speak at a third, and was helping to organize WordCamp Chicago.

The issue was over theme licensing and WordCamp's guidelines. WordCamps are official WordPress events that come with the WordPress Foundation's seal of approval. Organizers, volunteers, and speakers must fully embrace the GPL -- going beyond GPL compliance to pass on all WordPress' freedoms to users. The guidelines state that organizers, volunteers, and speakers must:

Embrace the WordPress license. If distributing WordPress-derivative works (themes, plugins, WP distros), any person or business should give their users the same freedoms that WordPress itself provides. Note: this is one step above simple compliance, which requires PHP code to be GPL/compatible but allows proprietary licenses for JavaScript, CSS, and images. 100% GPL or compatible is required for promotion at WordCamps when WordPress-derivative works are involved, the same guidelines we follow on WordPress.org.

ThemeForest vendors had only the split license, in which the PHP was GPL and the CSS, JavaScript, and images fell under a proprietary license. For Jake to become 100% GPL, he would have to stop selling on ThemeForest and find a new outlet for his themes. This meant losing access to the more than two million ThemeForest members -- not to mention a significant portion of his income.

WordCamp Central's actions angered some community members; some thought it was unfair to ask theme sellers to give up their livelihood simply to speak at a WordCamp. Others supported WordPress.org; they believed the stance consistent with the GPL.

On both sides, people were frustrated for ThemeForest's authors. While the issue had little influence on the powers-that-be at WordPress or Envato, theme authors stuck in the middle suffered. With only the split license at Themeforest, they had one choice -- jeopardize their short-term livelihood by moving off ThemeForest.

The argument raged in the comments of Jake's blog, spiralling to other WordPress community blogs, and to the ThemeForest forums. Matt joined the discussion on Jake's blog, saying that if ThemeForest authors had a choice about licensing and could release their theme under the GPL, then "Envato would still be breaking the guideline, but Jake wouldn't, so it'd be fine for Jake to be involved with WordCamps."

Collis Ta'eed, CEO of Envato, responded on WP Daily, fn-1 outlining Envato's licensing model rationale. As a designer, Collis' main concern is protecting his designers' rights, while ensuring that customers can use the resources they purchase.

As with so many disagreements in the WordPress community, it came down to a difference in emphasis. While the WordPress project emphasizes user freedoms, Envato emphasizes creators' rights. Both felt strongly that they had the moral imperative, and backing down meant violating the principles that underpinned their organization. The WordPress project places user freedoms over and above every thing else. If this meant excluding theme authors who sold on ThemeForest, then so be it.

Collis, on the other hand, wanted to make sure that theme authors felt confident that their themes were safe from piracy. He was also worried about having a GPL option for authors. He wrote, "I worry that external pressures will force an increasing number of our authors to change their license choice, some happily, some not." Having just one (split) license meant that authors wouldn't be forced into that situation.

From the project’s perspective, theme authors could choose to sell their themes on ThemeForest, or sell their themes under the WordPress community's ethos (and thus speak at WordCamps). In a podcast on WP Candy, Jake said he didn't feel he had a choice about where to sell his themes. ThemeForest had become such an important part of his income that he would have to forfeit that income if he moved elsewhere. After the podcast, Collis wrote a second post on WP Daily, in which he said:

I think I've been wrong in my stance. I would like to change that stance, and feel that ThemeForest should offer an option for authors, if they choose, to sell their themes with a GPL license covering the entirety of the theme.

Collis surveyed ThemeForest authors to gauge support for a GPL opt-in option. "I felt pretty guilty that our authors were paying some sort of price for selling with us, that felt pretty wrong," says Collis. The results showed that verified authors were split; some said they would license their themes under the GPL, the same number said they would stick with the split license, and 35% said that they didn't know which license they'd choose. On March 26, Collis announced a 100%-GPL license for ThemeForest authors. Jake was once again allowed to speak at WordCamps.

43. The Problem with Post Formats

The 3.6 release cycle was challenging; it precipitated a new approach to the development process. Two core WordPress philosophies, design for the majority and again, deadlines are not arbitrary, were tested. The 3.6 release cycle process followed the cycle started in WordPress 3.4: there was a unified theme for the release -- this time content editing. Small teams worked on key features. Some features need more research and development than can be achieved within a single development cycle, and the WordPress 3.6 cycle surfaced this flaw.

Post formats were 3.6's headline feature. Introduced in WordPress 3.1., post formats allow theme developers to lend a unique visual treatment to specific post types.

Post formats lacked a standard user interface. In WordPress 3.6, release leads Mark Jaquith and Aaron Campbell tackled the problem. The release cycle had different stages: in the scoping chat, the release lead decided on the release's key features, created teams, and assigned feature leads. Feature leads ran their teams. The release leads coordinated with the teams and made the final decision on what made the release.

Carrying out major user interface changes in just a few months is challenging, at best. WordPress 3.5 demonstrated that to meet the deadline, the release leads needed to put in heroic coding efforts.

The 3.6 release encountered problems; features were dropped as contributors discovered they'd overcommitted themselves. The biggest issue was around the post formats user interface, inspired by Alex King’s Post Format Admin UI. Much thought and study went into the post formats UI. Which UI would offer users a logical, intuitive workflow, without adding needless complexity to the UI or the experience?

The problem was that despite time spent on wireframes and development, the team ended up unimpressed. They created specifications, built to the specifications, and were unhappy with the result. “It's like ordering something from the restaurant that sounds great,” says Aaron Campbell, “but as soon as it sits in front of you and you smell it, it's like, 'Ahh, definitely not what I was in the mood for.'" Even during WordPress 3.6's beta period, community members experimented with better approaches to the problem.

<img src="/wp-book/images/44/post-formats.jpg" "one of the proposals for the post formats UI" />

The post formats user interface

April 29 was WordPress 3.6's target release date. On April 23, Jen -- who had by that point stepped back from her involvement in development -- said that post formats weren't ready. She said that the user interface was confusing, underscoring WordPress' deadlines are not arbitrary philosophy. The thread, in addition to highlighting the post formats UI flaws, showed that not everyone supported deadlines are not arbitrary. Ryan Boren wrote:

The four month deadline is so fanciful as to be arbitrary. It always has been. Historically, we just can’t do a major release with a marquee UI feature in that time, certainly not without heroic efforts of the 3.5 sort. So we end up facing decisions like this. Every single release we wonder if we have to punt the marquee feature. Punting often requires major surgery that can be as much work as finishing the feature. Punting is demoralizing. Four month releases are empty promises that bring us here.

In the end, Mark and Aaron pulled post formats. A lot of work had to go in to removing it from core; the release was heavily delayed, finally appearing on August 1, 2013 -- three months after the intended release date. The team promised to turn the post formats feature into a plugin, but the plugin never materialized.

Again, a user-facing feature held up a WordPress release. Because features were tied to the development cycle, it meant that the release cycle's duration restricted and compromised UI features and/or major architectural changes. Just like tagging before it, post formats was a problem too complex to solve in a few short months. It isn’t always easy to make interface decisions. It’s harder to iterate on design than on code.

When the release deadline approaches and a feature isn't ready, the development team rushes to try to get it finished. The release is delayed by a week, and then by another week, and in some extreme cases, as was the case with WordPress 3.6, the release is delayed by months. By that point, it becomes impossible to give a firm date for when a release will happen. And the process becomes more complicated as the release lead oscillates between trying to improve a feature and deciding to pull it. Up until 3.6, there was no contingency plan built into the development process that allowed for these challenges in designing a user-facing UI.

The solution to this problem was available, and always had been available, within WordPress’ infrastructure. Twice before, core user features had been pulled from plugins into core -- widgets and menus. Widgets had been built for the WordPress.com audience, turned into a plugin, and brought in to core. Menus had stumped the core development team and they solved that problem with a plugin. In both these cases, feature design and testing happened long before approaching core. And as the WordPress 3.6 cycle dragged on, a small group of designers worked on a new WordPress feature in a plugin: it was a project called MP6. The project would be the flagship for a new approach to development that had a lasting influence on how WordPress features were developed.

44. MP6

By 2013, WordPress' admin had seen little change since the Crazyhorse redesign in 2008. Change happened in 2013, though it didn’t only result in a new look for WordPress. WordPress feature development changed, introducing a new approach in which feature design, feedback, and iteration used a plugin that was eventually merged with core.

In January 2013, Ben Dunkle proposed new, flat icons. The WordPress admin was outdated, particularly on retina displays where the icons pixelated. Flat icons would scale properly and also allow designers to color icons using CSS. Andrew Ozz checked in the changes.

The changes kicked off huge discussions about icons, a new trac ticket, and a long discussion on the UI P2. People were divided on the icons. Some liked them, but felt that they didn't fit WordPress' admin design; modern icons only emphasized how dated the rest of the admin had become. Consensus didn't materialize. Mark, who was release lead at the time, decided not to put the changes in WordPress 3.6. Instead, designers interested in redesigning the admin could iterate on the design in a plugin called MP6.

Matt Miklic (MT), the designer who had put the original coat of paint on Crazyhorse, helmed MP6. Via Skype, Matt asked MT and Ben Dunkle to reimagine WordPress' admin, consider how a redesign could work, and set parameters. MT believed that they ought to respect the research that informed Crazyhorse's UI. Instead of iterating the layout and functionality, they focused on an aesthetic refresh.

Both Matt and MT were keenly aware of the issues and challenges in each major WordPress admin redesign. They wanted MP6 to be different.

Shuttle, for example, had been cut off from the rest of the community, designed by a cloistered group of designers trading comps and slowly losing touch with "the client." No one person was responsible for Shuttle's overall vision; there was no accountability.

By contrast, the Happy Cog team looked at WordPress with a fresh set of eyes. Their distance allowed them to treat WordPress as a piece of software, not as an object of devotion. They stayed in touch with their client -- Matt -- but were removed from the community's thoughts and opinions. MP6 solicited feedback from all of the people with a stake in the project. That brought its own challenges -- whose feedback was the most legitimate? What should be integrated? When was someone just complaining for the sake of it?

Crazyhorse emphasized the importance of in-depth user testing. With all the testing on Crazyhorse, MT knew that he didn't want to carry out a structural overhaul, conduct extensive tests, and gather the data needed to prove improvement.

The MP6 project took a different approach. Like Shuttle, a group of designers worked alongside the free software project. Instead of a mailing list, they had a Skype channel so that they could talk in private, but anyone was allowed to join in. "Even though the group worked in private," says MT, "the door into the group we were working on was open, so if anyone said they were interested they could just walk in." This allowed people less comfortable with WordPress' chaotic bazaar to participate. Designers traded ideas and feedback -- without the danger of someone coming out of nowhere and tearing an idea down before it was even fully formed.

The MP6 project took advantage of WordPress’ plugin architecture; work took place on a plugin hosted on the WordPress plugin directory. Anyone could install the plugin and see the changes in their admin. Every week, the group shared a release and a report open to public feedback. This open process meant that community members could be involved on different levels. It also meant that the group could never steer too far off course. The core team was always aware of what was going on with MP6 and could provide feedback. More designers were involved than with Shuttle: the group grew to fifteen members. With MT as lead, they avoided the "too many cooks" problem. The designers and the community accepted that MT had the final say on the design.

The MP6 project was announced in March 2013. The design process began with MT playing around with the CSS. He started out with a unified, black, L-shaped bar around the top and the side of the admin screen: "the idea," he said, "was that the black would feel like a background and the white would feel like the sheet of paper lying on top of it, so it would unify these disparate things." Once MT assembled the basic visual, the contributors refined the design. These changes happened iteratively. The community saw a report and a new plugin release each week, on which they gave feedback.

Challenges arose. Google web fonts caused heated discussion. Web fonts are designed specifically for the web. They’re often hosted in a font repository. A designer uses a CSS declaration to connect to the repository and the font is delivered to a website or app. MP6 uses the Open Sans font, which means that the font in WordPress' admin screens is hosted on Google's servers. Whenever a user logs into their admin, Google serves the fonts. Some don't want to connect to Google from their website; this also causes problems for people in countries where Google is blocked. Bundling the fonts with WordPress, however, requires a huge amount of specialized work to ensure that they work across platforms, browsers, and in different languages. In the end, they decided to use Google web fonts. A plugin was created to allow users to shut them off.

Despite minor hitches, the MP6 project went smoothly. Joen Asmussen, who'd been a part of the Shuttle project eight years earlier said, "I would say that MP6 did everything right that Shuttle did wrong."

Over the eight years since the first attempt to redesign WordPress’ admin, WordPress had matured. When things are done behind closed doors, people feel disenfranchised, and yet the bazaar style model doesn’t suit every, single aspect of software development. It’s within this tension that a balance must be struck, with space for ideas to flourish.

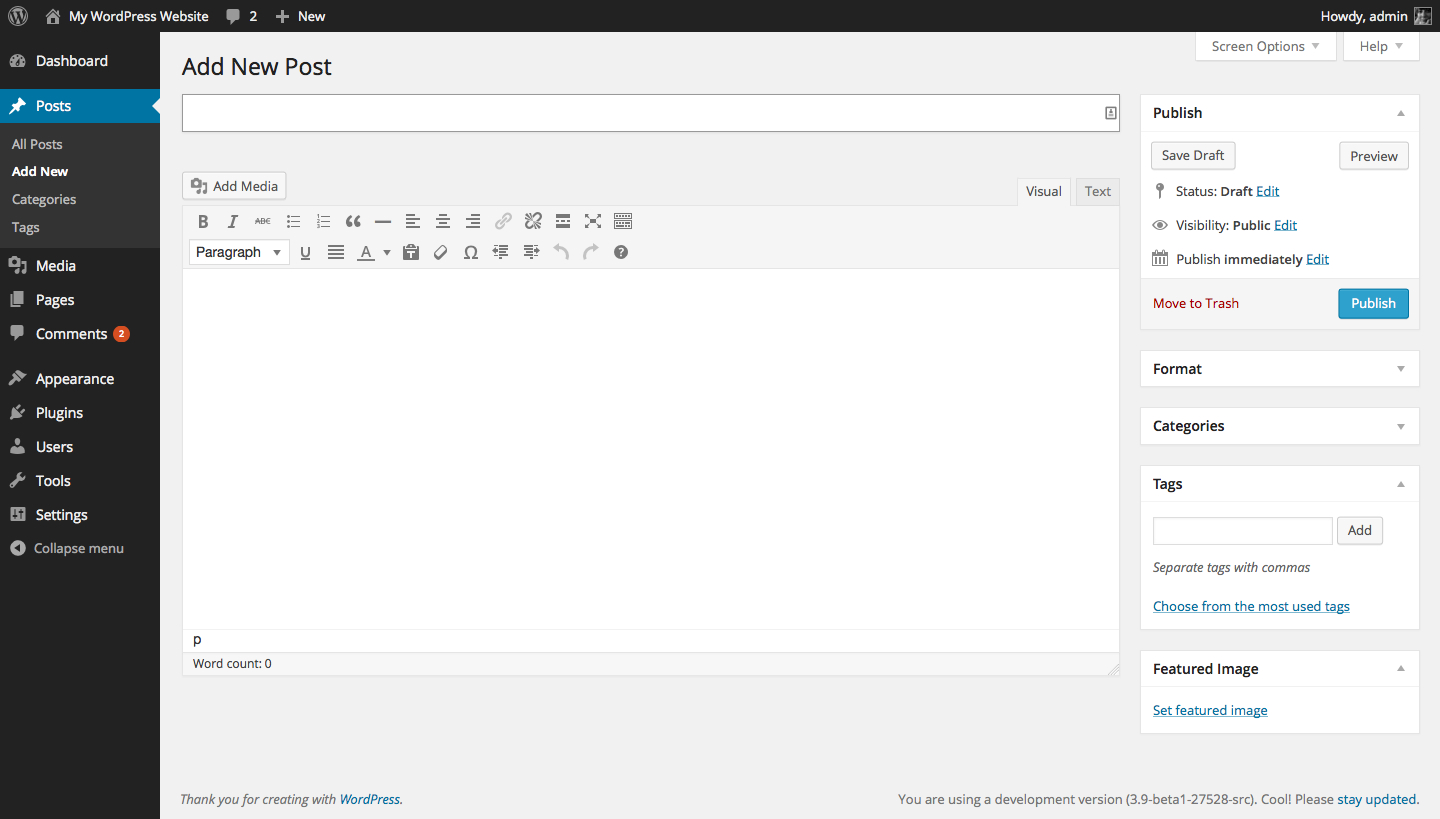

The MP6 plugin merged with WordPress 3.8, released in December 2013, demonstrating that, while it may take a while to get there, harmonious design in a free software project is possible.

The Write screen in the WordPress 3.8 admin.

All of this happened as 3.6 rumbled on. Development continued on the core product, MP6 development happened separately; it wasn’t constrained by WordPress' release timeline. MT and the designers iterated quickly; users installed the plugin to test it and offer feedback. This was a new process that hadn't been possible before. To test new features in the past, a user would have to run trunk. By developing the feature as a plugin, a community member could focus by helping with the sole plugin that they were interested in.

MP6 was proving to be a success, and in the summer of 2013, it was decided, for the first time, to develop two versions of WordPress simultaneously -- 3.7 and 3.8. WordPress 3.7 was a two-month, platform-focused, stability and security release lead by Andrew Nacin and John Cave. New features in 3.8 were developed as a plugin.

This “features as plugins” method* will allow teams to conceptualize, design, and fully develop features before landing them in core. This removes a lot of the risk of a particular feature introducing uncertainty into a release (see also 3.6, 3.5, 3.4 …) and provides ample room for experimentation, testing, and failure. As we’ve seen with MP6, the autonomy given to a feature team can also allow for more rapid development. And in a way, 3.7 provides a bit of a buffer while we get this new process off the ground.

While the project prepared to merge MP6 as a plugin in WordPress 3.8, an opportunity arose to do automatic updates -- something that had been talked of within the project for years. Automatic updates had long been a goal, previously unachievable. Automatic updates needed the proper code structure to be in place on WordPress.org, as well as community trust. Community members needed to be okay with WordPress changing their site automatically.

WordPress has collected data since WordPress 2.3 that allows WordPress.org to create personalized automatic updates. WordPress uses the data to make sure that a site receives an update compatible with its PHP version and site settings. In the few failure cases, the user gets an error message with an email address that they can use to email the core developers who will fix their website. As of late 2014, automatic updates are for point releases only. So while major releases of WordPress are not automatic (3.7, 3.8, etc.) point releases are (3.7.1, 3.8.1, for example). This means that security updates and bug fixes can easily be pushed out to all WordPress users.

Within the space of just two short releases -- 3.7 and 3.8 -- big changes transformed the software and the development process. Automatic updates mean that WordPress users are safer than ever. WordPress 3.8 saw the first release in which a feature developed as a plugin merged with core. This finally decoupled core development from feature development. So many past delays and setbacks happened because a feature held up a release. It gave developers more scope for experimentation and created safe spaces for contributors to get involved with core development. While the MP6 admin redesign was the first plugin integrated under this model, since then, feature-plugins have brought in a widget customizer, a new theme experience, and widget functionality changes. Experiments are ongoing in image editing, front-end editing, user session management, and menus.

fn-1 WP Daily has since been acquired and its content moved to Torque magazine.